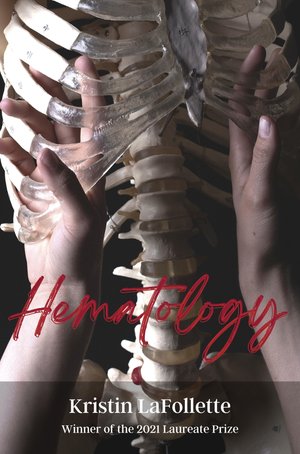

Hematology by Kristin LaFollette

Hematology by Kristin LaFollette

Paperback 107 pages

Publisher: Small Harbor Publishing, 2021

Purchase: HERE

Paperback 107 pages

Publisher: Small Harbor Publishing, 2021

Purchase: HERE

Our Bodies Will Remember : A Review of Hematology

by Rebecca O’Bern

Poet Kristin LaFollette invites us in to the catacombs of self, those deep recesses in our past, present, and future identities and relationships explored through imagery of biology, body, and blood. With a make-up of sixty-percent water, and blood that’s made up of ninety-percent water, at the core of a human being is a substance, a message of sight and breath licked in the fluids of our ancestors. Hematology carefully divides one cross section and then another, displays of our bodies as inheritance. Winner of the 2021 Laureate Prize with Small Harbor Publishing, this collection takes readers on a journey of an identity unfolding, much like DNA strands, with LaFollette expertly training us on how to scan her cells and bones.

This full-length poetry book is divided into three parts, each addressing the speaker’s core relationships in life, including the one with herself. Beginning in Part I, a second-person point of view invites readers from one page to the next, coupled with a deep sense of loss. In “Women,” the first poem in the collection, she writes: “There is a new language, and I know it because of you.” Then, the journey on the footpath continues, as unexpected comparisons quickly emerge with repeated imagery and motifs of bone, marrow, blood, hunters, trees, and roots. Thus, a speaker evolves before our eyes, from hunter to merchant, from child to adult, from the blank canvas of a body to the now.

A body doesn’t come blank, though, of course, and LaFollette reminds us of this fact repeatedly, as we all begin from others. In short, Hematology gets at what it means to be human, then and now—quickly, and then keeps us at this level. “My warm blood is red with / the minerals of people / / with dark skin, / eyes, / hair,” she writes in the poem “Hemoglobin.” Then, suddenly, another aspect of self—daughter, family, and placement in it, such as in the poem “Middle Child.” Loss then mixes with grief and a coming to terms—perhaps, even, a coming-of-age. If not just of the speaker as a separate soul, one of civilization and humanity.

If Part I can be represented with the imagery of blood, then Part II is water, with titles such as “The Sea-Thing Child” and “Movement of Water.” And if Part I explores loss, then Part II investigates longing, with more imagery of the body—skin, scapula, and white blood cells.

Further identity is explored as the collection continues, seen in poems such as “The Introvert.” LaFollette shows us, importantly, that identity goes deep, that there is much more to a person than skin or origin. There’s also the individual, a unique personality who is current and modern, but not necessarily stagnant—the I-alone self of now. This full person is at the center of this work, splayed in all directions in various iterations of reflection and interaction.

In “Adult Teeth,” we’re presented with this: “our bodies will remember, will hold / watermarks of the place in collagen / & roots for years to come as if no time / / has really passed at all—.” The passing of time, then, becomes the stillness of now, within the circle of life. There are many emerging characters who gather with the speaker, too: sister, friend, boy, girl. “The trees begin to absorb him—/ The trees sense the last bit / / of life in his skin,” LaFollette writes in “Symbiosis.” Because, of course, from sky, sea, and ground we come and to which will return, and so in these transitions our connections live on, as in us.

Then, just as readers find themselves contemplating placement in the universe, we are brought back to what’s held together in our familial bodies. “What I know now: My skeleton is burdensome like my mother’s / / quick to take on water and slow to heal.” This collection clearly uncovers and unearths pain and passage with beauty in the form of unexpectedly eerie comparisons with the spinal column.

The body and emotions are related outside of these poems as well, of course, with different parts of the human form historically representing our various intangible aspects of inner worlds, such as with the heart. Not until the sixteenth-century amphitheater at the University of Padua was the functionality of the body even attributed to the brain and nervous system, according to Esther Sternberg, MD, author of The Balance Within: The Science Connecting Health and Emotions. While academic study of anatomy and biology have gone far since then, Hematology shows us that poetry has too, from the tangible to the ineffable quality of being in the operating room, slicing with a scalpel through who we are and from where we originated.

This poetry collection demonstrates not only how people grow apart and together but how the self also changes along with the natural world—as we are, in fact, a part of nature, not separate from this world; we are organic. If Part I is loss, and Part II is longing, then Part III is rejoining. Part III, then, becomes the collective, the hive—with the “we” of seasons changing front and center, of siblinghood, of kin, of other, of sameness.

A coming to terms evolves at this point in the collection, and readers will welcome this reprieve. “Eventually,” LaFollette writes in the final poem, “I realize not all things can be fixed (cured) with water.” Rather, it is this: blood, water, and bone combine for an inspiring tribute to a self, with such conceptualizations and identities as introvert, middle child, person with ancestors with dark skin and eyes, person with relationships with boys and girls. Importantly, personhood unfolds throughout this book, just as DNA unfolds throughout a lifetime, defining who we are based on where we came from and who we are today, a universal searching. Readers will not be disappointed with the unique combinations of medical and anatomical vocabulary that drips, with blood and sweat, from every page.

