An Interview with Laura Madeline Wiseman

Up the Staircase Quarterly: Let’s get right to the nitty-gritty, Laura Madeline Wiseman. Your book, The Hunger of the Cheeky Sisters: Ten Tales (Les Femmes Folles Books 2015) explores girlhood, femininity, sexuality, poverty, familial relationships, eating disorders, and many other topics in an intimate second-person prose style. While reading, I felt like I was peeking into a diary. What was your writing process for this book? What inspired you to deviate from poetry and create a collection in the vein of a memoir?

Laura Madeline Wiseman: You’re right. I’m a deviator. In Ph.D. school I focused on poetry and wrote the dissertation that became the book Queen of the Platform(Anaphora Literary Press, 2013), a sequence of poems that explores the life of the suffragist Matilda Fletcher, my great-great-great-grandmother. One summer, I took American short fiction and drafted “Fish and Girls.” One spring, I took a master class with Tim O’Brien. Another two summers, I took two mini-master classes on prose, one with Judith Kitchen and another with Stephen King’s son—though the son’s wife became ill, he canceled the class, and sent feedback and apologies.

Laura Madeline Wiseman: You’re right. I’m a deviator. In Ph.D. school I focused on poetry and wrote the dissertation that became the book Queen of the Platform(Anaphora Literary Press, 2013), a sequence of poems that explores the life of the suffragist Matilda Fletcher, my great-great-great-grandmother. One summer, I took American short fiction and drafted “Fish and Girls.” One spring, I took a master class with Tim O’Brien. Another two summers, I took two mini-master classes on prose, one with Judith Kitchen and another with Stephen King’s son—though the son’s wife became ill, he canceled the class, and sent feedback and apologies.

One fall, I took Native American Eco-Feminism and wrote “How to Kill Butterflies,” a creative response to a book on women and animals. I wrote “How to Measure Your Breast Size” while pursuing a M.A. in women’s studies. “From Russia with Love US” was inspired by a study abroad lead by faculty at UNL where I teach. Maybe I’m really a fiction writer in poet’s garb. Or perhaps a wannabe artist with bad handwriting. When the artist Lauren Rinaldi and I began collaborating on Tales, we noticed that both her art and my prose explored themes on girlhood, coming of age, and the body. Though the stories were written over a ten-year period, they weren’t a book until we began collaborating—creating art (Lauren) and revising, reshaping, sequencing (me).

UtSQ: There is a definitive evolution from girlhood to womanhood in Tales, all the while using “hunger” as both a metaphor and a literal need. What does hunger mean for you, personally? What do you hope your readers take away from this work?

UtSQ: There is a definitive evolution from girlhood to womanhood in Tales, all the while using “hunger” as both a metaphor and a literal need. What does hunger mean for you, personally? What do you hope your readers take away from this work?

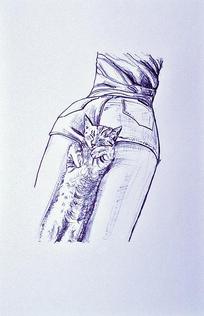

illustration by Lauren Rinaldi

illustration by Lauren Rinaldi

LMW: I am hungry. As a girl, I was hungry to learn, hungry for experience, hungry as I tried to measure my body against the body expectations society suggests women and girls should follow. As I went through school, I was hungry to understand, hungry to travel, hungry because healthy food is expensive and student wages are meager. After I graduated, I was hungry to write, hungry to read, hungry because I long-distance bicycle for fun and training requires fuel. Now, I’m hungry because it’s almost dinner and I biked forty miles before lunch.

UtSQ: The artwork and illustrations in Tales are stunning and multifaceted: sexy, innocent, grotesque, and well, cheeky. How did the collaboration with artist Lauren Rinaldi occur? Were the tales and the artwork created simultaneously, or did one medium come before the other? What do you feel Rinaldi’s artwork brings to your words? (View more of Featured Artist Lauren Rinaldi's work HERE.)

