Read our interview with Jane Joritz-Nakagawa here.

Paperback: 28 pages

Publisher: Grey Book Press (2016)

Available @ www.greybookpress.com

Review by Margaret Stawowy

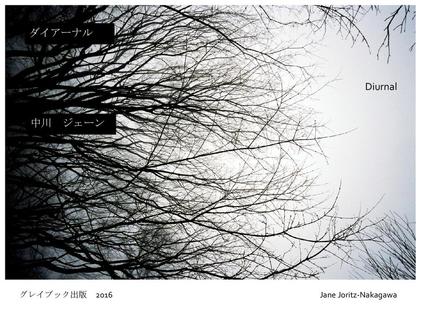

Heading into the shorter days of autumn and winter, Jane Joritz-Nakagawa’s chapbook, Diurnal, is the perfect poetry accompaniment. Published by Grey Book Press, the cover design by Trane DeVore features bare tree branches silhouetted against a stark sky. The poems in Diurnal are twenty-four in number, presumably one for each hour of the day—not a usual chronological day, but a day where time unhinges from linearity. Consider each poem to be a unit of poetic time, told in an invented sonnet form of seven couplets.

The lines of the couplets are short, generally two to three words and never more than six words. I’m almost tempted to start counting syllables. There is something reminiscent of haiku due to the minimal, yet suggestive language, where nothing is directly stated, but nonetheless imparted:

to translate the clouds

above ugly buildings

books on my body

strange amounts of granite

gradual shading

is nobody’s theory. . .

Jane Joritz-Nakagawa is a longtime resident of Japan and an English professor. Her academic interests include gender studies, history, eco-poetics, linguistics, and feminism, all topics that appear in her poetry, though the reader will intuit them rather than encounter them head-on. Adjacent lines levitate into the cerebral, then crash land into the visceral, as in (5):

bird’s furniture wires

my eyes maybe on backwards

I’d like it up the ass

another dismissal

scent of the dead

in the public of poetry

raping me blind

forgetting sparse oceans

shiny stupor

sorry descendants

in lackluster fields

moldy hospitals for souls

a botany of law

these visions such slippage

These are disquieting statements and images that speak to the normalization of degradation, violence, and apathy. Throughout Diurnal, there is specificity, but also a vagueness that is often noted as a linguistic quality of the Japanese language, a language at which Joritz-Nakagawa is fluent. The person responsible for the words or action is not called out. That’s up to the listener to intuit or supply. In part, it is this indirectness and vagueness that balances the poetry on well-sharpened edges.

There is also humor, lighthearted as well as dark, and visual and auditory details as seen in this excerpt from (23):

your face a shrine

your toe a morsel

our torso a shrapnel

our brain champagne

our ribs obtuse

our skull whiplash

their bones awhirl

there bones a world

A face being a shrine is a most Japanese allusion, as Shinto shrines are a fixture in many Japanese homes where food is placed for departed loved ones. Is Joritz-Nakagawa deconstructing the body in a playful Dem Bones manner (as in “the toe bone connected to the foot bone,” etc.)? Also, note the music created with words such as “morsel” and “torso,” “brain” and champagne,” as well as in the final couplet, “awhirl” and “a world.”

There is a heartbeat rhythm built into the meter, as carefree as a nursery rhyme--one of those slightly morbid ones that we love as children and fondly recall as adults.

This is Jane Joritz-Nakagawa’s fourteenth poetic work put out in the span of (take a breath) ten years! Obviously, she is deeply committed to poetry and writing, but not just her own. Joritz-Nakagawa has encouraged other English-language writers in Japan by founding The Japan Writers’ Conference (an annual event now overseen by fellow poets John Gribble and Bern Mulvey). She has also founded listserves to further encourage and connect with the work of English-language writers in Japan, especially ones living in more remote areas such as herself. Not to mention, she is a committed and well-regarded teacher in her field. What this preamble is leading to is an observation of how, over the years, she has found a voice and technique that reflects not only her ethics and commitment, but also her place in two cultures. Her work can be described as abstract and experimental, while also being satisfyingly, deeply somatic. The reader feels his or her way through the poetry more than anything else, and it is a result of the kind of literary alchemy that Joritz-Nakagawa has honed over time.

