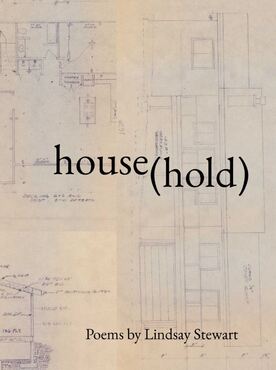

House(hold) by Lindsay Stewart

Ordinary Distance: A Review of House(hold) by Lindsay Stewart

Review by Grace Li.

House(hold), Lindsay Stewart’s debut chapbook, is a quiet, intimate world populated chiefly by four family members, but also monsters, mythology, and enumerated mouths, arms, and hearts. As befitting the chapbook form, the book stays house-sized while offering windows into other places and worlds, ultimately keeping pace with the quiet wonders of ordinary life.

The book opens in “Blueprint from below,” with the four principal players in the book and the imagined room in which we’re introduced to each of them. An introduction to this “house(hold)”, the writer holds them all in this room and offers this to the reader: “someone is standing in the mirror / holding their pulsing heart not / like a shock but like some bright question.” This image captures the tone of Stewart’s project, in which many of the poetic payoffs don’t so much arrest the reader as quietly occur to them mid-conversation.

The book’s concept of distance is particularly compelling and unusual. Distance is not laden with estrangement or emptiness, but as ordinary as any other unit measurable by scale or verse. And the dichotomy between distance and closeness collapses in all the spaces that form a “house(hold).”

A recurring theme I was taken by is the idea of not quite knowing these most beloved people, the other members of the household- the lack of knowing not in spite of closeness, but perhaps because of it. She notices of her father the observant details that slowly accumulate over a life- “He sits next to me, his weight in the chair / and he, too, borrows spare seconds to inhale”. Yet these often quiet observations are also aware of the gaps between what one knows.

“I recognize how far apart we / are—she finds my part easily, with her fingers-- / even at the kitchen table, as she braids my hair,” she writes of her twin sister. It’s a strange feeling that we are all somewhat familiar with, that Stewart articulates beautifully. This is no cause for sadness, but of accepting the wonder of unknowing.

This is a book that ventures into the otherworldly even as it keeps returning to the well-worn landscapes of home. We’re first introduced to the mother figure, a recurring, morphing figure of power and gentleness, as an octopus in the aptly titled “The mother”: “Imagine her, perched, / pale and love-long, / in some dark shelf, / knowing she will / never meet what / she has made, and / making, making anyway.” Soon we’re introduced to another many-shadowed figure: Medusa, a character reimagined in several poems, a feminist reclaiming of monster. Monsterhood is protection, she considers in “Aegis”: “And like the long-locked / of us delicately do, she shed her hair; a snake / here, a snake there.”

Stewart’s affinity for remaking myth is mirrored in her interest in contemporary approaches to structured form, such as the sestina and duplex. Stewart’s strengths play to these deliberately measured but conversational forms of lineation, constructing a sort of scaffolding in which these spaces can become inhabited rooms. Over the course of the chapbook, one grows more familiar with the writer’s particular music: “To know you now, a man of action and easy silence / I have to understand the things you won’t do,” she writes in “I know you, mostly.” These often unassuming aphorisms materialize quietly within these formal spaces.

The penultimate poem “An encyclopedia of my mother and other immovable objects” converges the scales of grandness and intimacy that Stewart holds within the book. The Northern Californian setting which is suffused throughout the poems materializes as an icon in the Golden Gate Bridge, overlapping with the vision of her mother. She imagines the bridge deciding to move: “braids of steel wire with / frayed ends left flying: / suspensions snapped. / I’m sorry, she said. / The moon got in my eyes.”

These poems are inhabited by monsters and snakes, bridges and oceans, but they, like all things, go towards home and the people who make it. Not gods in their mystery, but people in their greater mystery. It's fitting that the same poem ends on this note, “As far as I’m concerned / my mother is quietly making and / unmaking the world in the next room.” As the book looks to the gods and myth- and the bridge is one such myth- it brings the idea of gods down to the human level; the idea of worlds down to eye level. Praise is what we offer for the gods, but poetry is what we offer for the people around us. “Wait, I take it back,” Stewart writes in “Behind the bar”- “You’re nothing like a god, because you’re / here.”

