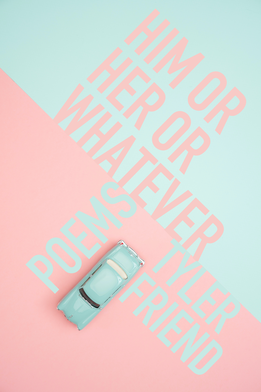

Him or Her or Whatever by Tyler Friend

Him or Her or Whatever by Tyler Friend

Paperback: 102 pgs

Publisher: Alternating Current Press (2022)

Purchase @ Alternating Current Press

Paperback: 102 pgs

Publisher: Alternating Current Press (2022)

Purchase @ Alternating Current Press

Review by Rachel Stempel.

Tyler Friend’s debut full-length collection, Him or Her or Whatever, posits the pronoun as an accusation, illuminating the ways syntax can affirm or challenge what we know, how it can be both weapon and refuge. This is trans poetry—trans from the Latin meaning “across, over, beyond.” Friend’s lyric is unpretentious, which is not to say easy—like a parse tree, it lays bare its components, calling attention to the precariousness of its branches. In “First [comma],” Friend writes: “The first time a girl kissed me—/ I wanted to write, the first time/ I kissed a girl,” then, “The first time I kiss you—I wonder/ if I’ll ever kiss you; I wonder if you’ll ever kiss me”. Hypnotic the repetition may be, what serves more to disorient is the semantic shifts that occur with each remediation of the kiss in question. This is one of many lingual confrontations through which we’re guided.

Prefacing part one of the three-part collection is “They”, a poem opening with an affirmation: “Yes, I contain myself, multitudinous/ & mountainous. I can be hard to navigate.” I am personally sold on any queer poetry that alludes to Walt Whitman not because I am a fan of Whitman but because if Whitman gave us anything, it’s a model for a poet’s god-complex and that nature is, fundamentally, queer. Friend’s repurposing of this sentiment reads as a disclaimer. An admission of difficulty for the other, which is an implicit acknowledgment of the other. Is it us? How, then, do we interpret the poem’s ultimate line, whose imperative demand is softened by an invitation: “Figure out the sentence structure. Diagram me, would you please?” A challenge?

“Radicalism is sexy. We’re not/ mathematicians here.”

In “I, Zeus,” Friend writes: “Men can marry you, but women—/ we can break you.” This presupposes three separations: between “men” and “you,” between “women” and “you,” and between “you” and “we.” Where do “you” stand? Friend’s sonically delicious verse entices us to want to settle on a side, but language is fluid and unsettling. And this is where we uncover possibility. How we interpret the “you” changes, appealing to our most basic needs of communication: locating ourselves. The breadth of allusion spans centuries as these poems’ speakers try to locate themselves as well: poems written after Hilda Doolittle, R.E.M. epigraphs, and an homage to Tinder:

“is the me I’m talking about really just my body?

What if me is not my body? Or, worse, what if it is?”

The momentum propelling the collection is palpable, from the confessional—“I/ am flying back to where lichen// drops, dead:// cinders & ash & you/ & your arrogance”—to the comedic—“Broccoli/ is the least sexy veggie, but/ I would totally fuck a tree.” Friend blends grounding public symbolism—botany, ecology, and pop culture—with an intimate, anecdotal voice, constructing a new mythology of self that we—whoever “we” might encompass—needn’t understand to witness.

“But see, I name me. Me.”

Tyler Friend’s debut full-length collection, Him or Her or Whatever, posits the pronoun as an accusation, illuminating the ways syntax can affirm or challenge what we know, how it can be both weapon and refuge. This is trans poetry—trans from the Latin meaning “across, over, beyond.” Friend’s lyric is unpretentious, which is not to say easy—like a parse tree, it lays bare its components, calling attention to the precariousness of its branches. In “First [comma],” Friend writes: “The first time a girl kissed me—/ I wanted to write, the first time/ I kissed a girl,” then, “The first time I kiss you—I wonder/ if I’ll ever kiss you; I wonder if you’ll ever kiss me”. Hypnotic the repetition may be, what serves more to disorient is the semantic shifts that occur with each remediation of the kiss in question. This is one of many lingual confrontations through which we’re guided.

Prefacing part one of the three-part collection is “They”, a poem opening with an affirmation: “Yes, I contain myself, multitudinous/ & mountainous. I can be hard to navigate.” I am personally sold on any queer poetry that alludes to Walt Whitman not because I am a fan of Whitman but because if Whitman gave us anything, it’s a model for a poet’s god-complex and that nature is, fundamentally, queer. Friend’s repurposing of this sentiment reads as a disclaimer. An admission of difficulty for the other, which is an implicit acknowledgment of the other. Is it us? How, then, do we interpret the poem’s ultimate line, whose imperative demand is softened by an invitation: “Figure out the sentence structure. Diagram me, would you please?” A challenge?

“Radicalism is sexy. We’re not/ mathematicians here.”

In “I, Zeus,” Friend writes: “Men can marry you, but women—/ we can break you.” This presupposes three separations: between “men” and “you,” between “women” and “you,” and between “you” and “we.” Where do “you” stand? Friend’s sonically delicious verse entices us to want to settle on a side, but language is fluid and unsettling. And this is where we uncover possibility. How we interpret the “you” changes, appealing to our most basic needs of communication: locating ourselves. The breadth of allusion spans centuries as these poems’ speakers try to locate themselves as well: poems written after Hilda Doolittle, R.E.M. epigraphs, and an homage to Tinder:

“is the me I’m talking about really just my body?

What if me is not my body? Or, worse, what if it is?”

The momentum propelling the collection is palpable, from the confessional—“I/ am flying back to where lichen// drops, dead:// cinders & ash & you/ & your arrogance”—to the comedic—“Broccoli/ is the least sexy veggie, but/ I would totally fuck a tree.” Friend blends grounding public symbolism—botany, ecology, and pop culture—with an intimate, anecdotal voice, constructing a new mythology of self that we—whoever “we” might encompass—needn’t understand to witness.

“But see, I name me. Me.”

Tyler Friend was grown—and is still growing—in Tennessee, and they received their MFA from Vermont College of Fine Arts. Tyler is the author of Him or Her or Whatever (Alternating Current Press, 2022) and the chapbook BUNKER, which is available in Third Man's "Literarium" book vending machine. Their poems have also shown up in Tin House, Hobart, and Hunger Mountain. They edit Francis House, design for Eulalia Books, teach high school and undergrad, work at a library, and befriend all the cats.