Paperback: 102 pages

Publisher: University of Pittsburgh Press (Pitt Poetry Series), 2015

Purchase: @ Amazon.com

Review by Margaret Stawowy

Reading Ross Gay’s work is reason for exhilaration. In his third volume of poetry, he writes of gardens with their seasons of fruition, hibernation, loss, and rebirth. There is lightness and generosity in these pages, like a long-needed exhalation when spring comes after a long winter.

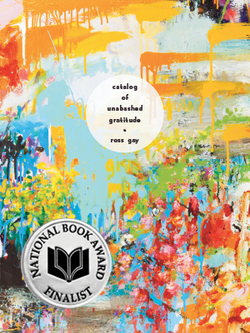

Ross Gay is a professor of English at Indiana University, Bloomington, as well as a poet and gardener. The cover art provides a hint of the tenor of work to be found within: riotous color, dripping next to impressionistic strokes of what could possibly be canna, stock, foxglove, and roses. This is a garden of unrestrained pigment that grabs the reader at the gate with an invitation to meander the paths within.

Gay’s poems are left-hand justified, often composed of one rambling rose of a sentence that blooms gracefully across the pages, some with punctuation, others without, like single and double-flowering varietals.

He opens with “To a Fig Tree on 9th and Christian” in Philadelphia, a city that doesn’t always deliver on the brotherly love aspect for which it is named, on a street that is Christian in more ways than one. This particular fig unites people in a rapturous Babette’s Feast-of-a-party, bringing neighbors and passersby together to partake of near mystical fruit from a

“. . .tree which everyone knows/cannot grow this far north.” Only it does. When Gay admits: “yes I am anthropormorphizing/goddamit I have twice/in the last thirty seconds/” that’s okay. We’re already under the spell of this sugar-abundant tree bent on seducing us into joining together in Eden under its leaves.

This kind of peaceable kingdom material could get old fast, but gardens are also about dirt, thorns, and decay. Gay pays attention to these details as well. In “burial” he balances death with the good-natured mischief of his departed father, who will not stand for piety or sanctity. Gay takes his father’s ashes and dumps them into holes dug for two bare-root plum trees. Right from the start, dad gives him a little ash up the nose to remind him that, even dead, he hasn’t lost his grit. When the first plums finally ripen:

“. . . my father/guffawed by kicking from the first bite/baskets of juice down my chin,/staining one of my two button-down shirts,/the salmon-colored silk one, hollering/there’s more of that!/”

His father makes further cameo appearances in poems such as “armpit” into which his young son sticks his nose, and “the opening” in which his father bears a bucket of hot wings to share with his son, “comrade in spice and grease and gore.”

Besides the appearance of his father, “the opening” features a disembodied narrator who refers to himself in the third person as “Myself” with a capital “M.” Myself struggles with grief, temporality, and the uncomfortable, sometimes violent emotions that are precipitated by loss. The “opening” referred to in this poem is achieved with a pair of pruning shears, cutting back extraneous growth in a peach tree, so that the narrator can perch on its furthest branch to achieve an unobstructed view—to see and hear to the beginning of the poem--a KFC parking lot in Levittown, Pennsylavania, where a father buys an illicitly greasy treat to share with his son.

Gay pens odes and elegies to all manner of unexpected subjects including “ode to the puritan in me,” in which the narrator reveals that “he reads poetry/the puritan in me/with an X-Acto knife in his calloused hand/if not a stick of dynamite.” And that “the brim of whose/hat is so sharp/it could cut/ your tongue out.” This “puritan” feels the need to punish himself for “unpunishable” deeds, such as sneaking in the night behind the sleeping house to make of his body “a flower-dappled tree.” In other words, for not being a good puritan after all. No surprise.

Words like “joy” and “gratitude” can be found in these poems, words difficult to place on the page, like brush strokes of shocking pink and neon green. But then, he also uses words like armpit, goddammit, and whoopee. Gay earns penning rights to each and every word in this poetic seed catalog that demonstrates his ability to imagine and find renewal.

Publisher: University of Pittsburgh Press (Pitt Poetry Series), 2015

Purchase: @ Amazon.com

Review by Margaret Stawowy

Reading Ross Gay’s work is reason for exhilaration. In his third volume of poetry, he writes of gardens with their seasons of fruition, hibernation, loss, and rebirth. There is lightness and generosity in these pages, like a long-needed exhalation when spring comes after a long winter.

