Sally Deskins Interviews Brett Yasko

Pittsburgh-based, nationally known graphic designer Brett Yasko took a go at curating for the first time (and, he said, the last) with John Riegert, at SPACE in Pittsburgh, an exhibition of 252 multi-media and styled portraits by 252 varied-career level Pittsburgh-based artists featuring Riegert, a longtime Pittsburgh artist. As the exhibition is now closed, he is working on a book featuring each portrait, photos of the process and installation, a contribution by John and an essay by Pittsburgh historian Eric Lidji. As a critic who pays attention to critical curatorial display, I took the time to ask Yasko specifically about his curatorial choices and found that while he has perhaps significant ambitions for the concept of the show (to revive Riegert’s career, to experiment showing multi-leveled artists alongside each other, to include the model himself as a live docent during its running), he was not particularly academically thoughtful with regard for didactics or context, but, perhaps unsurprisingly, more concerned with the design and portraying the idea through the display, indirectly providing several layers for contemplation. Here he tells me about putting together this exhibition which took over a year to produce, some of the personal stories behind the works and artists’ relations with the subject, why Riegert is important to recognize, and why he won’t be curating in the future. - SD.

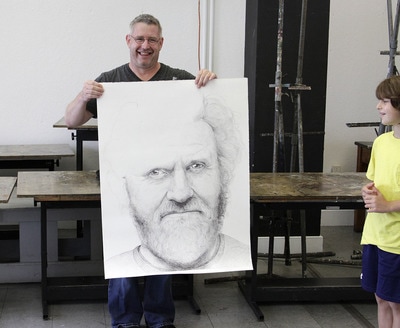

Brett Yasko with John Riegert

Brett Yasko with John Riegert

Sally Deskins: You have been widely recognized for your graphic design both commercially and artistically with projects, exhibitions and publications, and teach at Carnegie Mellon University in the School of Design. Where does curating fit in/why curate?

Brett Yasko: I really don't consider myself a curator in this project. As a designer, I've been fortunate to work with some of the best curators going — not just in Pittsburgh but throughout the country. I know what a curator does. There's research and planning and scholarship and writing. I just came up with an experiment that I wanted to try. And I was lucky that John was up for it. And that all of the artists were up for it. There was a lot of coordinating all the artists who wanted to meet with John and figuring out the logistics of gathering all of the work. And then quickly giving it some order before it was hung. Not to mention all the documentation that I did. And editing the catalogue. But I still bristle when someone says I "curated" this thing. I think of myself more as a "community organizer." And then a documentarian.

SD: So this exhibit is 252 artists’ portraits of Pittsburgh conceptual artist John Riegert, who you’ve known for almost 20 years. You’ve said you wanted to do something experimental by inviting so many different level-artists to participate. But beyond that, what does this exhibition add to the current state of contemporary art? Did you have a model for this exhibit?

BY: I really didn't have a model. In fact, when I had the idea rolling around in my head, I met with a few artists and curators who I trust to see if they had ever heard of anyone doing something like this before. Because if they had, I would have abandoned it. I was inspired by contemporary art — the Carnegie International to be specific. It was there where I discovered the work of Joseph Yoakum and was intrigued by the story of how he became an artist, how he became an artist late in his life, and was self-taught. He didn’t seem to have the typical ambitions of an artist but yet had his own show at the Whitney right before he died. And now here was his work in the International.

Later that evening, I went to the birthday party of my son's friend. And his grandmother gave him a painting that she had done that looked like it could have easily been hung right next to Yoakum's. I asked her if she was influenced by him or had been to the International and she said no. She only started painting a few months earlier in order to make this gift for her grandson.