LMW: The collaboration occurred online. I met Lauren in person the first time in Philadelphia this March. The gallery that represents her work, Paradigm Gallery + Studio, hosted a reading and show. I was nervous to meet her. When I entered, I hunkered down in my coat and shadowed my eyes under the brim of my cap. I sidled around the gallery, hungry to see. My skin tingled. I barely breathed. I knew the art in Tales well, but to see it in person, I felt my belly drop. Some of the paintings were larger than I imagined, some smaller. Her “Cheeky Sketches” were displayed behind the microphone by twine and clothespins. When she walked over to me, I hugged her. I gushed. I said all the silly nervous things people say and then I said, Thank you for collaborating with me.

For Tales, some of the art was created new for the book, some of the stories were revised heavily to resonate more closely with the art. Some art and stories weren’t changed at all, given how closely aligned they were in theme.

UtSQ: Several types of relationships are explored in Tales. You highlight an intriguing mother-daughter dynamic, as well as father-daughter, sisters, friendships, and lovers. Although you delve into the heart of many of these relationships, the reader is still left with a feeling of oneness and of the self. Your narrator is very much alone but rarely speaks of loneliness. Was this an intentional direction you took with the project, or was it simply a natural occurrence?

LMW: That’s provocative. I hadn’t thought about loneliness. I grew up with lots of sisters and my mother was a military brat in a family of nine. As a writer, I value solitude. Fellowships, residencies, offices with doors that lock are gifts. This weekend morning, I biked, stretched, and have been in my office on campus ever since. Downtown traffic murmurs. The building’s air system purrs. Other students and faculty come and go, but we all keep to silence. Do I feel alone? I feel privileged. I have a mini-fridge full of food, a kettle to make mugs of hot tea, a restroom down the hall, internet, a printer, a wide view of the city as it slopes towards Antelope Creek. In the distance, windmills generate electricity and the trees everywhere are beginning to bud. Sometimes, I watch pigeons and blackbirds run the sky. I’m not sure what others need to feel full, satiated, content, but hours of silence to work alone fill me in ways no other single thing can. Perhaps there’s a little bit of me in the girls in the book, for certainly being alone to work is one my life’s greatest pleasures.

UtSQ: Another collection of yours, American Galactic (Martian Lit Books 2014) is an imaginative, witty, and compelling book of poetry themed on Martians. Much of the work is amusing, but there are also poems in this collection that are gorgeously vulnerable and sincere. Now, I must ask you first, why on earth Martians? Secondly, why didn’t I think of that?

LMW: I started writing the poems spontaneously. I took a master poetry class with Naomi Shihab Nye and Martians walked into my poetry. It was a spring of storms, power lines down, men with flashlights in the dark of night walking the fence line to climb poles and reconnect what had fallen. I also grew up watching and reading sci-fi and fantasy. I’m actually not sure what took Martians so long to land in my poetry, but I’m glad they did.

As for you, well, I’ve often found that a character or characters won’t leave me alone until they’re done with me and then, just as suddenly as they arrive, they leave. Maybe Martians will knock on your door next. Question is, will you open up and let the Martians inside? Or will you run upstairs, push the dresser in front of the door, and slide into your closet to call 911?

UtSQ: The artwork and illustrations in Tales are stunning and multifaceted: sexy, innocent, grotesque, and well, cheeky. How did the collaboration with artist Lauren Rinaldi occur? Were the tales and the artwork created simultaneously, or did one medium come before the other? What do you feel Rinaldi’s artwork brings to your words? (View more of Featured Artist Lauren Rinaldi's work HERE.)

LMW: The collaboration occurred online. I met Lauren in person the first time in Philadelphia this March. The gallery that represents her work, Paradigm Gallery + Studio, hosted a reading and show. I was nervous to meet her. When I entered, I hunkered down in my coat and shadowed my eyes under the brim of my cap. I sidled around the gallery, hungry to see. My skin tingled. I barely breathed. I knew the art in Tales well, but to see it in person, I felt my belly drop. Some of the paintings were larger than I imagined, some smaller. Her “Cheeky Sketches” were displayed behind the microphone by twine and clothespins. When she walked over to me, I hugged her. I gushed. I said all the silly nervous things people say and then I said, Thank you for collaborating with me.

