Interview with Jasmine An

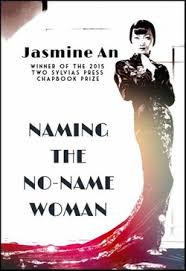

Editor's Note: A "no-name woman" appears in Chinese folklore as a woman shamed and shunned from her community as a result of her lifestyle and choices. Naming the No-Name Woman by Jasmine An modernizes the folktale to center around the first Chinese-American actress, Anna May Wong.

Up the Staircase Quarterly: What drew you toward the initial "no-name woman" and her experience? How did Anna May Wong become the inspiration to incorporate these ideas into your book?

Jasmine An: During the winter of my senior year of college, I finally read Maxine Hong Kingston’s Woman Warrior, which references the character of a “no-name woman” or a woman that “brings shame to the family” and so is forcibly forgotten. I was also writing a lot of academic papers about how experiences of race, gender, and sexuality are passed down through society – a lot of them circling around Chinese-American womanhood with Anna May Wong as a main focal point. I connected her with the idea of a no-name woman because her family and community were disapproving of her career as an actress. Despite their disapproval, she became such a foundational part of Hollywood’s presentation of Asian-Americanness that today she is more of an archetype than an individual, almost more myth than person. Also, like the no-name woman, she endures, she haunts, and try as you might, she does not let you forget.

UtSQ: Many of your poems in Naming the No-Name Woman suggest that the speaker and Anna May Wong's experiences blend. I found your poem "My Father Owned the Sam Kee Laundry in LA" particularly striking. This one blends a modern voice with the slightly more antiquated voice of Anna May Wong:

I graduated from high school in Ann Arbor, Michigan, in 2011.

My boyfriend dragged the sheets from his guest bed and we dropped

them in the laundry on the way out the door every morning before

the sun rose. In 1921, I dropped out of Los Angeles High School.

I died for the first time at age 17. I had a baby with a white man

and drowned when he left me. Then I got up to do it again

the next day I didn’t see him I died again I checked

my texts too many times I sat still while they redid my

makeup I kept looking and looking and looking –

These two voices do not simply become entwined, but from the beginning, seem to be one and the same. Can you speak a little bit about this method? Also, I must ask: How much of the speaker is in Anna May and how much is Anna May in the speaker?

JA: This was one of the first poems I wrote for the collection. I originally started writing the collection with the idea to treat each poem as a game of Two Truths and a Lie: one truth of Anna May Wong, one truth of mine, and a lie. That plan lasted about two poems… but this happens to be one of them. As you say, rather than intertwining two voices, I wanted to make a new speaker out of the truths and lies between the both of us. I honestly can’t say how much of AMW becomes the speaker and how much the speaker becomes AMW – however, the AMW who exists in these poems is almost as fabricated as the speaker. I researched and read, sure, but I have no intimate knowledge or ownership over AMW’s personal life. If anything, my speaker collaborates with the myth of AMW, or one could say her ghostly echo, more than anyone else. So in a way, the speaker, who is absolutely indebted and reliant on AMW for her own existence, simultaneously builds AMW into existence through retelling her legend.

UtSQ: You write largely about the idea of incorporation throughout the book, particularly in the poem "Inheritance", where the speaker physically incorporates the spirit of Anna May Wong: "I open my mouth / and her hands slide out, not elegant, but old, wrinkled palms rubbed / ragged by the years between her death and my birth." A layered metaphor, I found it could also be used to describe how a writer embodies the characters they study and create. What was your process in writing Naming the No-Name Woman? What do you feel you have incorporated from both the real woman’s life that you studied, and the character of your imagination, Anna May Wong? Is she still with you?

JA: Writing this collection was very frenetic. It took place over the course of ten weeks during my last trimester of college. Advanced Poetry with Diane Seuss was a hard class that pushed two poems out of me every week. It was also one of the most self-revelatory times of my life; almost every new poem was some sort of epiphany. AMW made that possible, I think. By writing through her (or at least my imagination of her), I could step outside of myself for a moment, and gain a kind of clarity that wasn’t otherwise possible. While the AMW of my poems is mostly archetypal, the few facts I gained through researching her life were also invaluable details that kept me grounded and lent a historical weight to the project, as well as reaffirming the presence of Asian-American culture and roots in the USA. More than anything else, I think that AMW gives me a sense of legacy, or of having a set of ancestors/ancestry larger even than my blood family that is comforting in the face of self-doubt and anxiety about placing myself in the world. I don’t think she is done with me yet, and I am certainly not willing to consign her to the past.