Ross Gay is a professor of English at Indiana University, Bloomington, as well as a poet and gardener. The cover art provides a hint of the tenor of work to be found within: riotous color, dripping next to impressionistic strokes of what could possibly be canna, stock, foxglove, and roses. This is a garden of unrestrained pigment that grabs the reader at the gate with an invitation to meander the paths within.

Gay’s poems are left-hand justified, often composed of one rambling rose of a sentence that blooms gracefully across the pages, some with punctuation, others without, like single and double-flowering varietals.

He opens with “To a Fig Tree on 9th and Christian” in Philadelphia, a city that doesn’t always deliver on the brotherly love aspect for which it is named, on a street that is Christian in more ways than one. This particular fig unites people in a rapturous Babette’s Feast-of-a-party, bringing neighbors and passersby together to partake of near mystical fruit from a

“. . .tree which everyone knows/cannot grow this far north.” Only it does. When Gay admits: “yes I am anthropormorphizing/goddamit I have twice/in the last thirty seconds/” that’s okay. We’re already under the spell of this sugar-abundant tree bent on seducing us into joining together in Eden under its leaves.

This kind of peaceable kingdom material could get old fast, but gardens are also about dirt, thorns, and decay. Gay pays attention to these details as well. In “burial” he balances death with the good-natured mischief of his departed father, who will not stand for piety or sanctity. Gay takes his father’s ashes and dumps them into holes dug for two bare-root plum trees. Right from the start, dad gives him a little ash up the nose to remind him that, even dead, he hasn’t lost his grit. When the first plums finally ripen:

“. . . my father/guffawed by kicking from the first bite/baskets of juice down my chin,/staining one of my two button-down shirts,/the salmon-colored silk one, hollering/there’s more of that!/”

His father makes further cameo appearances in poems such as “armpit” into which his young son sticks his nose, and “the opening” in which his father bears a bucket of hot wings to share with his son, “comrade in spice and grease and gore.”

Besides the appearance of his father, “the opening” features a disembodied narrator who refers to himself in the third person as “Myself” with a capital “M.” Myself struggles with grief, temporality, and the uncomfortable, sometimes violent emotions that are precipitated by loss. The “opening” referred to in this poem is achieved with a pair of pruning shears, cutting back extraneous growth in a peach tree, so that the narrator can perch on its furthest branch to achieve an unobstructed view—to see and hear to the beginning of the poem--a KFC parking lot in Levittown, Pennsylavania, where a father buys an illicitly greasy treat to share with his son.

Gay pens odes and elegies to all manner of unexpected subjects including “ode to the puritan in me,” in which the narrator reveals that “he reads poetry/the puritan in me/with an X-Acto knife in his calloused hand/if not a stick of dynamite.” And that “the brim of whose/hat is so sharp/it could cut/ your tongue out.” This “puritan” feels the need to punish himself for “unpunishable” deeds, such as sneaking in the night behind the sleeping house to make of his body “a flower-dappled tree.” In other words, for not being a good puritan after all. No surprise.

Words like “joy” and “gratitude” can be found in these poems, words difficult to place on the page, like brush strokes of shocking pink and neon green. But then, he also uses words like armpit, goddammit, and whoopee. Gay earns penning rights to each and every word in this poetic seed catalog that demonstrates his ability to imagine and find renewal.

ROSS GAY is the author of three books: Against Which; Bringing the Shovel Down; and Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude, winner of the 2015 National Book Critics Circle Award and the 2016 Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award. Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude was also a finalist for the 2015 National Book Award in Poetry and nominated for an NAACP Image Award. Ross is the co-author, with Aimee Nezhukumatathil, of the chapbook "Lace and Pyrite: Letters from Two Gardens," in addition to being co-author, with Richard Wehrenberg, Jr., of the chapbook, "River." He is a founding editor, with Karissa Chen and Patrick Rosal, of the online sports magazine Some Call it Ballin', in addition to being an editor with the chapbook presses Q Avenue and Ledge Mule Press. Ross is a founding board member of the Bloomington Community Orchard, a non-profit, free-fruit-for-all food justice and joy project. He has received fellowships from Cave Canem, the Bread Loaf Writer's Conference, and the Guggenheim Foundation. Ross teaches at Indiana University.