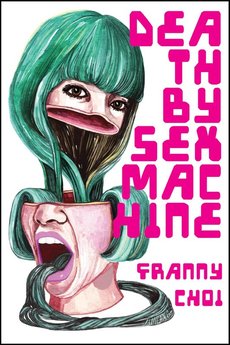

Death By Sex Machine by Franny Choi

Paperback: 48 pgs.

Publisher: Sibling Rivalry Press (2017)

Purchase: @ Sibling Rivalry Press

Review by Kaiya Gordon.

“I propose that we look at violence as a force that not only ‘ inflicts injury’ [...] but also produces identity in a realm of media entertainment where destruction is particularly enmeshed in the making of a new subject, the cyborg,” writes Anne Allison in “Cyborg Violence: Bursting Borders and Bodies with Queer Machines.” Cyborgs, Allison implies, are therefore not static beings, but organisms which “confuse prior identity borders [...] marked by both a dislocation and re-aggregation of bodies and body parts...” (242). Dynamically disturbing and rearranging the world around them simply by being, cyborgs are compelling because they are able to engage intersecting lived experiences without prescribing definitive or exclusionary truths.

Written language, on the other hand, is tied up in prescriptive forces. It’s impossible to write without dragging in old contexts and canons; without attempts at communication being warped by lived experiences and learned biases of readers. So I’m a sucker for cyborg theory––for anything that grapples with our human mess of articulation. And Death by Sex Machine, Franny Choi’s 2017 chapbook, grapples. I read Death by Sex Machine cocooned by covers, trying to block out the Columbus cold as best as I could. In my darkened bedroom, quieted by the still air outside, Choi’s poems bloomed new linguistic and creative possibilities. It’s an ambitious project which announces its ambition immediately; after the table of contents (here, in another nod towards imagined tech, called “directory”), Choi provides three quotes, taken, respectively, from Ex Machina, Chobits, and the author’s twitter feed. Each wrestles with the intersections between communication, technological barriers, gender, and race. Though named, the speakers are un-described, only existing through the words Choi brings to the page. By presenting the quotes as such, with no introduction or context, Choi immediately thrusts the reader into the soundscape of Death by Sex Machine, in which poems contain multiple contradicting voices, of varied volumes, paces, and tones.

Choi, like Allison, treats the cyborgs in her work as dynamic beings, adapting and re-adapting in each poem. But unlike Allison and other cyborg theorists, Choi’s cyborgs struggle with language. In the book’s opening poem, “Turing Test,” the title of which is taken from Alan Turing’s 1950 test developed to determine whether machines exhibited human consciousness, Choi’s narrative voice leads the poem through a series of questions. “// do you understand what I am saying” the poem asks. And when it answers itself, it does so by developing poetic rules which inform the tone of the poem. Yes, the poem answers itself, “we stayed up / practicing / girl / girl / girl / til our gums softened / yes / i can speak / your language / i broke in that horse / myself” (8). The poem emphasizes the work and choices necessary to learning (or “breaking in”) a language. And throughout the book, language is adapted for various uses and consciousnesses. What, for example, is the meaning of “ghost” relevant to Death by Sex Machine? Of mouth? “Glossary of Terms,” one of the more formally experimental poems of the book, presents the reader with a grid of various words, their meanings, synonyms, antonyms, origins, and dreams. At first glance, the poem might look like a gimmick––but in reference to the rest of the book, it asks a valuable question about cross-community communication. If we are to test machines for “human” consciousness, as the first poem suggests, is it not necessary to adapt the language of that test to the needs of the machine?

By renegotiating language, both through poetic form and contextual meaning, Choi constructs a communication that is relative to need, so that there is always a relationship between a concept and its creation. Likewise, the form used in each poem to hold the concept informs how the poem is read––thus directly contributing to its meaning. In “Gendered Technologies and Cyborg Writing,” by Sara Louise Muhr and Alf Rehn, Muhr and Rehn note that what is “interesting” about canonical cyborg theory is that “technology itself is relegated to play at best a supporting role.” But, Muhr and Rehn argue, “we need to be better at discussing the often complex gender politics at play in our technologies of writing and publishing” (133). Reading Death by Sex Machine, I think: is every way we engage with the world not a technology? Aren’t the adaptions we each make to stay safe under constructed systems of power technologically profound?

Cyborg theory fails when it focuses entirely on the constructed nature of identity, rather than examining the power systems which necessitate that construction. But by turning poems into a cyborg technology, Choi gives herself and the reader space to focus on the choices made by persons who are “machin-ed” by social systems; that is, persons whose societal usefulness is determined entirely by the identities which also make them most vulnerable. In “Turing Test_Love,” the poet draws attention to the radical possibilities of language. “// so, how do you like working with humans,” the narrative voice asks, to which the poem responds: “if they used it against you / it is yours / to make sing” (37). The answer mimics the poems themselves; by creating poems both aware of and in response to limitations, Choi reclaims poetic tools as technology for resistance.

And what of the sex in Death by Sex Machine? In contrast to the movies and media that Choi writes against, Choi’s machines are, undeniably, able to digest and relate their experiences. It’s not that her machines are empowered, exactly (for who can empower those disenfranchised by the system without tearing the system itself down?), but that they are aware of and able to weaponize the orientalist gaze they face. In “G00dv1br@t1on$,” questions of origin are directly linked to the sexual possibilities of the poem, which in turn, inspire violence and fury. If, as cyborg theorists have implied, those gazing are only interested in the exterior of the sex machine, unwilling to engage with the construction beneath, then they are vulnerable to the machine’s aggression; blind to its weaponry because of a refusal to see beyond flesh.

Death by Sex Machine is encouraging and challenging work. In her invention of form, engagement with theory and genre, and truly empathetic approach to identity, Choi offers the reader a poetry of imagination; writing which builds new possibilities for itself, even as it remains relevant to contemporary conversations around poetry and body. It’s a brilliant read. Turning away from the book, I am renewed (though not soothed or restored!) in both my love for poetry and my ambition to capture and celebrate the gross complexities of conscious experience. But first: a Sci-Fi marathon. Bringing Choi to my TV, I hope, will make the stars a little more focused––the galaxies traveled a plane upon which to experiment with the technology of being.

Kaiya Gordon is a writer and poet from the SF Bay Area. They are a current university fellow at OSU and a reader at The Journal. Kaiya writes about local art and music for Audiofemme and The Bay Bridged, and has poems published by poets.org, Glass Poetry Journal, and 1001 Journal.