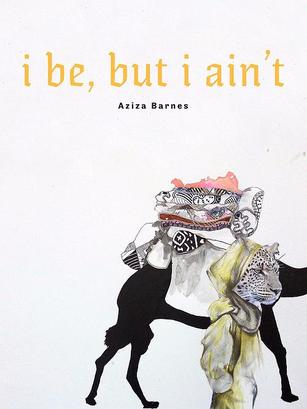

Paperback: 88 pgs

Publisher: Yes Yes Books (2016)

Purchase @ YesYes Books

Review by Len Lawson

Aziza Barnes’ first full-length poetry collection i be, but i ain’t is a funhouse marathon through the quest for identity. The poetry takes readers on an excursion into identity where translucent boundaries bend but don’t break. However, the path is subtly transformative.

We think we are cringing from a bug on the wall in the first poem “how to kill a house centipede…” until Barnes interrogates everything we think we know about spirituality in search of self:

I suppose I am that interested in the body/defeated or the body striving to say

something new about itself like/the position saints die in neck craned arms

crossed legs crossed how they don’t/decompose…to be a saint which means I will

never be a saint never die

Through the death of the centipede, Barnes continues to crawl through the wormhole of contemplating her own death without spiritual overtones. “I hope to be burnt &/thrown not for any spiritual reason unless claustrophobia is a spiritual/reason”. A portrait of Miriam Makeba, a catalyst for the kill, continues the march to anti-salvation:

…her eyes closed & sometimes not/& yes, it is this that I find least human to

sing without your eyes/open like sleeping next to someone you love it is a

symmetry a faith…an amorphous congregation of this

A death in nature brings Barnes closer to an altar of mortality and a reluctance to acquiesce to death’s religious rites. The conflict of this first poem sets the table for the continual dichotomy of self.

The title of the book itself initiates the complexity in identity. In the poem “we have no conception of bastard”, the subtle arrival of the conflict emerges once again. We think we are dancing to Michael Jackson in Elmina with Ghanaians until Barnes makes a black declaration of independence for the ages when asked “what is ‘black?’” She assumes the figurative platform of Martin Luther King’s Lincoln Memorial speech and creates her own “I Have a Dream” moment:

black is i gonna go. i finna go. i go./i be but i ain’t. i bastard./i done walked with

a name i couldn’t shake & now i gone.

The essence of the collection is encapsulated in these thirty words. The conflict morphs from spiritual to racial identity. Blackness is dancing in Ghana and still not being certain of who you are. Blackness is being free on a dance floor and still conflicted about your own name. Blackness is a holy dance to music by Michael Jackson, who is the epitome of the struggle with one’s race, and still being unsure of why the blood is beating violently in your veins. However, Barnes knows she has mastered the art and ironic liberation of exploring the conflict on all sides before issuing the declaration: “I regurgitated the sure-fire cure to any slavery”.

Several poems feature “the mutt” as a symbol and center of all conflicts: spiritual, racial, and generational. By definition in the piece entitled “mutt”, the character is “a mongrel…half & half”, a mixed breed already in conflict by birth. In the poem “the mutt looks at her polycystic ovaries on a sonogram”. Barnes first identifies the mutt by body image: “Hair on my chin/they give me. I comb up my some sunlight to touch what I don’t want of my face.” She then launches an investigation into the bloodline that has created the mutt. “The women/in my family grow tumors before/children. They miscarry./They piss on what they want/to keep safe.” In an effort to break this curse, the mutt promises hope for the next generation:

If I die anyway in the street I want/my children to find the names/for my

children./I write them in the backs of books. ElBird & Octavia & Calvin

Cornelius IV…I won’t yield/& I won’t yield.

The promise ensures that the next generation will not live in doubt and internal conflict as the mutt has. Finding their names written ensures a purpose for the children beyond conception and beyond just their physical features the mutt has analyzed in herself. Their future will not “show up black” like the ovaries on the screen. They have been given the birthright of light.