So while everyone else was eating cake, I started to think about what makes an artist an artist. Why is one person's work in one of the biggest exhibitions in the world, being seen by thousands while someone else's work will sit on a kid's nightstand and only be seen by a few? I wanted to see what would happen if a bunch of artists — known and unknown, at the peak of their career, with the peak yet-to-come or maybe with the peak already behind them — had to make a piece based on the same subject. And what if that subject was a person? And hey, what if that person was part of the show? As a sort of docent. (The artist John Riegert is working as a gallery docent during the show.) So someone would walk in, see all of these portraits of the same person. And then turn around and see that person in the flesh. That sounded really exciting to me. It sounded like something I wanted to try and pull off. But who could the person be? And I immediately thought of John.

Brett Yasko: I really don't consider myself a curator in this project. As a designer, I've been fortunate to work with some of the best curators going — not just in Pittsburgh but throughout the country. I know what a curator does. There's research and planning and scholarship and writing. I just came up with an experiment that I wanted to try. And I was lucky that John was up for it. And that all of the artists were up for it. There was a lot of coordinating all the artists who wanted to meet with John and figuring out the logistics of gathering all of the work. And then quickly giving it some order before it was hung. Not to mention all the documentation that I did. And editing the catalogue. But I still bristle when someone says I "curated" this thing. I think of myself more as a "community organizer." And then a documentarian.

SD: So this exhibit is 252 artists’ portraits of Pittsburgh conceptual artist John Riegert, who you’ve known for almost 20 years. You’ve said you wanted to do something experimental by inviting so many different level-artists to participate. But beyond that, what does this exhibition add to the current state of contemporary art? Did you have a model for this exhibit?

BY: I really didn't have a model. In fact, when I had the idea rolling around in my head, I met with a few artists and curators who I trust to see if they had ever heard of anyone doing something like this before. Because if they had, I would have abandoned it. I was inspired by contemporary art — the Carnegie International to be specific. It was there where I discovered the work of Joseph Yoakum and was intrigued by the story of how he became an artist, how he became an artist late in his life, and was self-taught. He didn’t seem to have the typical ambitions of an artist but yet had his own show at the Whitney right before he died. And now here was his work in the International.

Later that evening, I went to the birthday party of my son's friend. And his grandmother gave him a painting that she had done that looked like it could have easily been hung right next to Yoakum's. I asked her if she was influenced by him or had been to the International and she said no. She only started painting a few months earlier in order to make this gift for her grandson.

So while everyone else was eating cake, I started to think about what makes an artist an artist. Why is one person's work in one of the biggest exhibitions in the world, being seen by thousands while someone else's work will sit on a kid's nightstand and only be seen by a few? I wanted to see what would happen if a bunch of artists — known and unknown, at the peak of their career, with the peak yet-to-come or maybe with the peak already behind them — had to make a piece based on the same subject. And what if that subject was a person? And hey, what if that person was part of the show? As a sort of docent. (The artist John Riegert is working as a gallery docent during the show.) So someone would walk in, see all of these portraits of the same person. And then turn around and see that person in the flesh. That sounded really exciting to me. It sounded like something I wanted to try and pull off. But who could the person be? And I immediately thought of John.

lSD: You also have said you chose John Riegert because of his ability to make artists comfortable, as well as to re-engage Riegert with the artistic community due to a prolonged battle with mental illness. These sound like significant social issues that could have broad implications beyond and along with the idea of the vast amount and variety of portraits. What is the conceptual relationship between Riegert and the works?

BY: Some see this as a commentary on mental health and that's fine. I want people to enter into it however they want and leave with whatever they want or even need. But for me, it's not about mental health or any other particular theme or issue. Mental health is a part of it, though, only because it's part of John's story. As are fatherhood, divorce, friendship, addiction, making art, childhood trauma, an amazing sense of humor and a suicide attempt. The show is about all of these things. But only because they're part of John's story.