UtSQ: Death is a recurring theme throughout Naming the No-Name Woman. Death brings the possibility of losing identity—stories never passed down, secrets never revealed. When Anna May Wong died, her secrets died with her. What did you find when you explored the role of physical death alongside identity?

JA: Throughout this whole collection, I was intrigued by the way memories or echoes of a person continue to exist and influence the future, even after physical death. When someone close to us dies, it’s not as if we stop thinking of them. Everything is a constant reminder after a death. I think that can be a beautiful and empowering kind of thing, such as in the case of AMW where I was able to draw inspiration from her even though we were/are alive in different time periods. Her legacy survived her physical death in a powerful way. On the other hand, sometimes it feels like death brings nothing but ugly sorrow and grief upon grief upon grief. Death feels like a particularly overwhelming topic these days so soon after Alton Sterling was killed by the police (Philandro Castile since I began writing this paragraph; countless black folks before them and how many more until this post goes live?), 250 or more were killed in Baghdad during Ramadan and 49 folks were killed in the Pulse shooting in Orlando. While writing these poems, I approached death on my own terms and as an artist. What an unimaginable privilege that was. I don’t think I will be able to see it quite the same way again.

UtSQ: Now let’s jump to the beginning of your writing journey. What was your first significant literary encounter? How did this experience inspire you, or shape you, into the writer you have become?

JA: I think it’s a fairly stock answer for writers to say that they were voracious readers before they became writers, and that is definitely true for me as well. I’m not sure if I can pinpoint a specific significant literary encounter between my mom reading to my siblings and I before bed every night, going to the library with grocery bags and coming home with the entire 15+ books of the Black Stallion series (yeah, I was into horses), or the summer that my sibs and I locked ourselves into the laundry closet and listened to all three books of The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit on CD while doing jigsaw puzzles.

I can say though that my first real foray into writing was when I was about 13 and I decided spontaneously to write a novel about a war between humans and dragons that was somehow supposed to be a metaphor about the U.S. invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq following 9/11. I haven’t touched it in years, but it’s over 100 pages long, still unfinished and still lurking in a folder on my laptop. Though my writing these days is drastically different, I think I still have an enduring love of fantasy/the fantastic and extended metaphor and even though I write poetry, I’m still very grounded in narrative and story arc.

UtSQ: It’s shout out time! Which contemporary writers are your favorites? Which books, besides yours, should we be buying? What in particular about these writers makes them special? What importance and uniqueness do they bring to the literary world?

JA: A couple months ago I read Lo Kwa Mei-en’s The Bees Make Money in the Lion. I went into the book not knowing much about it. I’d seen it on Heavy Feather Review’s list of titles they were looking for reviewers for, and I was intrigued. After reading it, I am in absolute awe of Lo Kwa Mei-en’s dexterity with language, her indomitable sense of sound and rhyme, and the fearlessness of her poems. I highly recommend this book to everyone, especially if you are interested in the possibilities of writing in form and stretching language to the limit.

Another fairly new poet to me who I am absolutely in love with is Nandini Dhar. I’m inspired by her willingness to step into myth and world build and embrace the surreal so completely that it becomes the mundane and make the mundane so surreal that it’s no longer apparent which is which. I love the way she manipulates narrative and how often I find myself shocked by a twist or revealing of a sudden truth in her poems. Also, her imagery is so weird and wired, specific and beautifully vivid. I really can’t wait to read more of her poems.

UtSQ: Finally, Jasmine, if you could have a meal with anyone, dead or alive, real or imaginary, whom would it be, what would you talk about, and what on earth would the two of you eat?

JA: To be honest, if I could choose anyone right now, I’d eat a meal with my fam. I’m currently living on the other side of the world from them, and while it’s great, it’d also be great to indulge in the family habit of ordering Dominos pizza much too frequently while watching soccer in the living room.

About Jasmine An

JASMINE AN is a queer, third generation Chinese-American who comes from the Midwest. A 2015 graduate of Kalamazoo College, she has also lived in New York City and Chiang Mai, Thailand, studying poetry, urban development, and blacksmithing. Her first chapbook, Naming the No-Name Woman (2016), was selected as the winner of the 2015 Two Sylvias Press Chapbook Prize. Her poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in HEArt Online, Stirring, Heavy Feather Review, and Southern Humanities Review. Her soulmate and forever muse is Sun Wukong, the Monkey King. Currently, she can be found in Chiang Mai continuing her study of the Thai language.