The identity conflict can also be seen in Barnes’ award-winning poem “my dad asks, ‘how come black folk can’t just write about flowers?’” The father’s question invokes the i be, but i ain’t mantra of race. The question is really, “Why can’t blacks just be happy (with themselves)?” The question denies black people the very liberation of identity Barnes seeks through the poetry in this book. The poem describes how neighbors call police to the speaker’s home apparently for her and her friends creating a disturbance at their house party. She establishes identity early in the poem letting readers know right away, “there’s a party at my house, a house held by legislation vocabulary & trill, but hell, it’s ours” and later “it be our road. we own it.” The speaker’s ownership and presence in the neighborhood indicates the i be clause of her identity. Notwithstanding, when the police interrogate her and her friends the foil clause i ain’t is not far behind.

this your house?

I say yeah. she go

can you prove it?

I say it mine.

The fact that the officer is “blk & short & a woman, too” presents the astounding internal conflict of the speaker role played between her and the officer. This dialogue can be seen as the i be, but i ain’t conflict played out externally. Although the speaker establishes her identity to the officer, the officer still needs proof of the speaker’s ownership (ID) thus proof of her existence. Therefore, the father’s question in the title smacks of a misdiagnosis of the black experience. Barnes shows that black identity is continually interrogated even on one’s own street at one’s own home and even by another person of color! In fact, the interrogation is by an almost mirror image of the speaker in the form of a black woman. How can black people write about flowers when their identity is constantly questioning them right in front of their faces? Furthermore, throughout the book, although the imagery changes, the dichotomy in this kaleidoscope of conflict is always present.

Barnes does prove her ownership of the text without the need for ID. She owns it with her language and blatantly incorrect grammar. Of course, this is evident in the title. Barnes also summarizes this in the opening lines to the poem “you are here”: “Life be an inarticulate beast.” If this metaphor is true, then there is no need to strive for articulation and Standard American English. Barnes also owns the text with a relentless grip on life experiences. She is able to transcend the present timeline and dance back and forth to and from both sides of the overall conflict with the style of Sugar Ray Leonard or Walter Payton—with sweetness—in their rugged, gritty, respective sports. The grace at which she claims victory on her battlefield of conflict makes Aziza Barnes a worthy voice on the cutting edge of contemporary poetry.

Publisher: Yes Yes Books (2016)

Purchase @ YesYes Books

Review by Len Lawson

Aziza Barnes’ first full-length poetry collection i be, but i ain’t is a funhouse marathon through the quest for identity. The poetry takes readers on an excursion into identity where translucent boundaries bend but don’t break. However, the path is subtly transformative.

We think we are cringing from a bug on the wall in the first poem “how to kill a house centipede…” until Barnes interrogates everything we think we know about spirituality in search of self:

I suppose I am that interested in the body/defeated or the body striving to say

something new about itself like/the position saints die in neck craned arms

crossed legs crossed how they don’t/decompose…to be a saint which means I will

never be a saint never die

Through the death of the centipede, Barnes continues to crawl through the wormhole of contemplating her own death without spiritual overtones. “I hope to be burnt &/thrown not for any spiritual reason unless claustrophobia is a spiritual/reason”. A portrait of Miriam Makeba, a catalyst for the kill, continues the march to anti-salvation:

…her eyes closed & sometimes not/& yes, it is this that I find least human to

sing without your eyes/open like sleeping next to someone you love it is a

symmetry a faith…an amorphous congregation of this

A death in nature brings Barnes closer to an altar of mortality and a reluctance to acquiesce to death’s religious rites. The conflict of this first poem sets the table for the continual dichotomy of self.

The title of the book itself initiates the complexity in identity. In the poem “we have no conception of bastard”, the subtle arrival of the conflict emerges once again. We think we are dancing to Michael Jackson in Elmina with Ghanaians until Barnes makes a black declaration of independence for the ages when asked “what is ‘black?’” She assumes the figurative platform of Martin Luther King’s Lincoln Memorial speech and creates her own “I Have a Dream” moment:

black is i gonna go. i finna go. i go./i be but i ain’t. i bastard./i done walked with

a name i couldn’t shake & now i gone.