Paperback: 28 pages

Publisher: Grey Book Press (2016)

Available @ www.greybookpress.com

Review by Margaret Stawowy

Heading into the shorter days of autumn and winter, Jane Joritz-Nakagawa’s chapbook, Diurnal, is the perfect poetry accompaniment. Published by Grey Book Press, the cover design by Trane DeVore features bare tree branches silhouetted against a stark sky. The poems in Diurnal are twenty-four in number, presumably one for each hour of the day—not a usual chronological day, but a day where time unhinges from linearity. Consider each poem to be a unit of poetic time, told in an invented sonnet form of seven couplets.

The lines of the couplets are short, generally two to three words and never more than six words. I’m almost tempted to start counting syllables. There is something reminiscent of haiku due to the minimal, yet suggestive language, where nothing is directly stated, but nonetheless imparted:

to translate the clouds

above ugly buildings

books on my body

strange amounts of granite

gradual shading

is nobody’s theory. . .

Jane Joritz-Nakagawa is a longtime resident of Japan and an English professor. Her academic interests include gender studies, history, eco-poetics, linguistics, and feminism, all topics that appear in her poetry, though the reader will intuit them rather than encounter them head-on. Adjacent lines levitate into the cerebral, then crash land into the visceral, as in (5):

bird’s furniture wires

my eyes maybe on backwards

I’d like it up the ass

another dismissal

scent of the dead

in the public of poetry

raping me blind

forgetting sparse oceans

shiny stupor

sorry descendants

in lackluster fields

moldy hospitals for souls

a botany of law

these visions such slippage

These are disquieting statements and images that speak to the normalization of degradation, violence, and apathy. Throughout Diurnal, there is specificity, but also a vagueness that is often noted as a linguistic quality of the Japanese language, a language at which Joritz-Nakagawa is fluent. The person responsible for the words or action is not called out. That’s up to the listener to intuit or supply. In part, it is this indirectness and vagueness that balances the poetry on well-sharpened edges.

There is also humor, lighthearted as well as dark, and visual and auditory details as seen in this excerpt from (23):

your face a shrine

your toe a morsel

our torso a shrapnel

our brain champagne

our ribs obtuse

our skull whiplash

their bones awhirl

there bones a world

A face being a shrine is a most Japanese allusion, as Shinto shrines are a fixture in many Japanese homes where food is placed for departed loved ones. Is Joritz-Nakagawa deconstructing the body in a playful Dem Bones manner (as in “the toe bone connected to the foot bone,” etc.)? Also, note the music created with words such as “morsel” and “torso,” “brain” and champagne,” as well as in the final couplet, “awhirl” and “a world.”

There is a heartbeat rhythm built into the meter, as carefree as a nursery rhyme--one of those slightly morbid ones that we love as children and fondly recall as adults.

This is Jane Joritz-Nakagawa’s fourteenth poetic work put out in the span of (take a breath) ten years! Obviously, she is deeply committed to poetry and writing, but not just her own. Joritz-Nakagawa has encouraged other English-language writers in Japan by founding The Japan Writers’ Conference (an annual event now overseen by fellow poets John Gribble and Bern Mulvey). She has also founded listserves to further encourage and connect with the work of English-language writers in Japan, especially ones living in more remote areas such as herself. Not to mention, she is a committed and well-regarded teacher in her field. What this preamble is leading to is an observation of how, over the years, she has found a voice and technique that reflects not only her ethics and commitment, but also her place in two cultures. Her work can be described as abstract and experimental, while also being satisfyingly, deeply somatic. The reader feels his or her way through the poetry more than anything else, and it is a result of the kind of literary alchemy that Joritz-Nakagawa has honed over time.

Originally from Illinois, Jane Joritz-Nakagawa has resided in Japan for some time. Her ninth poetry book, <<terrain grammar>>, will be published in 2017. An anthology of innovative transcultural poetry, with brief accompanying essays, titled women : poetry : migration [an anthology], which Jane is currently editing, is forthcoming from Theenk Books. Her recent work includes Distant Landscapes (Theenk, 2015) and the chapbook, Diurnal (Grey Book Press, 2016). She can be reached via [email protected].