I'm not trying to make some grand statement. And the concept is pretty simple. It started out being about John and then it quickly also became about the artists who participated—this community of artists that is Pittsburgh. And I suppose it's also about me and Eric and Julie and Ryan who have been diligently documenting this thing. And also Donna. (She was John's partner. They broke up during the project but are still very close and she was tremendous help coordinating everything). This project really just exploded. I can't think of a project that's been documented as intensely as this project has. Well over 100 artist visits and so much time spent. The Tumblr, the book, the film. But it's been time well-spent. As close as I've felt to John over the years, it's been nothing compared to this past year-and-a-half. Beyond it being a project about John, none of this other stuff was part of the initial design. It just happened that way.

SD: Speaking of the works, what was your curatorial process like? Is there a narrative to the exhibition or is it mostly aesthetic? It looks like you took a salon style approach; was this intentional?

BY: The salon-style hang started out as a matter of necessity. There's just so much work. And much of it I didn't see until a day or two before the install. The invitation to participate was completely open-ended. I didn't put any type of restriction on the artists. So unlike a traditional show where you have measurements of each piece and you can plan and play in SketchUp to decide what works best, I was really working on the fly. We'd work all day and then the crew would leave at 5pm and I'd sit in the gallery just looking at everything. And then I'd start taking things down here and there. So they'd come in the next morning and be like, "Didn't we just hang this yesterday?" I was driving them crazy. But I wanted each placement to have a purpose.

I tried to make relationships between two portraits or a group of portraits. I tried to tell some stories. There's a gallery guide that doesn't describe every single piece but it does give hints. And each portrait is numbered so there is an implied order. One can move through the gallery and devote as much time as they want to discover each story. And engaging with John. Or they can move through quickly and still take something from, if nothing else, the sheer magnitude of work. It's definitely not a traditional show with didactics and every question asked and answered. But like I said, if you're willing to invest enough time in it, you should get something out of it.

SD: Describe a few of the portraits that you placed together and why.

BY: Probably my favorite "cluster" of work centers around the portrait by mixed-media artist Cecilia Ebitz. She met with John last year and wanted him to tell her about an important moment in his life. She would then go back and make a gift inspired by this and bring it back to him. He told her about the miscarriage that he and his now ex-wife went through, and how traumatic it was for him. They were going to name the baby Lily so he planted lilies in the back yard of their house and they still bloom every summer on what would have been her birthday. He also told Cecilia how scared he was when his now ex-wife got pregnant again. But he now has a daughter who he loves very much. So about a year later, Cecilia came back with her gift -- a lily made out of cloth. She gave it to John and he still has it on his desk. She didn't want it in the gallery, she only wanted a photo of him holding it. So I placed that along with the portrait that John's daughter did (she's 12 and, by far, the youngest artist in the show), along with a photo that Christine Holtz took of John and his daughter at his favorite place (a pond in Allegheny Cemetery), and a painting that David Montano made based on a photo he had from almost ten years ago of John holding his daughter. John likes this portrait a lot because he had never seen the photo before.

There's also a cluster of mixed media portraits by Kim Fox, Matthew Newton and Jude Vachon who, when they met with John, shared their own stories of dealing with mental health issues. Kim Fox was someone who John told a story of something horrible that had happened to him as a child that he had never told me and only a few other people know about. So these and so many other portraits represent important stories about John and moments that have greatly impacted his life. And I think on their own, they would still do that. But when they're grouped together it becomes clearer and, I dare say, maybe even more profound.

And there are lighter moments too in terms of groupings. One in particular is a set of portraits by Mark Panza, Kathleen DePasse and David Armbruster. Mark invited us to his studio to draw John and it turned into a live nude drawing session that John really wanted to participate in. So, even though I didn't invite Kathleen and David originally, they said I could add their portraits to the show. Carol Skinger's [pencil on paper] portrait is based on a Tumblr photo documenting the session. These all hang above a [graphite on wood panel] portrait by Kristen Letts Kovak who asked John if she could draw him in the nude in his living room. And above everything are scans of the inside of John's eyes. John Carson was somehow able to arrange this with a doctor he knows. So there's the idea that everyone is looking at John in these portraits and John's own eyes are looking back at them.