For Tales, some of the art was created new for the book, some of the stories were revised heavily to resonate more closely with the art. Some art and stories weren’t changed at all, given how closely aligned they were in theme.

UtSQ: Several types of relationships are explored in Tales. You highlight an intriguing mother-daughter dynamic, as well as father-daughter, sisters, friendships, and lovers. Although you delve into the heart of many of these relationships, the reader is still left with a feeling of oneness and of the self. Your narrator is very much alone but rarely speaks of loneliness. Was this an intentional direction you took with the project, or was it simply a natural occurrence?

LMW: That’s provocative. I hadn’t thought about loneliness. I grew up with lots of sisters and my mother was a military brat in a family of nine. As a writer, I value solitude. Fellowships, residencies, offices with doors that lock are gifts. This weekend morning, I biked, stretched, and have been in my office on campus ever since. Downtown traffic murmurs. The building’s air system purrs. Other students and faculty come and go, but we all keep to silence. Do I feel alone? I feel privileged. I have a mini-fridge full of food, a kettle to make mugs of hot tea, a restroom down the hall, internet, a printer, a wide view of the city as it slopes towards Antelope Creek. In the distance, windmills generate electricity and the trees everywhere are beginning to bud. Sometimes, I watch pigeons and blackbirds run the sky. I’m not sure what others need to feel full, satiated, content, but hours of silence to work alone fill me in ways no other single thing can. Perhaps there’s a little bit of me in the girls in the book, for certainly being alone to work is one my life’s greatest pleasures.

UtSQ: Another collection of yours, American Galactic (Martian Lit Books 2014) is an imaginative, witty, and compelling book of poetry themed on Martians. Much of the work is amusing, but there are also poems in this collection that are gorgeously vulnerable and sincere. Now, I must ask you first, why on earth Martians? Secondly, why didn’t I think of that?

LMW: I started writing the poems spontaneously. I took a master poetry class with Naomi Shihab Nye and Martians walked into my poetry. It was a spring of storms, power lines down, men with flashlights in the dark of night walking the fence line to climb poles and reconnect what had fallen. I also grew up watching and reading sci-fi and fantasy. I’m actually not sure what took Martians so long to land in my poetry, but I’m glad they did.

As for you, well, I’ve often found that a character or characters won’t leave me alone until they’re done with me and then, just as suddenly as they arrive, they leave. Maybe Martians will knock on your door next. Question is, will you open up and let the Martians inside? Or will you run upstairs, push the dresser in front of the door, and slide into your closet to call 911?

UtSQ: What resources did you turn to during your writing of American Galactic? Were there specific books, songs, movies, articles, or TV shows that inspired you? Also, are you a fan of The X-Files? I heard they are bringing that show back.

LMW: I researched Mars—science, history, lore, literature, fact. I reread The Martian Chronicles and taught it in my introduction to literature class. My best friend is a movie/TV junkie and with only the slightest coaxing will watching anything. “Hey,” I might say, “Do you want to do a weekend marathon of sci-fi--Enemy Mine, Total Recall, War of the Worlds, Star Wars, Star Trek: The Next Generation?” His answer is always yes. He’ll even make the popcorn. When X-Files was on television, I wasn’t much watching TV then. I’ve gone through phases of little to none, to gluttonous TV/film consumption, but my baby sister is an X-Files fan and so is my aunt. She even named her dog Scully. When I’m writing a sequence of poems, I tend to let obsession find me. After American Galactic was accepted, but before it was released, I was in New Mexico on fellowship and delighted in the UFO stickers on cattle crossing signs, the alien imagery in Roswell, and the otherworldly landscape of the southwest.

UtSQ: Both The Hunger of the Cheeky Sisters and American Galactic focus closely on very pronounced themes, along with many of your other books. Have themes always been an influential aspect of your writing process? What have been your favorite themes to study and immerse yourself in?

