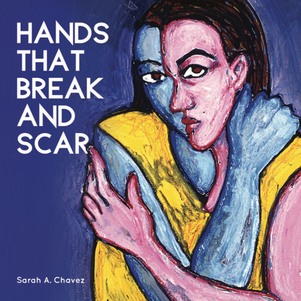

Hands That Break and Scar by Sarah A. Chavez

Paperback

Publisher: Sundress Publications (2017)

Purchase: @ Sundress Publications

Review by Jennifer Martelli.

Our hands have two sides: the soft or callused lighter-shaded palm and the suntanned, veiny back of the hand. They can caress or work, create art or harm, they can draw blood. In Sarah A. Chavez’s poem, “When She Asked Was I Afraid of Needles,” she writes:

I’ll go first, I said, spreading my thumb

and pointer finger to flatten the web

of my hand. Now we will be hermanas, she said

and kissed me on the cheek before dragging

the needle across my outstretched skin.

In her debut collection of poetry, Hands That Break and Scar, Chavez masterfully studies these flip-sides of ethnicity, and of course, of hands. The book creates a friction of contrasts: light and dark skin, nuance and color, the printed word and the white space.

The contrasts within the speaker’s world are ethnic and emotional. Chavez combines language and color to create the experience of integration. In the opening poem, “The Mexican-American Parade, “ the speaker sees and hears the differences: “my dad took me and my light-skinned sister” and “people who looked more like my dad/than me walked around, rolling their Rs . . . .” Chavez claims the symbolism of the Mexican and American flags printed on a white T-shirt, the flag clutched by eagles’ talons:

mirror images of one another,

reflections across water, across a border.

The corners of the flags both dripped red,

bled into a pool beneath their talons, filling

the lower white space of the shirt.

This experience of color against white is embodied in the layout of the book. Hands That Break and Scar is a square, 8” X 8” book. While some of Chavez’s poems use a longer line, which fits nicely in a page this size, most don’t require the extra space and leave almost half the page white. As a reader, I was drawn to the contrast of print and non-print. Chavez brilliantly sculpted her collection; we are actually experiencing the contrast with our eyes, holding it in our hands.

Chavez’s use of the body gives the collection a tension, as if disparate “molecules” were trying to unite into one being. In “On A Summer Afternoon,” the speaker muses:

I think I like the idea of our molecules combining--

first hand to thigh, then hand to face, then chests

and legs. Foreheads and noses, eyes and lips.

I imagine that, like pointillist paintings, from a distance

our fragments together must look plenary, sublime.

The accuracy of a “pointillist painting” is echoed by Chavez’s imagery of the tattoo throughout the book. There are few things more intimate and physical as a tattoo, which demands close detail, skin on skin, color, pain, and blood. As the Turtle, the tattoo artist says in “My First Tattoo,” tattoos “were a sign of courage for the Mayans. Tattoos/were an offering to the Aztec gods and placement was sacred. Our skin/the most divine gift we could give.” Chavez pays homage to skin art, “the tattoo proof that she touched me, that her hands/and my back were courageous works in harmony: she, the tattoo, and I.”

If the hands must “break and scar” the skin to create this art, some hands are broken, scarred. The speaker is in awe of hands: how they convey lifetimes. In “Grandma’s Hands,” Chavez contrasts the grandmother’s hands, missing fingers by physical work, with colors and gems:

As a child I would touch her

gaudy rings—their costume gems

big enough to consume

those half fingers--

just to feel

the soft tops of her hands, so unlike

her palms, calloused

from pruning pomegranate

and orange trees.

Just as the speaker places herself in the care of the tattooist’s hands, so does she with her grandmother, “lay my right hand in her/right hand and my left in her left,/her strength enough for both of us.” The ancient landscape is worked by damaged hands, like Lupe Chavez’s and the speaker’s father’s hands, which can still peel an orange “with one hand a sharp knife.” In the paean, “Praise this Land, The San Joaquin Valley,” Chavez writes

Praise your ancestors who loved the land like their own flesh

and massaged its parched roughness with water and racheras, whose tan

fingers sank deep into the soil to make holes into which they whispered

La tierra, te alabo.

Hands that Break and Scar demands a full reading with the senses. This collection speaks to a vivid, visceral mingling of blood that soaks deeply into the page, always nourishing the reader with is abundance of fruit, color, and its “rainbow of children.” It is a love song to the world, in spite of its dangers. “Praise me,” Chavez writes, “Praise me, you made me.”