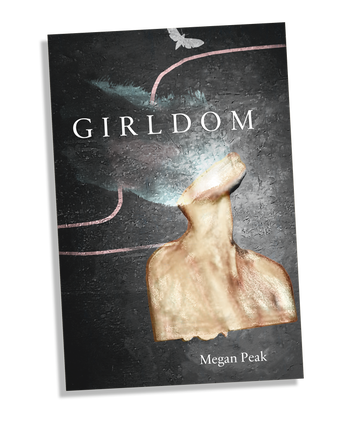

Girldom by Megan Peak

Paperback: 74 pgs

Publisher: Perugia Press (2018)

Purchase @ Perugia Press

Review by Jennifer Martelli.

In her poem, “Sisters of Lake Pontchartrain,” Megan Peak writes

I think of

valleys made full by floods, daughters

born of gulfs. O, how she dove for him

how his name was a knife unto her belly.

The poems in Peak’s collection, Girldom—winner of the Perugia Press Open Reading—lay out the body as the other, as the mother, and as the body violated. This realm of “teendom,” of “girldom”—is one of monstrosities and hybridity. The girl is in a state of morphing, “girl, woman, girl, woman,” into womanhood, into nature; the body is violated and distorted by sexual assault, but pieced back together in a different form. Yet, throughout these metamorphoses, Peak maintains a singular voice:

Behind it I am cloaked,

forever dark in my girl-head, a womb

made of stones. What can I say--

our bodies are tragic houses.

Peak’s descriptions of women—the speaker, the sister, the mother—are formed by their motivations. They become part-human, hybrids. In “Gulf Coast, 6th Grade,”

Older girls drip like amber

bottles of ale, warm in the palms of some

men on a binge.

The speaker’s mother, after slapping her other daughter, hovers “like a busted satellite over the wheel.” The descriptions of the self are often entwined with natural images, small at times and vulnerable: “I can be a twig-woman in the grass. / Small in a man’s yard.” There is a portentous menace to these creatures. In “Girldom As Spinning Bottle,” the young speaker states:

Your world

is one where the rules are cruel, where boys

twirl every empty can, where girls splinter

like oak after oak after oak.

As I read Girldom, I realized the book is a sister/daughter of Elizabeth Bishop’s Geography III. Both collections confront the horror surrounding the body, the sense of “otherness” from the self. Peak’s poem “Stinger in the Wound” illustrates this pushing away from the female-ness of the speaker and the body as a legacy when she writes, “Like any daughter, I am afraid of my body & boys . . . .” as brilliantly as Bishop’s young self, terrified at the aunt’s vulnerability in her poem “In the Waiting Room.” The sexual violence which surrounds the images in Peak’s book is personified in “City with Two Fingers in its Mouth”:

the gutters holler

obscenities as I pass—thin slats looking up my skirt,

whistling garbage, Vivaldi, sex . . . .

I read this as a companion to Bishop’s “Night City,” when she writes, “The city burns tears. . . the city burns guilt.” This city of rape, too, morphs, becomes animalistic in Girldom:

The knuckled city burns

its grimy lights, hissed

like wind coiling through a metal grate.

In “Time Lapse of a Young Woman Giving a Statement,” the speaker observes

Stars the size

of brass badges cock and swivel

above the horn of a city.

The language of sexual assault is a specialized language, spoken in this city of Girldom, the meanings of things slippery, surprising. Peak’s examination of words—naming the violence—is both an accusation and a recrimination. “But/what are you really asking?” the speaker demands in “When Asked If I Said ‘No’.” I’m intrigued by the conversation with the poem on the facing page, “What I Don’t Tell My Mother About Ohio,” which opens with, “Daughters tell lies. We are lovelier/this way.” But, this inability to tell the truth of assault does not preclude the need for love. In “Grief Knot,” Peak describes this muteness:

Like a cat without

its tongue, matted with burrs, tangled

and neurotic, I can’t help but rub

my mangy hair against the pane

of somebody’s window.

Language, or the need for language, is part of the healing and the scarring. In “Violence,” the speaker attempts to describe the “dark zones” in the body. “It’s hard to be cold without/hurting somewhere,” Peak writes, “It’s like a birth at the back of my throat.”

The rape, which occurred outside in the snow (“I felt him slide into me, the hole//our feet made in the snow”) is countered by images of flowing water, a thawing. In "Study of a Flood," Peak begins and ends the poem with water moving: “A river runs through my chest in the shape of a long blue woman . . . . Left open, a small brass clock calling: high tide, high tide, high tide.” The healing is articulated and shaped as a woman, too:

Tell me . . . that word

burden won’t always wear the face

of a woman.

It’s as if the ability to state and limn with word or contour the damage are integral to the healing:

What I need becomes

what I am: a line of women

with raised flags. I think: I’ve room

for love.

Girldom is an accounting of violence, of the burden of shame and guilt, but also of regeneration of language from that violence. In “Wasp & Nettle,” Peak writes, “There’s no other way I’d have her be,/nothing I would tell her if I could.” Just as Elizabeth Bishop presents the moose as female, as “a she,” in her famous poem, Peak allows for the “grand, otherworldly.” We, as witnesses and readers, can feel joy. Peak’s voice is a constant guide. Throughout our visit to Girldom, Megan Peak reminds us of “ . . . heaven: a girl/with a mouth who knows how to use it.”

Megan Peak received her M.F.A. in Poetry from The Ohio State University, where she was former Poetry Editor at The Journal. Her first book of poetry, Girldom, won the 2018 Perugia Press Prize from Perugia Press and 2019 The John A. Robertson Award for Best First Book of Poetry from the Texas Institute of Letters. She lives in Fort Worth, TX with her son, Auden. Her book can be found here.