LMW: Themes favor me—mermaids, suffragist ancestors, bras, Martians, Cleopatra, advertising, gender violence, imaginary body parts, bluebeard, Lilith, the lady of death, monsters, ghosts, messages in bottles, substance abuse, hunger, the body—and they’re all favorite, or maybe I’m theirs.

UtSQ: Tell us about your first significant literary encounter. How did this experience inspire you, or shape you, into the writer you have become?

LMW: Would a recent literary encounter be okay? A few weeks after American Galactic was released, I got into my car and drove to the starting town for a seven-day bike ride across Iowa. It was the second year I’ve participated in this ride, one that is annually over 400 miles long and several thousand riders strong. The shenanigans and festive fun intoxicate. My team adopted a Martian as a mascot. Each day as we biked the fifty plus miles, one of us carried the mascot—a small green stuffy alien that I bought at a UFO shop in Roswell, near the International UFO Museum and Research Center. Unless you’re Lance Armstrong, most people on the ride are normal type people who have normal type jobs and pursue normal type daily lives, except they choose to spend their summer vacation on their bike, camping, and waiting in lines to take a shower. Everyone is nobody. We’re all pairs and trios and teams of nobodies. It’s like a fair or a parade. We’re all in costumes, some literary so—super heroes, tutus, team helmets with mascots zip-tied to the crowns. Most of us wear spandex, cycling shorts, jerseys from previous rides, helmets, shoes, wraparound sunglasses, gloves, clips. Everyone sweats. I sunburn. Lots of us use the facilities of cornfields. Strangers talk to you, say hello. Cyclists passed by and shout one-liners, small talk, joke. Our Martian received lots of banter. One passerby told us it was there, on our bike bag, swaying with the miles. One called, Psst an alien is attacking you. Another said, The bike band is a nice touch--for we’d saved the trim from our wristband and attached it to the mascot’s stuffy arm—but what was most startling to me was how something as innocuous as a vacation souvenir from Roswell purchased on whim in anticipation of the book, offered space to converse, a way to say, even though we’re talking about aliens here, we’re all on this ride together and you’re one of us.

UtSQ: What is next for you? What projects are you currently working on? What’s in the pipeline?

LMW: I’m too shy to say. Is that okay? I’m obsessed and having fun.

UtSQ: Finally, Madeline, if you could have a meal with anyone, dead or alive, real or imaginary, who would it be, and what on earth would the two of you eat?

LMW: Matilda Fletcher. We would have coffee, sweet and creamy. She would eat pie before her meal and I would eat the meal, skipping the pie. It would take place in the house in Sherman Hill in Des Moines where she lived, but has since been razed. In its place is an apartment complex with numbered doors that open onto a busy intersection with roads that take one to the hospital, to the interstate, to houses build when she still lived, and to the cemetery where she’s buried with her daughter and two husbands, everyone but her in unmarked graves.

Laura Madeline Wiseman is the author of twenty books and chapbooks and the editor of Women Write Resistance: Poets Resist Gender Violence (Hyacinth Girl Press). Her recent books are Drink (BlazeVOX Books), Wake (Aldrich Press), Some Fatal Effects of Curiosity and Disobedience (Lavender Ink), The Bottle Opener (Red Dashboard), and the collaborative book The Hunger of the Cheeky Sisters (Les Femmes Folles) with artist Lauren Rinaldi. Her work has appeared in Prairie Schooner, Margie, Mid-American Review, Ploughshares, and Calyx.

LMW: I researched Mars—science, history, lore, literature, fact. I reread The Martian Chronicles and taught it in my introduction to literature class. My best friend is a movie/TV junkie and with only the slightest coaxing will watching anything. “Hey,” I might say, “Do you want to do a weekend marathon of sci-fi--Enemy Mine, Total Recall, War of the Worlds, Star Wars, Star Trek: The Next Generation?” His answer is always yes. He’ll even make the popcorn. When X-Files was on television, I wasn’t much watching TV then. I’ve gone through phases of little to none, to gluttonous TV/film consumption, but my baby sister is an X-Files fan and so is my aunt. She even named her dog Scully. When I’m writing a sequence of poems, I tend to let obsession find me. After American Galactic was accepted, but before it was released, I was in New Mexico on fellowship and delighted in the UFO stickers on cattle crossing signs, the alien imagery in Roswell, and the otherworldly landscape of the southwest.