BY: Some see this as a commentary on mental health and that's fine. I want people to enter into it however they want and leave with whatever they want or even need. But for me, it's not about mental health or any other particular theme or issue. Mental health is a part of it, though, only because it's part of John's story. As are fatherhood, divorce, friendship, addiction, making art, childhood trauma, an amazing sense of humor and a suicide attempt. The show is about all of these things. But only because they're part of John's story.

I'm not trying to make some grand statement. And the concept is pretty simple. It started out being about John and then it quickly also became about the artists who participated—this community of artists that is Pittsburgh. And I suppose it's also about me and Eric and Julie and Ryan who have been diligently documenting this thing. And also Donna. (She was John's partner. They broke up during the project but are still very close and she was tremendous help coordinating everything). This project really just exploded. I can't think of a project that's been documented as intensely as this project has. Well over 100 artist visits and so much time spent. The Tumblr, the book, the film. But it's been time well-spent. As close as I've felt to John over the years, it's been nothing compared to this past year-and-a-half. Beyond it being a project about John, none of this other stuff was part of the initial design. It just happened that way.

SD: Speaking of the works, what was your curatorial process like? Is there a narrative to the exhibition or is it mostly aesthetic? It looks like you took a salon style approach; was this intentional?

BY: The salon-style hang started out as a matter of necessity. There's just so much work. And much of it I didn't see until a day or two before the install. The invitation to participate was completely open-ended. I didn't put any type of restriction on the artists. So unlike a traditional show where you have measurements of each piece and you can plan and play in SketchUp to decide what works best, I was really working on the fly. We'd work all day and then the crew would leave at 5pm and I'd sit in the gallery just looking at everything. And then I'd start taking things down here and there. So they'd come in the next morning and be like, "Didn't we just hang this yesterday?" I was driving them crazy. But I wanted each placement to have a purpose.

I tried to make relationships between two portraits or a group of portraits. I tried to tell some stories. There's a gallery guide that doesn't describe every single piece but it does give hints. And each portrait is numbered so there is an implied order. One can move through the gallery and devote as much time as they want to discover each story. And engaging with John. Or they can move through quickly and still take something from, if nothing else, the sheer magnitude of work. It's definitely not a traditional show with didactics and every question asked and answered. But like I said, if you're willing to invest enough time in it, you should get something out of it.

SD: Describe a few of the portraits that you placed together and why.

BY: Probably my favorite "cluster" of work centers around the portrait by mixed-media artist Cecilia Ebitz. She met with John last year and wanted him to tell her about an important moment in his life. She would then go back and make a gift inspired by this and bring it back to him. He told her about the miscarriage that he and his now ex-wife went through, and how traumatic it was for him. They were going to name the baby Lily so he planted lilies in the back yard of their house and they still bloom every summer on what would have been her birthday. He also told Cecilia how scared he was when his now ex-wife got pregnant again. But he now has a daughter who he loves very much. So about a year later, Cecilia came back with her gift -- a lily made out of cloth. She gave it to John and he still has it on his desk. She didn't want it in the gallery, she only wanted a photo of him holding it. So I placed that along with the portrait that John's daughter did (she's 12 and, by far, the youngest artist in the show), along with a photo that Christine Holtz took of John and his daughter at his favorite place (a pond in Allegheny Cemetery), and a painting that David Montano made based on a photo he had from almost ten years ago of John holding his daughter. John likes this portrait a lot because he had never seen the photo before.

There's also a cluster of mixed media portraits by Kim Fox, Matthew Newton and Jude Vachon who, when they met with John, shared their own stories of dealing with mental health issues. Kim Fox was someone who John told a story of something horrible that had happened to him as a child that he had never told me and only a few other people know about. So these and so many other portraits represent important stories about John and moments that have greatly impacted his life. And I think on their own, they would still do that. But when they're grouped together it becomes clearer and, I dare say, maybe even more profound.

