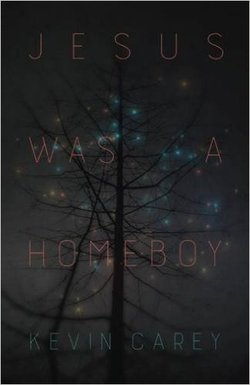

Paperback: 80 pages

Publisher: Cavan Kerry Press, LTD. (2016)

Purchase: www.cavankerrypress.org

Review by Jennifer Martelli

Kevin Carey invokes Dali’s painting “Persistence of Memory” when he writes:

If Dali were here, I would ask

him to stop his clocks from melting,

maybe catch the drippings

in a bucket, something we could

use later to recycle the minutes

that race past us like a bullet train.

(“Chicago”)

In his second poetry collection, Jesus Was a Homeboy, Carey examines the tension between the grief of things lost to the past and the repetition of that past. Carey’s poems are as clear as the ocean, and like the tides, his poems move with rhythmic control, pulled by forces sometimes out of the speaker’s control.

I should be a father

of young children forever . . . . standing in deep dug

holes at the beach.

But time never listens.

(“Delayed”)

With one foot firmly planted in the past and another in the present, Carey spans worlds with poems moving back and forth from childhood, to the present, and sometimes, to the future. Imagine standing at the shore, experiencing the rush of the waves and then the pull of a whole ocean as the tide recedes. In his poem “Looking at an Old Man in the Pleasant Street Tea Room,” the speaker imagines his mother, who suffers from Alzheimer’s (a disease of constant past, where time becomes irrelevant) reunited with his father, who died years earlier:

Maybe she is already there,

one foot in the water

connecting to that place . . . .

. . . . where everything we remember

is just happening.

The image of hands reaching across, spanning--Bill Russell’s huge hands or a young boy’s hands palming a basketball--repeat throughout the book. In “Things I’ve Lost,” after listing lost objects, Carey ends the poem with “. . . . I’m reaching out with both hands/trying to pull the day back from where it came.” In “My Father’s Son,” as the speaker holds the telephone while arguing with his son, the distance seems too far to span, and the roles become blurred, watery.

. . . . we are a thousand miles

apart, acting in unison,

a conversation ending without words.

. . . . but I am my father now,

praying in empty churches

knees aching,

the clouds gray and hanging over my head.

Storms are another image woven throughout Jesus Was a Homeboy. If you’ve lived by a beach (as both Kevin Carey and I have), you’ll know there is a distinct electric menace to a storm approaching. The storms in Carey’s collection are harbingers of memory. In “Summer Storms,” Carey opens with “They haunt me,/these people.” He continues the exploration of memory as the storm begins:

heaving drops of summer

pounding the pavement

washing away the heat,

some of the memories I can’t face.

The sky flashes and I think

When did the lightning start to scare me?

What makes these storms so anxiety-provoking is the speaker’s knowledge that they are there, inevitable, like memory and change. In “Another Coffee Shop,” Carey writes, “Nothing ever stays the same, does it?/Some disruption is always lurking,/like the first crack of thunder.”

Movies--home movies, cinema--provide safety, a way to control this rush of memory, or at least give an illusion of control. In perhaps one of the most beautiful poems in the collection, “Home Movie,” Carey describes old “16-millimeter footage” of himself and his father in a small boat:

. . . . All he had to do

was look across to know I was safe,

no secrets, no worry, no phone calls at 3 a.m.

I can see it on his face, his whole life slowed down,

no future, no regrets, just the summer

for one long moment, the oars, my hand dipping

into the cool dark water around us . . . .

Watching movies also provides a way to examine a life, to observe the love and pain from a distance. In the longest poem in the collection, “Motion Picture Family,” Carey states “we are a family who needs our films,” and that his “. . . .movie world was safe . . . .” Movies stop and encapsulate time, allow the observer to rewind, to pause, to fast forward through the sad or scary parts.

Kevin Carey’s world is a heart-wrenching ocean-scape, pulled taut by the shore of the past and island of the present. In Jesus Was a Homeboy, the chanting “we are here/we are here/we are here” became the sound of heavy crying, or of the waves reaching and leaving continuously. After finishing Jesus Was a Homeboy, I could feel the weight of memory, how those voices approach and press up against us inexorably:

The more they eat, the more they come,

The line feeding on itself and growing,

like the Blob in the Steve McQueen movie . . . .

and for a moment I stop what I am doing,

stand with my hands on my hips,

look at the bobbing heads, the hungry mouths,

the dark ocean across the street . . . .

(“Revere Beach After Hours”)

Kevin Carey teaches at Salem State University. He has published two previous books, The One Fifteen to Penn Station (CavanKerry Press, 2012) and The Beach People (Red Bird Chapbooks, 2014). Kevin is also a playwright and a filmmaker. His 2012 co-directed documentary about New Jersey poet Maria Mazziotti Gillan is called All That Lies Between Us.