UtSQ: Both The Hunger of the Cheeky Sisters and American Galactic focus closely on very pronounced themes, along with many of your other books. Have themes always been an influential aspect of your writing process? What have been your favorite themes to study and immerse yourself in?

LMW: Themes favor me—mermaids, suffragist ancestors, bras, Martians, Cleopatra, advertising, gender violence, imaginary body parts, bluebeard, Lilith, the lady of death, monsters, ghosts, messages in bottles, substance abuse, hunger, the body—and they’re all favorite, or maybe I’m theirs.

UtSQ: Tell us about your first significant literary encounter. How did this experience inspire you, or shape you, into the writer you have become?

LMW: Would a recent literary encounter be okay? A few weeks after American Galactic was released, I got into my car and drove to the starting town for a seven-day bike ride across Iowa. It was the second year I’ve participated in this ride, one that is annually over 400 miles long and several thousand riders strong. The shenanigans and festive fun intoxicate. My team adopted a Martian as a mascot. Each day as we biked the fifty plus miles, one of us carried the mascot—a small green stuffy alien that I bought at a UFO shop in Roswell, near the International UFO Museum and Research Center. Unless you’re Lance Armstrong, most people on the ride are normal type people who have normal type jobs and pursue normal type daily lives, except they choose to spend their summer vacation on their bike, camping, and waiting in lines to take a shower. Everyone is nobody. We’re all pairs and trios and teams of nobodies. It’s like a fair or a parade. We’re all in costumes, some literary so—super heroes, tutus, team helmets with mascots zip-tied to the crowns. Most of us wear spandex, cycling shorts, jerseys from previous rides, helmets, shoes, wraparound sunglasses, gloves, clips. Everyone sweats. I sunburn. Lots of us use the facilities of cornfields. Strangers talk to you, say hello. Cyclists passed by and shout one-liners, small talk, joke. Our Martian received lots of banter. One passerby told us it was there, on our bike bag, swaying with the miles. One called, Psst an alien is attacking you. Another said, The bike band is a nice touch--for we’d saved the trim from our wristband and attached it to the mascot’s stuffy arm—but what was most startling to me was how something as innocuous as a vacation souvenir from Roswell purchased on whim in anticipation of the book, offered space to converse, a way to say, even though we’re talking about aliens here, we’re all on this ride together and you’re one of us.

UtSQ: What is next for you? What projects are you currently working on? What’s in the pipeline?

LMW: I’m too shy to say. Is that okay? I’m obsessed and having fun.

UtSQ: Finally, Madeline, if you could have a meal with anyone, dead or alive, real or imaginary, who would it be, and what on earth would the two of you eat?

LMW: Matilda Fletcher. We would have coffee, sweet and creamy. She would eat pie before her meal and I would eat the meal, skipping the pie. It would take place in the house in Sherman Hill in Des Moines where she lived, but has since been razed. In its place is an apartment complex with numbered doors that open onto a busy intersection with roads that take one to the hospital, to the interstate, to houses build when she still lived, and to the cemetery where she’s buried with her daughter and two husbands, everyone but her in unmarked graves.

Laura Madeline Wiseman is the author of twenty books and chapbooks and the editor of Women Write Resistance: Poets Resist Gender Violence (Hyacinth Girl Press). Her recent books are Drink (BlazeVOX Books), Wake (Aldrich Press), Some Fatal Effects of Curiosity and Disobedience (Lavender Ink), The Bottle Opener (Red Dashboard), and the collaborative book The Hunger of the Cheeky Sisters (Les Femmes Folles) with artist Lauren Rinaldi. Her work has appeared in Prairie Schooner, Margie, Mid-American Review, Ploughshares, and Calyx.