And there are lighter moments too in terms of groupings. One in particular is a set of portraits by Mark Panza, Kathleen DePasse and David Armbruster. Mark invited us to his studio to draw John and it turned into a live nude drawing session that John really wanted to participate in. So, even though I didn't invite Kathleen and David originally, they said I could add their portraits to the show. Carol Skinger's [pencil on paper] portrait is based on a Tumblr photo documenting the session. These all hang above a [graphite on wood panel] portrait by Kristen Letts Kovak who asked John if she could draw him in the nude in his living room. And above everything are scans of the inside of John's eyes. John Carson was somehow able to arrange this with a doctor he knows. So there's the idea that everyone is looking at John in these portraits and John's own eyes are looking back at them.

SD: As there is the element of Riegert as an individual, I read that there is not informational text available about Riegert in the gallery. This may provoke a response of query as to why so many artists should make portraits of one white guy. So, why didn’t you include information about Riegert, since it seems he is such an important part of this project?

BY: I read that review and it really surprised me because I can't imagine how anyone could devote as much time to the show as I know that particular reviewer did, and still need more information. There are so many portraits that speak implicitly to who John is. Not to mention the fact that John is THERE. For the viewer to ask him whatever they want. Along with a 452-page book that sits right behind his chair and describes almost every minute of the project's year-and-half process And a slide show of over 500 images from that process.

I think anyone wanting — or needing — more information just doesn't understand the idea. This is not "high art." This is not something that needs long text panels to explain or describe what the viewer should be seeing. This is simply an experiment where 252 artists each generously created a portrait of one person. Some met with him one-on-one or as part of a group sitting. Some didn't want to meet with him and worked off a photo I provided. Some worked off of one of the Tumblr photos I posted (talk about a Mobiüs strip). Some knew him already. Some of the portraits are directly representational. Some are abstract and conceptual. Some look like they took a few hours to craft. And some look like they took weeks or even months. Some artists worked in the style that they feel comfortable in. And some saw the invitation as a chance to work in a way they never have before. And I know I'm probably the closest one to this thing and can't at all be objective — but each one is fascinating to me. And, again not being able to be objective, I would challenge anyone to spend more than a few minutes talking with John and then still wonder why all of these artists made these portraits.

This show is about John, of course. But it's also about each of these artists who decided to participate. And it's about the community that these artists are a part of and that John is now back to being a part of. Like I said, answers are there. Someone just needs to take some time to find them.

SD: Why is such self-initiated/independent curating like this important to communities, and specifically for Pittsburgh? Tell me about curating at SPACE and how this was different from your other curating. What does SPACE add to the Pittsburgh conversation, national conversation?

BY: We're lucky to have SPACE in Pittsburgh as well as its director, Murray Horne. I took this idea to the Carnegie Museum of Art and they loved it but said there was no way they could get it passed their lawyers because of the liability. Because it included a live person there was no way they could touch it. No museum would touch it. And so, of course, I asked, "But what about Marina Abramović? What about Ragnar Kjartansson?" And they said all of those types of exhibitions are scripted. They're not "real." And so then I went to Murray and he said "yes" in about 10 seconds. I asked him about the liability and he said, "Screw it." SPACE gives opportunities to curators and artists and even people like me who might not have a lot of experience or a 20-page CV. But they have an idea. And they have a deep desire to carry it through. And Murray recognizes that and allows them to go ahead with it. And the thing that's amazing, at least to me, is 9 out of 10 SPACE shows are shows that I spend a ton of time looking at. They're shows that interest me much more than shows that are at the other museums. SPACE has had some really interesting artists and curators — from all over the world — show work there. I have no idea what that adds to any type of conversation. But I do know that I'm really glad that Pittsburgh has something like it. As a one-time participant, for sure. But also as a constant viewer.

