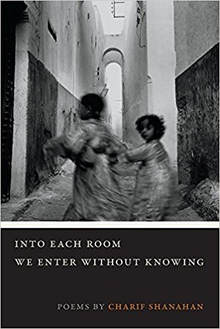

Into Each Room We Enter without Knowing by Charif Shanahan

Paperback: 78 pages

Publisher: Crab Orchard Series in Poetry (Southern Illinois University Press, 2017)

Purchase @ Southern Illinois University Press

Reviewed by Margaret Stawowy.

In the last issue of UtSQ (Issue #37), I reviewed Safia Elhillo’s book The January Children. This issue’s review links to many of the themes of Elhillo’s book. In fact, there is an epistolary poem addressed to Elhillo in Charif Shanahan’s award-winning book Into Each Room We Enter without Knowing (Crab Orchard Series in Poetry—First Book Award).

Similar to Elhillo, Shanahan’s work explores issues of race, family, culture, and love in all its complexities and contradictions. Separated into four sections, the book traverses Shanahan’s physical/emotional landscapes in America, Africa, and Europe. Shanahan, well-traveled, finds that regardless of country, the search for identity remains elusive; connection with the wider world, equally elusive.

In “Soho (London)”:

. . .I don’t tell you

when I pass the club teeming

with men in glitter I am

full of lust

and pity: I want us

to put our clothes back on and go

I think I am close

when I pass a stranger

and think

I could love you. . .

There is a visceral energy to Shanahan’s poems, where he finds himself in constant negotiation with physical longing, authenticity of self, and an uncompromising sense of the dignity of others. In “Briefs” Shanahan navigates this terrain without apology. The speaker listens in as his philandering one-night stand lies to his wife on the phone, thinking “who’s he trying to fool?” and then pondering how the cheated woman must feel. In “Bronze Parrot” Shanahan looks back to defining moments in his past:

. . .as when I heard the crash that took my other life, as when that man

in me who’s not me but has a voice like mine rang the schoolyard bell

like the nuns who grabbed and dragged me by the collar, when that man

inside, first voiceless, first began to grow, when the men around me began

to gleam with some kind of holy spark I wanted to swallow--

Shanahan’s intimations and vulnerabilities spontaneously combust off the page, singing the reader with the kind of burn that is necessary to benefit the ecosystem of heart and mind. When documenting his contradictions or the world’s contradictions, he guides the reader into an evolving landscape where justice and respect are not guaranteed.

Similarly, when addressing racial identity, Shanahan plunges into jagged realities, beginning with apt titles, such as, “Wanting to be White," "'A Mouthful of Salt.../ I Came through Numb Waters,'” “Unbearable White,” and “At L’Express Bistro My White Father Kisses My Black Mother then Calls the Waiter a Nigger.” In that poem:

“Mom says, Tell me how you feel.

These days, I mutter, black. Quite black. Pass the cream.”

Further, in “Clean Slate,” a speaker recounts an incident where his mother drank a glass of bleach and survived, a possible metaphor for her denial of race and ethnicity. In the concluding lines of that poem, he tells her: I’m beginning to understand that I am African. And she said, Now how can that be child? How can that be?

How can it not be?

Throughout this collection, Shanahan shoulders the legacies of racist attitudes spanning the two continents of his parentage. On the American side, he often conveys white supremacy and everyday racism as crude, bigoted remarks in cringe-worthy detail. On the African side, Shanahan addresses how dark-skinned Arabs in Africa, like his mother, are often regarded as inferior--and painfully, how they, like the speaker's mother, often defend the system that oppresses them.

Section IV contains an eight page poem “Your Foot, Your Root,” in which the speaker attempts to extract an explanation from his father for years of his rough, hurtful language:

. . .how could you say the things you said

all my life, those things you said you know which ones I

mean?

To which his father gives a nearly non-sequitur reply:

“Listen—I’ve known plenty of white niggers in my day, too.”

These poems are brilliant in their unrelenting examination of the personal, political, and historical that converge into the unique circumstances of Shanahan’s existence. His use of language to describe the uncomfortable, the disturbing, the unjust, is all the more powerful for his composed and nearly calm observation. Even carefully chosen omissions hover over the page creating more impact via their absence than presence.

Shanahan closes this volume with the poem “Whiteness on Her Deathbed,” a study of the speaker's deceased mother’s physical remains as he performs a last rite of cleansing with water, linen and finally, words to come to terms with all he can never rectify or know.

Charif Shanahan was born in the Bronx in 1983 to an Irish-American father and a Moroccan mother. He holds an MFA in poetry from New York University. His poems have appeared in Baffler, Boston Review, Callaloo, Literary Hub, New Republic, Poetry International, Prairie Schooner, and elsewhere. He has received awards and fellowships from the Academy of American Poets, Cave Canem, the Frost Place, the Fulbright Program, the Millay Colony for the Arts, and Stanford University, where he is a Wallace Stegner Fellow in Poetry.