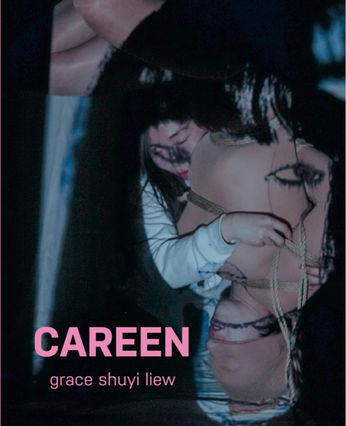

Careen by Grace Shuyi Liew

Paperback: 87 pgs

Publisher: Noemi Press (April 2, 2019)

Purchase @ Noemi Press

Review by Len Lawson.

Grace Shuyi Liew writes a compelling hybrid of poetry and memoir in her debut full-length collection Careen. The intensity of her language dashes through three segments, streaking through themes of mortality, emotional distress, and the disconnect among body, soul, and spirit.

The opening poem “What Does It Mean to Be Durational, Not Eternal?” displays graphic imagery of perverse intimacy. Liew shows in this prelude the depths with which humanity can sink into depravity, leading to bodies bowling into one another without untainted connection. The opening lines depict the spiral: “In this state, my opacity blooms/like wrong/soap… White foam coats/my dreams/of fascism, alien abductions, and anywhere/but home”. The color white becomes perverse unlike its purity in most literature. The structure of the poem then becomes fragmented into shorter, indented lines of verse. Liew continues with the spiral through the lens of sexual encounters. “I can’t be loud/when Asian porn is still/a consumer category,/milk-white skin like/a reverse oil spill” (Lines 35-39). Whiteness has become darkness in the flesh of Asian women seen as commodities. The speaker herself takes on the perverse intimacy:

…I reenact rape fairytales

with white lovers, all of whom

insist on hating Trump

while they fuck me—their rage

about The Administration dignifies

into a hard-on slinging

for my civic rights. Why so angry?

I ask. Blowjobs don’t cost much

more than falling

in love with anyone

who expresses outrage on my behalf--

always when I lift my shirt to reveal

my private galaxy of

bruises

they all cum immediately” (Lines 118-132)

The political, raging rapists exist as the dregs of this abyss where the speaker has fallen. They take out their anger on the speaker who reveals her most vulnerable parts to them for their gratuitous pleasure. This is not real intimacy. The poem ends with an anecdote of a girl jumping from a cliff when those trying to encourage her not to jump say “think of your mother” giving the child “the/sincerity to finally push herself into thin air” (Line 142). The proverbial last lines ensue: “We learn bodily ire from our mothers—how to run/out of our own flesh—”. The alternative to establishing connection with humanity, even with one’s own mother, is choosing death with the soul attempting to leap from the body for relief. Liew shows here the bottom from where her narrative must climb or remain in this tragically intense opening poem.

In the first segment, Eventually Every Color Careens into Its Own Lack, Liew penetrates the displaced intimacy with various proverbs. She inquires “To the first man who penetrated the sound barrier:” with questions that analyze the state of matter in this distorted space of displacement. The proverbs begin with an acknowledgment of the new state of distorted intimacy and acceptance of it: “To have survived a life of gentle skirt-lifting is to never reap the joy of underexposure” (Line 74). This state does not forgive or excuse the contribution of colonization: “To collect hate colonialize first a chorus of white-bellied weeping./To colonialize is to replenish the gaping cavity that once held the guts of a whole generation” (Lines 80-81). More proverbs eulogize the displaced intimacy: “When translation fails, the displaced easily become worthless beings./But this idea of the barren abruptly baring all/of itself when alarmed by intimacy does not tidy up easy” (Lines 89-92). The hollow, barren environment in the anti-intimate displacement leaves the soul yearning for the comfort of connection within humanity.

The second segment, Outgrowth of Contingent Nations, details the emotional distress of the distorted intimacy and emotionless void in humanity. Liew speaks of “the body’s melancholia” in a state of “mimicry” to invoke love and self-care. The absence of closeness haunts the narrative: “You would really love to keep on living. You would/really love to forget the past (straighten out those bends in your yester-limbs)./The people you have _____ or ______ or _____ line up to ring your doorbell/with questions; their decoys walk right through the walls of your home” (Lines 11-14). Connection is like a ghost, and names cannot even be recalled. Bodies from the past line up to careen with us in this new state, yet this tangent in time persists without fail. The new state of being here identifies as feminine and reminds us that we can never return to the womb of love and connection.

“In this natural phenomenon: Specter of a small girl, half-beaming, splashing in a

green lake, her dark hair cropped at mid-cheek, her memory of her mother scant.

Inside you is a mother wounded from the death of her mother.

Inside her is a mother who never recovered from the birth of her children.

See how water parts for her” (Lines 63-68).

This tangent of displacement leaves us vulnerable, and when we grope for something other than ourselves here, we become faced with generational anguish from parental hosts who could not free themselves either. We are left only to encourage our hollow selves with “You are gonna be okay you say (closed in by bodies) (imaginary pangs) as you familiarize yourself with the facts of your dislocation. You were never clean…” (Lines 79-81).

In the third segment, Displaced, Replaced, Liew shows the displaced intimacy in various cities and locations. In “Berlin”, Liew applies the displaced theory to encountering Germans and the vexation of a new lip piercing. In “New York”, she exhibits the displacement while meeting old friends. In “(Between) Los Angeles & Other Coasts”, a dream state from being in the City of Angels overtakes the speaker. In “Kuala Lumpur”, capital of Liew’s home country Malaysia, a nostalgic tone reverberates in the city’s imagery. Returning home repeats the cycle of displacement or replacement of vacant emotion. “Your dreams are exposés that/allow no distance between yourself and every single felt emotion. Cross all the cities’ limits, get/out of bed, and repeat history. You will want yourself all over again, once you diminish the size/of your own warnings” (Lines 20-23).

Liew crafts a view into the world of the other with fear and trembling similar to the narrator of Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison. The stream of consciousness chills from scene to scene and dream state to dream state. Once readers are stripped of the status quo and forced to live this life of distorted intimacy, life in this collection feels desolate with nothing but the words of a gifted linguist to guide them through—but never out or free.

Grace Shuyi Liew is the author of Careen (Noemi Press, 2019).

Her work has appeared in West Branch, Black Warrior Review, Kenyon Review, cream city review, PANK, The Wanderer, and elsewhere. She is a Watering Hole fellow. Her other honors include the Lucille Clifton Poetry Fellowship from Squaw Valley Community of Writers, Aspen Summer Words scholarship, resident writer at Can Serrat in Barcelona, resident at Agora Affect, Vancouver Poetry House’s “10 Best Poems of 2016,” Ahsahta Press Chapbook Prize 2016, and others.

She holds a BA in Philosophy from Hamilton College, and MFA in Creative Writing from Northern Arizona University. She is a Contributing Editor for Waxwing.