SD: What is next for you curating wise? Would you/do you plan on breaking into New York or other major art scenes, curating?

BY: Oh no. I never want to do anything like this again. I'm very happy to return to my life as a graphic designer. But I'm still involved with extensions of this project. We're working on the catalogue that's going to be an opus. Eric Lidji followed the project almost from the beginning. His "portrait" was an over 256,000-word "essay" that we bound as a book and is in the gallery. But we're in the process now of editing that essay and combining it with my documentation in photos and captions along with shots of each portrait. It's a project almost as big as the show itself.

There's also a filmmaker named Julie Sokolow who's editing a documentary about the project that she has big aspirations for. I'm also working on finding a home for the portraits that artists want to donate to John. The dream is to find a gallery space on the ground floor with an apartment above and have a sort of "John Museum." He'd live there and open it up when he wanted. People could come in and make his portrait and he'd add it to the wall. Or he'd do their portrait or maybe even curate smaller shows. He could also, as the "museum director," sell a portrait which is really fascinating to me. It would be this sort of underground spot that people from all over would have on their list of places they want to see when they come through town. The Carnegie, the Mattress Factory, Wood Street Galleries, The Warhol... and then John.

SD: I have read a little bit about John as an artist, but tell me more about why he is such an important artist to Pittsburgh and beyond, to honor in these ways.

That's not an easy question for me to answer because to fully understand "why John," you really have to meet John. He's the wisest, kindest, bravest guy I know. He's been through a lot and still goes through a lot. But he's working each day to find a way through it. At the opening of the show, someone said that John could very well be the only person in the history of the world that has had this particular experience—all of these terrific artists coming together and surrounding him with all these portraits of him. Does he deserve such an "honor"? Who knows. But we did it. And he has it. And now we just roll on.

---

Brett Yasko is a graphic designer working from a one-person studio in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. His work has been recognized in exhibitions such as the Lodz Design Festival, AIGA 365 and 50 Books, 50 Covers and written about in publications and websites including Communication Arts, Print, How, the New York Times, The Nation, Metropolis, Dwell, Good, Azure, Fast Company, NPR, Design Observer, It’s Nice That, AIGA.org and Pittsburgh’s Post-Gazette, Tribune-Review and City Paper. He occasionally updates his website and looked like this a few years ago. http://brettyasko.com/

BY: I read that review and it really surprised me because I can't imagine how anyone could devote as much time to the show as I know that particular reviewer did, and still need more information. There are so many portraits that speak implicitly to who John is. Not to mention the fact that John is THERE. For the viewer to ask him whatever they want. Along with a 452-page book that sits right behind his chair and describes almost every minute of the project's year-and-half process And a slide show of over 500 images from that process.

I think anyone wanting — or needing — more information just doesn't understand the idea. This is not "high art." This is not something that needs long text panels to explain or describe what the viewer should be seeing. This is simply an experiment where 252 artists each generously created a portrait of one person. Some met with him one-on-one or as part of a group sitting. Some didn't want to meet with him and worked off a photo I provided. Some worked off of one of the Tumblr photos I posted (talk about a Mobiüs strip). Some knew him already. Some of the portraits are directly representational. Some are abstract and conceptual. Some look like they took a few hours to craft. And some look like they took weeks or even months. Some artists worked in the style that they feel comfortable in. And some saw the invitation as a chance to work in a way they never have before. And I know I'm probably the closest one to this thing and can't at all be objective — but each one is fascinating to me. And, again not being able to be objective, I would challenge anyone to spend more than a few minutes talking with John and then still wonder why all of these artists made these portraits.

This show is about John, of course. But it's also about each of these artists who decided to participate. And it's about the community that these artists are a part of and that John is now back to being a part of. Like I said, answers are there. Someone just needs to take some time to find them.

SD: Why is such self-initiated/independent curating like this important to communities, and specifically for Pittsburgh? Tell me about curating at SPACE and how this was different from your other curating. What does SPACE add to the Pittsburgh conversation, national conversation?