The essence of the collection is encapsulated in these thirty words. The conflict morphs from spiritual to racial identity. Blackness is dancing in Ghana and still not being certain of who you are. Blackness is being free on a dance floor and still conflicted about your own name. Blackness is a holy dance to music by Michael Jackson, who is the epitome of the struggle with one’s race, and still being unsure of why the blood is beating violently in your veins. However, Barnes knows she has mastered the art and ironic liberation of exploring the conflict on all sides before issuing the declaration: “I regurgitated the sure-fire cure to any slavery”.

Several poems feature “the mutt” as a symbol and center of all conflicts: spiritual, racial, and generational. By definition in the piece entitled “mutt”, the character is “a mongrel…half & half”, a mixed breed already in conflict by birth. In the poem “the mutt looks at her polycystic ovaries on a sonogram”. Barnes first identifies the mutt by body image: “Hair on my chin/they give me. I comb up my some sunlight to touch what I don’t want of my face.” She then launches an investigation into the bloodline that has created the mutt. “The women/in my family grow tumors before/children. They miscarry./They piss on what they want/to keep safe.” In an effort to break this curse, the mutt promises hope for the next generation:

If I die anyway in the street I want/my children to find the names/for my

children./I write them in the backs of books. ElBird & Octavia & Calvin

Cornelius IV…I won’t yield/& I won’t yield.

The promise ensures that the next generation will not live in doubt and internal conflict as the mutt has. Finding their names written ensures a purpose for the children beyond conception and beyond just their physical features the mutt has analyzed in herself. Their future will not “show up black” like the ovaries on the screen. They have been given the birthright of light.

The identity conflict can also be seen in Barnes’ award-winning poem “my dad asks, ‘how come black folk can’t just write about flowers?’” The father’s question invokes the i be, but i ain’t mantra of race. The question is really, “Why can’t blacks just be happy (with themselves)?” The question denies black people the very liberation of identity Barnes seeks through the poetry in this book. The poem describes how neighbors call police to the speaker’s home apparently for her and her friends creating a disturbance at their house party. She establishes identity early in the poem letting readers know right away, “there’s a party at my house, a house held by legislation vocabulary & trill, but hell, it’s ours” and later “it be our road. we own it.” The speaker’s ownership and presence in the neighborhood indicates the i be clause of her identity. Notwithstanding, when the police interrogate her and her friends the foil clause i ain’t is not far behind.

this your house?

I say yeah. she go

can you prove it?

I say it mine.

The fact that the officer is “blk & short & a woman, too” presents the astounding internal conflict of the speaker role played between her and the officer. This dialogue can be seen as the i be, but i ain’t conflict played out externally. Although the speaker establishes her identity to the officer, the officer still needs proof of the speaker’s ownership (ID) thus proof of her existence. Therefore, the father’s question in the title smacks of a misdiagnosis of the black experience. Barnes shows that black identity is continually interrogated even on one’s own street at one’s own home and even by another person of color! In fact, the interrogation is by an almost mirror image of the speaker in the form of a black woman. How can black people write about flowers when their identity is constantly questioning them right in front of their faces? Furthermore, throughout the book, although the imagery changes, the dichotomy in this kaleidoscope of conflict is always present.

Barnes does prove her ownership of the text without the need for ID. She owns it with her language and blatantly incorrect grammar. Of course, this is evident in the title. Barnes also summarizes this in the opening lines to the poem “you are here”: “Life be an inarticulate beast.” If this metaphor is true, then there is no need to strive for articulation and Standard American English. Barnes also owns the text with a relentless grip on life experiences. She is able to transcend the present timeline and dance back and forth to and from both sides of the overall conflict with the style of Sugar Ray Leonard or Walter Payton—with sweetness—in their rugged, gritty, respective sports. The grace at which she claims victory on her battlefield of conflict makes Aziza Barnes a worthy voice on the cutting edge of contemporary poetry.

AZIZA BARNES is blk & alive. Born in Los Angeles, Aziza currently lives in Oxford, Mississippi. Aziza's first chapbook, me Aunt Jemima and the nailgun, was the first winner of the Exploding Pinecone Prize from Button Poetry, and Barnes' first full length collection of poems, i be but i ain’t, is the winner of the 2015 Pamet River Prize with YesYes Books.