Interview with Amorak Huey

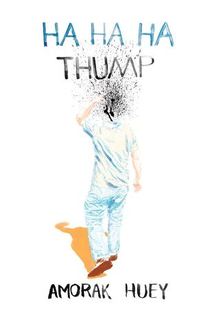

Up the Staircase Quarterly: Amorak, thanks so much for joining us for this interview to discuss your new book of poetry, Ha Ha Ha Thump (Sundress Publications, 2015).

As I was reading, I grew curious about your writing process for Ha Ha Ha Thump. Was this a long term project that spanned several years, or did it come together more quickly? Which parts of yourself did you pull from during the writing of this book?

Amorak Huey: Hi, and thanks so much for the chance to talk about the book. So, yeah, this was a long-term project. I first began sending out the original version of the manuscript in summer of 2011, and as it kept getting rejected, I kept writing more poems. The project morphed and grew and evolved, and eventually I ended up splitting it into two different collections, one of which Sundress eventually took. Even then, it wasn’t done; I worked with Erin Elizabeth Smith (who’s a truly amazing editor) to order and shape the poems into the final form it took. Erin was so helpful. She was like, “This narrative makes no sense, Amorak,” and I was like, “What do you mean, narrative? This is not a narrative,” and she was like, “Well, then quit making it look like a narrative.” Which led me to an entire reordering, a search for more intuitive connections between poems and less of this half-assed, quasi-narrative chronology, which for some reason I’d started with.

As for which parts of myself I pulled from, that’s a really interesting question, and I don’t think it has a simple answer. It’s all me, and at the same time it’s all made up. Every speaker is a persona, right? Which is to say, it’s impossible for a single poem to capture the entirety of a human being, so when we write we’re always picking and choosing parts of ourselves to include in a given poem, which parts to emphasize, which parts to minimize—and also inventing things from whole cloth. I exist in each of these poems, but in varying degrees of truth and imagination. I hope what unites them is my voice, but that’s hard for me to say, the kind of judgment better left for readers.

UtSQ: Ha Ha Ha Thump is divided into five sections. Each section begins with a poem titled “Ha Ha Ha Thump.” I felt that these poems were all quite different in tone, and the phrase “Ha Ha Ha Thump” seems to evolve and change over the course of the five poems. What can you tell us about this title? How did it come to you?

AH: The title comes from a children’s joke: “What goes ha ha ha thump? Someone laughing his head off.” I think maybe poetry can go this way, too, sometimes. I wrote a poem with that title and “someone laughing his head off” as the last line, and eventually, at some point in the collection’s evolution, that became the title of the whole thing. I was thinking about humor as a guiding principle for poetry, the structure of a joke compared with the structure of a poem. Life is like that, I think: everything going along fine until suddenly, thump, your head falls off. Which can be good or bad. Like the top of Emily Dickinson’s head being blown off in her famous definition of poetry. For a long time, the book had just that one “Ha Ha Ha Thump” poem, but very late in the process, when I was working with Erin on the final structure, when I finally realized I needed to obscure any implication that this was a linear narrative collection and find another way to organize the book, I realized it might serve me well to try to come up with other answers to the question. So, what else goes ha ha ha thump? A hyena falling out of a tree. A clown with a heart condition. A Hollywood marriage. And laughter to measure the moment between lightning and thunder. Writing those new poems helped me organize the book.

UtSQ: There are a large number of pop culture-centered poems and pop culture references in Ha Ha Ha Thump. This is a genre of poetry that I am fond of, so I was thrilled to see Star Wars, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, and even Mick Jagger make appearances in your collection. What drew you toward the genre of pop culture poetry? On a larger scale, what significance does pop culture bring to the poetry world as a writing tool?

AH: Pop culture is just part of the air we breathe, I think. Poetry is about language, and pop culture has such an influence on our language. It seems to me that it would be disingenuous for poetry not to engage with pop culture at some point. Not that every poem has to do this, but surely some poems must. We can no longer read, say, Alexander Pope without footnotes explaining his references and diction—that’s because when he wrote “The Rape of the Lock” or whatever, he was writing in the idiom of the time, referring to the culture around him, using the language of the world he inhabited. So writing about “Project Runway” or Han Solo or Tiger Woods, that’s just writing about the world I live in, the world I’m trying to understand, using the language of this time and place.

