One Last Supper

We eat around the painted black picnic table,

in the kitchen, kids on benches, Mom in her captain’s chair,

crossing legs, leaning back, drawing on a Pall Mall

(red), picking tobacco flecks from her lower lip, flicking

them toward the clay ashtray somebody made in 2nd or 3rd grade.

She waggles the unclasped buckles on the galoshes she wears

on her left dangling foot, squints against the smoke,

and, straight-faced, jokes: Well, Walt Clyde Frazier can’t hit

a basket to save his life so those Knicks ain’t going nowhere fast.

That makes Pat laugh. You don’t know what you’re talking

about, he says. He starts varsity, power forward,

fails every subject except industrial arts and geometry.

Mom shrugs, scoffs, then spits and coughs, and that

turns Pat sulky (our code for his dark mad moods) so when he rises to leave before dessert Mom stubs her butt, reminds

him he’s old enough to clear his place and now,

decades later, after he’s been dead so long, I only remember

his freckles, the length of his fingernails, the way his brown hair

curtained one eye, but I can’t recall whether he scraped

his plate or just let it slide into an overcrowded sink.

John Francis Istel

We eat around the painted black picnic table,

in the kitchen, kids on benches, Mom in her captain’s chair,

crossing legs, leaning back, drawing on a Pall Mall

(red), picking tobacco flecks from her lower lip, flicking

them toward the clay ashtray somebody made in 2nd or 3rd grade.

She waggles the unclasped buckles on the galoshes she wears

on her left dangling foot, squints against the smoke,

and, straight-faced, jokes: Well, Walt Clyde Frazier can’t hit

a basket to save his life so those Knicks ain’t going nowhere fast.

That makes Pat laugh. You don’t know what you’re talking

about, he says. He starts varsity, power forward,

fails every subject except industrial arts and geometry.

Mom shrugs, scoffs, then spits and coughs, and that

turns Pat sulky (our code for his dark mad moods) so when he rises to leave before dessert Mom stubs her butt, reminds

him he’s old enough to clear his place and now,

decades later, after he’s been dead so long, I only remember

his freckles, the length of his fingernails, the way his brown hair

curtained one eye, but I can’t recall whether he scraped

his plate or just let it slide into an overcrowded sink.

John Francis Istel

John Francis Istel has contributed arts coverage to The Atlantic, Elle, The Village Voice, Mother Jones, and others. His poetry and fiction have appeared in New Letters, Weave, Word Riot, Ginger Piglet, Linden Avenue, and Brooklyn Free Press. He teaches English on NYC's Lower East Side at New Design High School.

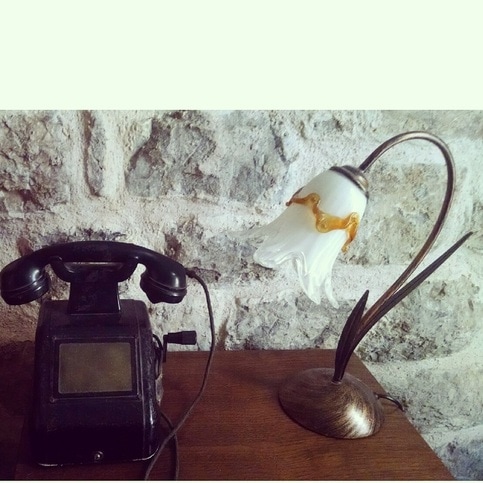

Alyssa Yankwitt is a poet, teacher, bartender, sometimes photographer, and earth walker. She has incurable wanderlust, enjoys drinking whiskey, hates writing about herself in third person, and loves a good disaster.