BY: We're lucky to have SPACE in Pittsburgh as well as its director, Murray Horne. I took this idea to the Carnegie Museum of Art and they loved it but said there was no way they could get it passed their lawyers because of the liability. Because it included a live person there was no way they could touch it. No museum would touch it. And so, of course, I asked, "But what about Marina Abramović? What about Ragnar Kjartansson?" And they said all of those types of exhibitions are scripted. They're not "real." And so then I went to Murray and he said "yes" in about 10 seconds. I asked him about the liability and he said, "Screw it." SPACE gives opportunities to curators and artists and even people like me who might not have a lot of experience or a 20-page CV. But they have an idea. And they have a deep desire to carry it through. And Murray recognizes that and allows them to go ahead with it. And the thing that's amazing, at least to me, is 9 out of 10 SPACE shows are shows that I spend a ton of time looking at. They're shows that interest me much more than shows that are at the other museums. SPACE has had some really interesting artists and curators — from all over the world — show work there. I have no idea what that adds to any type of conversation. But I do know that I'm really glad that Pittsburgh has something like it. As a one-time participant, for sure. But also as a constant viewer.

SD: What is next for you curating wise? Would you/do you plan on breaking into New York or other major art scenes, curating?

BY: Oh no. I never want to do anything like this again. I'm very happy to return to my life as a graphic designer. But I'm still involved with extensions of this project. We're working on the catalogue that's going to be an opus. Eric Lidji followed the project almost from the beginning. His "portrait" was an over 256,000-word "essay" that we bound as a book and is in the gallery. But we're in the process now of editing that essay and combining it with my documentation in photos and captions along with shots of each portrait. It's a project almost as big as the show itself.

There's also a filmmaker named Julie Sokolow who's editing a documentary about the project that she has big aspirations for. I'm also working on finding a home for the portraits that artists want to donate to John. The dream is to find a gallery space on the ground floor with an apartment above and have a sort of "John Museum." He'd live there and open it up when he wanted. People could come in and make his portrait and he'd add it to the wall. Or he'd do their portrait or maybe even curate smaller shows. He could also, as the "museum director," sell a portrait which is really fascinating to me. It would be this sort of underground spot that people from all over would have on their list of places they want to see when they come through town. The Carnegie, the Mattress Factory, Wood Street Galleries, The Warhol... and then John.

SD: I have read a little bit about John as an artist, but tell me more about why he is such an important artist to Pittsburgh and beyond, to honor in these ways.

That's not an easy question for me to answer because to fully understand "why John," you really have to meet John. He's the wisest, kindest, bravest guy I know. He's been through a lot and still goes through a lot. But he's working each day to find a way through it. At the opening of the show, someone said that John could very well be the only person in the history of the world that has had this particular experience—all of these terrific artists coming together and surrounding him with all these portraits of him. Does he deserve such an "honor"? Who knows. But we did it. And he has it. And now we just roll on.

---

Brett Yasko is a graphic designer working from a one-person studio in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. His work has been recognized in exhibitions such as the Lodz Design Festival, AIGA 365 and 50 Books, 50 Covers and written about in publications and websites including Communication Arts, Print, How, the New York Times, The Nation, Metropolis, Dwell, Good, Azure, Fast Company, NPR, Design Observer, It’s Nice That, AIGA.org and Pittsburgh’s Post-Gazette, Tribune-Review and City Paper. He occasionally updates his website and looked like this a few years ago. http://brettyasko.com/

Sally Deskins is an artist, writer and curator. A recent graduate of the MA program in art history at West Virginia University, Deskins won two awards for her thesis research on the curating of Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party. Her writing has been published in Bitch Magazine, Art on the Banks, n.paradoxa, TRIVIA: Voices of Feminism, Feminist Wire, and Hyperallergic, among others. She edits the online journal Les Femmes Folles, a platform for women in art.