As I was reading, I grew curious about your writing process for Ha Ha Ha Thump. Was this a long term project that spanned several years, or did it come together more quickly? Which parts of yourself did you pull from during the writing of this book?

Amorak Huey: Hi, and thanks so much for the chance to talk about the book. So, yeah, this was a long-term project. I first began sending out the original version of the manuscript in summer of 2011, and as it kept getting rejected, I kept writing more poems. The project morphed and grew and evolved, and eventually I ended up splitting it into two different collections, one of which Sundress eventually took. Even then, it wasn’t done; I worked with Erin Elizabeth Smith (who’s a truly amazing editor) to order and shape the poems into the final form it took. Erin was so helpful. She was like, “This narrative makes no sense, Amorak,” and I was like, “What do you mean, narrative? This is not a narrative,” and she was like, “Well, then quit making it look like a narrative.” Which led me to an entire reordering, a search for more intuitive connections between poems and less of this half-assed, quasi-narrative chronology, which for some reason I’d started with.

As for which parts of myself I pulled from, that’s a really interesting question, and I don’t think it has a simple answer. It’s all me, and at the same time it’s all made up. Every speaker is a persona, right? Which is to say, it’s impossible for a single poem to capture the entirety of a human being, so when we write we’re always picking and choosing parts of ourselves to include in a given poem, which parts to emphasize, which parts to minimize—and also inventing things from whole cloth. I exist in each of these poems, but in varying degrees of truth and imagination. I hope what unites them is my voice, but that’s hard for me to say, the kind of judgment better left for readers.

UtSQ: Ha Ha Ha Thump is divided into five sections. Each section begins with a poem titled “Ha Ha Ha Thump.” I felt that these poems were all quite different in tone, and the phrase “Ha Ha Ha Thump” seems to evolve and change over the course of the five poems. What can you tell us about this title? How did it come to you?

AH: The title comes from a children’s joke: “What goes ha ha ha thump? Someone laughing his head off.” I think maybe poetry can go this way, too, sometimes. I wrote a poem with that title and “someone laughing his head off” as the last line, and eventually, at some point in the collection’s evolution, that became the title of the whole thing. I was thinking about humor as a guiding principle for poetry, the structure of a joke compared with the structure of a poem. Life is like that, I think: everything going along fine until suddenly, thump, your head falls off. Which can be good or bad. Like the top of Emily Dickinson’s head being blown off in her famous definition of poetry. For a long time, the book had just that one “Ha Ha Ha Thump” poem, but very late in the process, when I was working with Erin on the final structure, when I finally realized I needed to obscure any implication that this was a linear narrative collection and find another way to organize the book, I realized it might serve me well to try to come up with other answers to the question. So, what else goes ha ha ha thump? A hyena falling out of a tree. A clown with a heart condition. A Hollywood marriage. And laughter to measure the moment between lightning and thunder. Writing those new poems helped me organize the book.

UtSQ: There are a large number of pop culture-centered poems and pop culture references in Ha Ha Ha Thump. This is a genre of poetry that I am fond of, so I was thrilled to see Star Wars, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, and even Mick Jagger make appearances in your collection. What drew you toward the genre of pop culture poetry? On a larger scale, what significance does pop culture bring to the poetry world as a writing tool?

AH: Pop culture is just part of the air we breathe, I think. Poetry is about language, and pop culture has such an influence on our language. It seems to me that it would be disingenuous for poetry not to engage with pop culture at some point. Not that every poem has to do this, but surely some poems must. We can no longer read, say, Alexander Pope without footnotes explaining his references and diction—that’s because when he wrote “The Rape of the Lock” or whatever, he was writing in the idiom of the time, referring to the culture around him, using the language of the world he inhabited. So writing about “Project Runway” or Han Solo or Tiger Woods, that’s just writing about the world I live in, the world I’m trying to understand, using the language of this time and place.

UtSQ: What resources did you turn to during your writing of Ha Ha Ha Thump? Were there specific books, songs, movies, articles, or TV shows that inspired you? Were there any personal experiences that directly led you to write these poems?