References

LaFollette, Kristin. Hematology. Small Harbor Publishing, 2021.

Sternberg, Esther. The Balance Within: The Science Connecting Health and Emotions. W.H. Freeman, 2001.

by Rebecca O’Bern

Poet Kristin LaFollette invites us in to the catacombs of self, those deep recesses in our past, present, and future identities and relationships explored through imagery of biology, body, and blood. With a make-up of sixty-percent water, and blood that’s made up of ninety-percent water, at the core of a human being is a substance, a message of sight and breath licked in the fluids of our ancestors. Hematology carefully divides one cross section and then another, displays of our bodies as inheritance. Winner of the 2021 Laureate Prize with Small Harbor Publishing, this collection takes readers on a journey of an identity unfolding, much like DNA strands, with LaFollette expertly training us on how to scan her cells and bones.

This full-length poetry book is divided into three parts, each addressing the speaker’s core relationships in life, including the one with herself. Beginning in Part I, a second-person point of view invites readers from one page to the next, coupled with a deep sense of loss. In “Women,” the first poem in the collection, she writes: “There is a new language, and I know it because of you.” Then, the journey on the footpath continues, as unexpected comparisons quickly emerge with repeated imagery and motifs of bone, marrow, blood, hunters, trees, and roots. Thus, a speaker evolves before our eyes, from hunter to merchant, from child to adult, from the blank canvas of a body to the now.

A body doesn’t come blank, though, of course, and LaFollette reminds us of this fact repeatedly, as we all begin from others. In short, Hematology gets at what it means to be human, then and now—quickly, and then keeps us at this level. “My warm blood is red with / the minerals of people / / with dark skin, / eyes, / hair,” she writes in the poem “Hemoglobin.” Then, suddenly, another aspect of self—daughter, family, and placement in it, such as in the poem “Middle Child.” Loss then mixes with grief and a coming to terms—perhaps, even, a coming-of-age. If not just of the speaker as a separate soul, one of civilization and humanity.

If Part I can be represented with the imagery of blood, then Part II is water, with titles such as “The Sea-Thing Child” and “Movement of Water.” And if Part I explores loss, then Part II investigates longing, with more imagery of the body—skin, scapula, and white blood cells.

Further identity is explored as the collection continues, seen in poems such as “The Introvert.” LaFollette shows us, importantly, that identity goes deep, that there is much more to a person than skin or origin. There’s also the individual, a unique personality who is current and modern, but not necessarily stagnant—the I-alone self of now. This full person is at the center of this work, splayed in all directions in various iterations of reflection and interaction.

In “Adult Teeth,” we’re presented with this: “our bodies will remember, will hold / watermarks of the place in collagen / & roots for years to come as if no time / / has really passed at all—.” The passing of time, then, becomes the stillness of now, within the circle of life. There are many emerging characters who gather with the speaker, too: sister, friend, boy, girl. “The trees begin to absorb him—/ The trees sense the last bit / / of life in his skin,” LaFollette writes in “Symbiosis.” Because, of course, from sky, sea, and ground we come and to which will return, and so in these transitions our connections live on, as in us.

Then, just as readers find themselves contemplating placement in the universe, we are brought back to what’s held together in our familial bodies. “What I know now: My skeleton is burdensome like my mother’s / / quick to take on water and slow to heal.” This collection clearly uncovers and unearths pain and passage with beauty in the form of unexpectedly eerie comparisons with the spinal column.

The body and emotions are related outside of these poems as well, of course, with different parts of the human form historically representing our various intangible aspects of inner worlds, such as with the heart. Not until the sixteenth-century amphitheater at the University of Padua was the functionality of the body even attributed to the brain and nervous system, according to Esther Sternberg, MD, author of The Balance Within: The Science Connecting Health and Emotions. While academic study of anatomy and biology have gone far since then, Hematology shows us that poetry has too, from the tangible to the ineffable quality of being in the operating room, slicing with a scalpel through who we are and from where we originated.

This poetry collection demonstrates not only how people grow apart and together but how the self also changes along with the natural world—as we are, in fact, a part of nature, not separate from this world; we are organic. If Part I is loss, and Part II is longing, then Part III is rejoining. Part III, then, becomes the collective, the hive—with the “we” of seasons changing front and center, of siblinghood, of kin, of other, of sameness.

A coming to terms evolves at this point in the collection, and readers will welcome this reprieve. “Eventually,” LaFollette writes in the final poem, “I realize not all things can be fixed (cured) with water.” Rather, it is this: blood, water, and bone combine for an inspiring tribute to a self, with such conceptualizations and identities as introvert, middle child, person with ancestors with dark skin and eyes, person with relationships with boys and girls. Importantly, personhood unfolds throughout this book, just as DNA unfolds throughout a lifetime, defining who we are based on where we came from and who we are today, a universal searching. Readers will not be disappointed with the unique combinations of medical and anatomical vocabulary that drips, with blood and sweat, from every page.

References

LaFollette, Kristin. Hematology. Small Harbor Publishing, 2021.

Sternberg, Esther. The Balance Within: The Science Connecting Health and Emotions. W.H. Freeman, 2001.

A writer, singer/musician, and photographer, Rebecca O'Bern's work has appeared in Notre Dame Review, Whale Road Review, Barely South Review, Storm Cellar, Hartskill Review, and elsewhere. Recipient of the Leslie Leeds Poetry Prize, she’s also been awarded honors from UCONN, Connecticut Poetry Society, and Arts Café Mystic. She serves as co-editor-in-chief of Mud Season Review and on the board of directors of Burlington Writers Workshop.