JA: Throughout this whole collection, I was intrigued by the way memories or echoes of a person continue to exist and influence the future, even after physical death. When someone close to us dies, it’s not as if we stop thinking of them. Everything is a constant reminder after a death. I think that can be a beautiful and empowering kind of thing, such as in the case of AMW where I was able to draw inspiration from her even though we were/are alive in different time periods. Her legacy survived her physical death in a powerful way. On the other hand, sometimes it feels like death brings nothing but ugly sorrow and grief upon grief upon grief. Death feels like a particularly overwhelming topic these days so soon after Alton Sterling was killed by the police (Philandro Castile since I began writing this paragraph; countless black folks before them and how many more until this post goes live?), 250 or more were killed in Baghdad during Ramadan and 49 folks were killed in the Pulse shooting in Orlando. While writing these poems, I approached death on my own terms and as an artist. What an unimaginable privilege that was. I don’t think I will be able to see it quite the same way again.

UtSQ: Now let’s jump to the beginning of your writing journey. What was your first significant literary encounter? How did this experience inspire you, or shape you, into the writer you have become?

JA: I think it’s a fairly stock answer for writers to say that they were voracious readers before they became writers, and that is definitely true for me as well. I’m not sure if I can pinpoint a specific significant literary encounter between my mom reading to my siblings and I before bed every night, going to the library with grocery bags and coming home with the entire 15+ books of the Black Stallion series (yeah, I was into horses), or the summer that my sibs and I locked ourselves into the laundry closet and listened to all three books of The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit on CD while doing jigsaw puzzles.

I can say though that my first real foray into writing was when I was about 13 and I decided spontaneously to write a novel about a war between humans and dragons that was somehow supposed to be a metaphor about the U.S. invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq following 9/11. I haven’t touched it in years, but it’s over 100 pages long, still unfinished and still lurking in a folder on my laptop. Though my writing these days is drastically different, I think I still have an enduring love of fantasy/the fantastic and extended metaphor and even though I write poetry, I’m still very grounded in narrative and story arc.

UtSQ: It’s shout out time! Which contemporary writers are your favorites? Which books, besides yours, should we be buying? What in particular about these writers makes them special? What importance and uniqueness do they bring to the literary world?

JA: A couple months ago I read Lo Kwa Mei-en’s The Bees Make Money in the Lion. I went into the book not knowing much about it. I’d seen it on Heavy Feather Review’s list of titles they were looking for reviewers for, and I was intrigued. After reading it, I am in absolute awe of Lo Kwa Mei-en’s dexterity with language, her indomitable sense of sound and rhyme, and the fearlessness of her poems. I highly recommend this book to everyone, especially if you are interested in the possibilities of writing in form and stretching language to the limit.

Another fairly new poet to me who I am absolutely in love with is Nandini Dhar. I’m inspired by her willingness to step into myth and world build and embrace the surreal so completely that it becomes the mundane and make the mundane so surreal that it’s no longer apparent which is which. I love the way she manipulates narrative and how often I find myself shocked by a twist or revealing of a sudden truth in her poems. Also, her imagery is so weird and wired, specific and beautifully vivid. I really can’t wait to read more of her poems.

UtSQ: Finally, Jasmine, if you could have a meal with anyone, dead or alive, real or imaginary, whom would it be, what would you talk about, and what on earth would the two of you eat?

JA: To be honest, if I could choose anyone right now, I’d eat a meal with my fam. I’m currently living on the other side of the world from them, and while it’s great, it’d also be great to indulge in the family habit of ordering Dominos pizza much too frequently while watching soccer in the living room.

About Jasmine An

JASMINE AN is a queer, third generation Chinese-American who comes from the Midwest. A 2015 graduate of Kalamazoo College, she has also lived in New York City and Chiang Mai, Thailand, studying poetry, urban development, and blacksmithing. Her first chapbook, Naming the No-Name Woman (2016), was selected as the winner of the 2015 Two Sylvias Press Chapbook Prize. Her poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in HEArt Online, Stirring, Heavy Feather Review, and Southern Humanities Review. Her soulmate and forever muse is Sun Wukong, the Monkey King. Currently, she can be found in Chiang Mai continuing her study of the Thai language.