AH: My inspirations are so varied, it’s hard to pin down anything in particular. I mean, obviously, I was drawing from the specific people and shows and characters explicitly mentioned in the poems: Heidi Klum, Mick Jagger, the Ninja Turtles, etc. One thing about me and pop culture is that I’m more of a dabbler than some poets I know. Other people have obsessions, these areas of culture that they know deeply and intimately; I feel like that level of, I don’t know, is it passion? Expertise? — whatever it is, I feel like it’s missing for me. I tend to be interested in many things on a more shallow level. Like, my friend W. Todd Kaneko has his book, The Dead Wrestler Elegies, which is all intensely focused on pro wrestling. Kiki Petrosino has a huge section in Fort Red Border that’s about an imagined (I assume) affair with Robert Redford; I was inspired by this for my poem in the book “The Poet and the Supermodel (A Rearranged Marriage),” but I was done with the subject in four sections. I tend to be more like that: quickly into and out of a topic. I don’t know, it sort of feels like a failing on my part, some kind of attention deficit or some such. I envy other writers their obsessions. One of my dirty secrets is that I sometimes write in front the television, and the poem I’m working on will come from whatever trashy show is on at the moment I’m writing. I also have a tendency to revisit the pop culture interests of my high school days. Hair band music comes up a lot, for instance, though I’ve put most of those poems in a different manuscript.

UtSQ: If you had to choose, which couple of poems from Ha Ha Ha Thump would you consider your personal favorites? Which characteristics of these poems make them stand (even if only slightly) above the rest for you?

AH: The first one that comes to mind is the last poem in the book, with its way long title: “Ars Poetica Disguised as a Love Poem Disguised as a Commemoration of the 166th Anniversary of the Rescue of the Donner Party.” This poem was partly inspired by Matthew Olzmann’s “Mountain Dew Commercial Disguised as a Love Poem,” and I like to think it achieves what I promise in the title. I might be fooling myself there. I also like the Mick Jagger poem, because it makes me laugh, and because I think it’s out of character for me. (Again, maybe I’m fooling myself.) I read this poem at an AWP offsite event a few years ago, and later in the conference someone said, “Hey, you’re the penis poem guy.” Which is not really how I want to be known, but I’m repeating it here, so maybe part of me does want to be known that way. Was I supposed to answer this question so directly? Or was I supposed to say something about how it would be like choosing a favorite of my children? Because it’s not, really. Oh, and I also have a particular fondness for the Heidi Klum poem and for “She Blinded Me With Molecular Nanotechnology.” These are poems where I think I achieved what I set out to do.

UtSQ: In "Nocturne: Interrogation" you write, "Language is a kind of hunger." Tell us about your first significant literary “hunger.” How did this encounter inspire you, or shape you, into the writer you have become?

AH: One of the things I remember most viscerally about reading as a child — and oh, how I read — was this ache in the back of the throat I would get when I read something that overwhelmed me, this sudden, tangible, physical manifestation of my attachment to the words on the page, the events and characters I was reading about. I remember it most distinctly from books with sad or traumatic endings: Harriet Arnow’s The Dollmaker, Where the Red Fern Grows, The Yearling, Old Yeller, To Kill A Mockingbird — but I also remember it from books in which the character achieves some kind of freedom, or has some great adventure: Treasure Island, Susan Cooper’s The Dark Is Rising series, the Narnia books. I was just in awe of the power of words to get inside me that way, and at some point I became fixated on the idea that I could maybe someday write words that would do that to someone else. I’m still trying.

UtSQ: What was the worst editing or writing advice you have received over the years? What was the best advice you received? Did you follow this advice? Why or why not?