Review by Grace Li.

House(hold), Lindsay Stewart’s debut chapbook, is a quiet, intimate world populated chiefly by four family members, but also monsters, mythology, and enumerated mouths, arms, and hearts. As befitting the chapbook form, the book stays house-sized while offering windows into other places and worlds, ultimately keeping pace with the quiet wonders of ordinary life.

The book opens in “Blueprint from below,” with the four principal players in the book and the imagined room in which we’re introduced to each of them. An introduction to this “house(hold)”, the writer holds them all in this room and offers this to the reader: “someone is standing in the mirror / holding their pulsing heart not / like a shock but like some bright question.” This image captures the tone of Stewart’s project, in which many of the poetic payoffs don’t so much arrest the reader as quietly occur to them mid-conversation.

The book’s concept of distance is particularly compelling and unusual. Distance is not laden with estrangement or emptiness, but as ordinary as any other unit measurable by scale or verse. And the dichotomy between distance and closeness collapses in all the spaces that form a “house(hold).”

A recurring theme I was taken by is the idea of not quite knowing these most beloved people, the other members of the household- the lack of knowing not in spite of closeness, but perhaps because of it. She notices of her father the observant details that slowly accumulate over a life- “He sits next to me, his weight in the chair / and he, too, borrows spare seconds to inhale”. Yet these often quiet observations are also aware of the gaps between what one knows.

“I recognize how far apart we / are—she finds my part easily, with her fingers-- / even at the kitchen table, as she braids my hair,” she writes of her twin sister. It’s a strange feeling that we are all somewhat familiar with, that Stewart articulates beautifully. This is no cause for sadness, but of accepting the wonder of unknowing.

This is a book that ventures into the otherworldly even as it keeps returning to the well-worn landscapes of home. We’re first introduced to the mother figure, a recurring, morphing figure of power and gentleness, as an octopus in the aptly titled “The mother”: “Imagine her, perched, / pale and love-long, / in some dark shelf, / knowing she will / never meet what / she has made, and / making, making anyway.” Soon we’re introduced to another many-shadowed figure: Medusa, a character reimagined in several poems, a feminist reclaiming of monster. Monsterhood is protection, she considers in “Aegis”: “And like the long-locked / of us delicately do, she shed her hair; a snake / here, a snake there.”

Stewart’s affinity for remaking myth is mirrored in her interest in contemporary approaches to structured form, such as the sestina and duplex. Stewart’s strengths play to these deliberately measured but conversational forms of lineation, constructing a sort of scaffolding in which these spaces can become inhabited rooms. Over the course of the chapbook, one grows more familiar with the writer’s particular music: “To know you now, a man of action and easy silence / I have to understand the things you won’t do,” she writes in “I know you, mostly.” These often unassuming aphorisms materialize quietly within these formal spaces.

The penultimate poem “An encyclopedia of my mother and other immovable objects” converges the scales of grandness and intimacy that Stewart holds within the book. The Northern Californian setting which is suffused throughout the poems materializes as an icon in the Golden Gate Bridge, overlapping with the vision of her mother. She imagines the bridge deciding to move: “braids of steel wire with / frayed ends left flying: / suspensions snapped. / I’m sorry, she said. / The moon got in my eyes.”

These poems are inhabited by monsters and snakes, bridges and oceans, but they, like all things, go towards home and the people who make it. Not gods in their mystery, but people in their greater mystery. It's fitting that the same poem ends on this note, “As far as I’m concerned / my mother is quietly making and / unmaking the world in the next room.” As the book looks to the gods and myth- and the bridge is one such myth- it brings the idea of gods down to the human level; the idea of worlds down to eye level. Praise is what we offer for the gods, but poetry is what we offer for the people around us. “Wait, I take it back,” Stewart writes in “Behind the bar”- “You’re nothing like a god, because you’re / here.”

Grace Li is a poet and educator based in California. Her work has been published in Crazyhorse, Tupelo Quarterly, North American Review, and other publications. She holds a BA from UCLA and an MFA from San Diego State University.