AH: I worked in newspapers for more than a decade, some as a reporter and mostly as an editor, and I worked with a lot of great editors, and a few not-so-great ones. What made the bad ones bad was their desire to impose their own idiosyncrasies onto the text, their unwillingness to listen to the sentence or story in front of them and follow where the language was leading them. This often resulted in silly errors or weirdly awkward sentences in the name of “correctness.” An example: one editor had it in his head that no dialogue tag should ever be “said Jane”; rather it should always be “Jane said.” Now as a rule of thumb, this is fine, but as an absolute? Sometimes the sentence needed to be the other way for reasons of sense or sound or clarity, but this editor would reflexively change it, every time, sometimes ruining a perfectly good sentence in the process. As for how this applies to poetry, I think the same idea is relevant: listen to the sentence; listen to the words; be flexible; don’t force your preconceptions onto a poem. It’s along the lines of what Richard Hugo says in Triggering Town about being willing to let go of the initiating idea of a poem and go where the language takes you. As for the best advice, William Olsen, with whom I worked in grad school at Western Michigan, told me this: “Nothing matters so much to a poem as the state of mind of the poet at the moment of writing.” To me, this means you have to be honest with your readers about why you’re writing something, about what’s at stake for you in the act of creating a poem. Don’t be coy. Don’t hide behind memory, or the alleged factual truth of an experience; instead, be true to the emotional core of the poem. Be willing to be vulnerable on the page. Don’t write to make yourself look smart or moral or emotionally mature. Go for bone. Write the hard stuff, and be honest about why it’s hard.

UtSQ: Finally, Amorak, if you could have a meal with anyone, dead or alive, real or imaginary, whom would it be, and what on earth would the two of you eat?

AH: Jackie Robinson. I read so much about him when I was a kid, and I admire so much what he did for baseball and for American society in general, and I love his spirit, the way he played the game, all fearless and hard-working against unimaginably difficult circumstances. Of course, he was also a world-class athlete, so it’s not like he was getting by simply on guts and hustle. One of my real heroes, and one of the reasons I’m a Dodgers fan. As for what we’d eat, I’ll go with a big greasy pepperoni pizza and Cokes because I’m hungry right now and that sounds delicious.

Amorak Huey is author of the poetry collection Ha Ha Ha Thump (Sundress, 2015) and the chapbook The Insomniac Circus (Hyacinth Girl, 2014). A longtime newspaper editor and reporter, he now teaches writing at Grand Valley State University in Michigan. His poems appear in The Best American Poetry 2012, The Southern Review, The Collagist, Poet Lore, Carolina Quarterly, Quarterly West, and many other journals. Follow him on Twitter: @amorak.

AH: My inspirations are so varied, it’s hard to pin down anything in particular. I mean, obviously, I was drawing from the specific people and shows and characters explicitly mentioned in the poems: Heidi Klum, Mick Jagger, the Ninja Turtles, etc. One thing about me and pop culture is that I’m more of a dabbler than some poets I know. Other people have obsessions, these areas of culture that they know deeply and intimately; I feel like that level of, I don’t know, is it passion? Expertise? — whatever it is, I feel like it’s missing for me. I tend to be interested in many things on a more shallow level. Like, my friend W. Todd Kaneko has his book, The Dead Wrestler Elegies, which is all intensely focused on pro wrestling. Kiki Petrosino has a huge section in Fort Red Border that’s about an imagined (I assume) affair with Robert Redford; I was inspired by this for my poem in the book “The Poet and the Supermodel (A Rearranged Marriage),” but I was done with the subject in four sections. I tend to be more like that: quickly into and out of a topic. I don’t know, it sort of feels like a failing on my part, some kind of attention deficit or some such. I envy other writers their obsessions. One of my dirty secrets is that I sometimes write in front the television, and the poem I’m working on will come from whatever trashy show is on at the moment I’m writing. I also have a tendency to revisit the pop culture interests of my high school days. Hair band music comes up a lot, for instance, though I’ve put most of those poems in a different manuscript.

UtSQ: If you had to choose, which couple of poems from Ha Ha Ha Thump would you consider your personal favorites? Which characteristics of these poems make them stand (even if only slightly) above the rest for you?

AH: The first one that comes to mind is the last poem in the book, with its way long title: “Ars Poetica Disguised as a Love Poem Disguised as a Commemoration of the 166th Anniversary of the Rescue of the Donner Party.” This poem was partly inspired by Matthew Olzmann’s “Mountain Dew Commercial Disguised as a Love Poem,” and I like to think it achieves what I promise in the title. I might be fooling myself there. I also like the Mick Jagger poem, because it makes me laugh, and because I think it’s out of character for me. (Again, maybe I’m fooling myself.) I read this poem at an AWP offsite event a few years ago, and later in the conference someone said, “Hey, you’re the penis poem guy.” Which is not really how I want to be known, but I’m repeating it here, so maybe part of me does want to be known that way. Was I supposed to answer this question so directly? Or was I supposed to say something about how it would be like choosing a favorite of my children? Because it’s not, really. Oh, and I also have a particular fondness for the Heidi Klum poem and for “She Blinded Me With Molecular Nanotechnology.” These are poems where I think I achieved what I set out to do.

UtSQ: In "Nocturne: Interrogation" you write, "Language is a kind of hunger." Tell us about your first significant literary “hunger.” How did this encounter inspire you, or shape you, into the writer you have become?

AH: One of the things I remember most viscerally about reading as a child — and oh, how I read — was this ache in the back of the throat I would get when I read something that overwhelmed me, this sudden, tangible, physical manifestation of my attachment to the words on the page, the events and characters I was reading about. I remember it most distinctly from books with sad or traumatic endings: Harriet Arnow’s The Dollmaker, Where the Red Fern Grows, The Yearling, Old Yeller, To Kill A Mockingbird — but I also remember it from books in which the character achieves some kind of freedom, or has some great adventure: Treasure Island, Susan Cooper’s The Dark Is Rising series, the Narnia books. I was just in awe of the power of words to get inside me that way, and at some point I became fixated on the idea that I could maybe someday write words that would do that to someone else. I’m still trying.

UtSQ: What was the worst editing or writing advice you have received over the years? What was the best advice you received? Did you follow this advice? Why or why not?

AH: I worked in newspapers for more than a decade, some as a reporter and mostly as an editor, and I worked with a lot of great editors, and a few not-so-great ones. What made the bad ones bad was their desire to impose their own idiosyncrasies onto the text, their unwillingness to listen to the sentence or story in front of them and follow where the language was leading them. This often resulted in silly errors or weirdly awkward sentences in the name of “correctness.” An example: one editor had it in his head that no dialogue tag should ever be “said Jane”; rather it should always be “Jane said.” Now as a rule of thumb, this is fine, but as an absolute? Sometimes the sentence needed to be the other way for reasons of sense or sound or clarity, but this editor would reflexively change it, every time, sometimes ruining a perfectly good sentence in the process. As for how this applies to poetry, I think the same idea is relevant: listen to the sentence; listen to the words; be flexible; don’t force your preconceptions onto a poem. It’s along the lines of what Richard Hugo says in Triggering Town about being willing to let go of the initiating idea of a poem and go where the language takes you. As for the best advice, William Olsen, with whom I worked in grad school at Western Michigan, told me this: “Nothing matters so much to a poem as the state of mind of the poet at the moment of writing.” To me, this means you have to be honest with your readers about why you’re writing something, about what’s at stake for you in the act of creating a poem. Don’t be coy. Don’t hide behind memory, or the alleged factual truth of an experience; instead, be true to the emotional core of the poem. Be willing to be vulnerable on the page. Don’t write to make yourself look smart or moral or emotionally mature. Go for bone. Write the hard stuff, and be honest about why it’s hard.

UtSQ: Finally, Amorak, if you could have a meal with anyone, dead or alive, real or imaginary, whom would it be, and what on earth would the two of you eat?

AH: Jackie Robinson. I read so much about him when I was a kid, and I admire so much what he did for baseball and for American society in general, and I love his spirit, the way he played the game, all fearless and hard-working against unimaginably difficult circumstances. Of course, he was also a world-class athlete, so it’s not like he was getting by simply on guts and hustle. One of my real heroes, and one of the reasons I’m a Dodgers fan. As for what we’d eat, I’ll go with a big greasy pepperoni pizza and Cokes because I’m hungry right now and that sounds delicious.

Amorak Huey is author of the poetry collection Ha Ha Ha Thump (Sundress, 2015) and the chapbook The Insomniac Circus (Hyacinth Girl, 2014). A longtime newspaper editor and reporter, he now teaches writing at Grand Valley State University in Michigan. His poems appear in The Best American Poetry 2012, The Southern Review, The Collagist, Poet Lore, Carolina Quarterly, Quarterly West, and many other journals. Follow him on Twitter: @amorak.