Interview with June Sylvester Saraceno

Up the Staircase Quarterly: Your latest poetry collection, The Girl From Yesterday (Cherry Grove Collections 2020), begins with a quote from Carolyn Forché: “The people of this world are moving into the next, and with them their hours and the ink of their ability to make thought.” How did you discover this quote, and what attracted you to its concept? How does it relate to the tone or story of The Girl From Yesterday?

June Sylvester Saraceno: The quote is from the poem “Nocturne” in Carolyn Forché’s collection Blue Hour, which I was rereading one summer while working on The Girl From Yesterday. She creates near-mystical experiences based on memory, almost hallucinatory in their effect, and I hoped to learn from her work. Many of the poems in Girl center on the memory of lost ones, how simultaneously absent and present they are, and how the questions we might have asked of them will remain unanswered, a kind of haunting.

UtSQ: It has been a handful of years since the release of your last poetry collection, Of Dirt and Tar (Cherry Grove Collections 2014). Tell us about your process creating and formulating The Girl From Yesterday. Was this a long-term project that spanned several years or did it come together more quickly? What in particular were you hoping to confront or investigate with this project?

JSS: I’m a pretty slow writer. Most of my writing is done in summertime when I’m on break from teaching. I was fortunate enough to have two summer writing residencies in Marnay-sur-Seine, France, and that is where most of the poems in this collection originated. The poems confront loss and displacement, the dissolution of a long marriage, the seemingly endless mourning for loved ones who’ve moved on to that next world, and the desire to gather all my fragments together into some sort of wholeness.

UtSQ: The Girl From Yesterday is divided into three distinct sections that allow the reader to accompany the speaker through different periods of memory. How are these sections connected or disconnected to one another? Why was it important to create these divisions?

JSS: The first section has quite a few elegies. Memories of my family when I was a child swirl together with memories of raising my son. The second section moves away from home settings. There’s a thread of ‘dislocution’ to use Joyce’s term—the difficulty of language, including the tension between trying to speak in one language, and write in another, as well as attempting to articulate something that felt ineffable, almost beyond words. A phrase of Rilke’s that I include in that section seemed to express it well “to neither quite belonging.” The movement in the third section is forward, a sort of reclamation, the ink not yet run dry, enough left to draw a map with a bridge between worlds.

UtSQ: After I read Of Dirt and Tar a few years ago, I was compelled by your use of lightness/darkness, and how the duality of this concept mobilized your writing. After reading The Girl From Yesterday, I noticed elements of this duality again. One example from this book was in the poem “Prodigal Birthright”: “We sorted ourselves, like dark colors and light, to be washed separately.” I’m curious to hear more about this concept in your writing. Does it emerge as a conscious choice or is it more of a natural occurrence? What themes did duality help you highlight in The Girl From Yesterday?

JSS: I’m afraid a fixation on duality might be the result of a fundamentalist Christian upbringing. When you’re raised with a dualistic sense of the world—heaven v. hell, good v. evil, right v. wrong—you may end up spending a lifetime sorting that out. In that poem “Prodigal Birthright” the mother and daughter can’t be separated like clothes, even though the attempt is clear. Even when the daughter runs away, she takes the mother with her, inside her. Even when the mother dies, the die is cast for the daughter, the inheritance at a cellular level. The daughter was always going to return. So was the mother. I think I was engaged in an effort to move beyond dualities into unifying opposites, here and gone, now and then.

UtSQ: I was delighted to find that “Night Currents”, published in Up the Staircase Quarterly, was the ending poem to this collection. Upon re-reading it, I was immediately reminded of how drawn I originally was to the dark freedom represented in the last stanza:

Now when the river eddies into noirish snakes,

we do not fear it. We still do not understand it,

but we care less and less. One day it will empty.

Can you tell us a little more about how you shaped this poem to life? What role does this poem inhabit in your book?

JSS: That’s a perfect description “dark freedom” and thank you so much for choosing to publish that poem! An uncertain freedom may be the only kind possible for us, given that we’ll have our hearts ripped out and served up to us from time to time. But it keeps beating. We learn a different kind of beauty then. The last two poems in the collection are the release, but “Night Currents” is the more enigmatic of the two, so it seemed like the right finishing note, a bit of unknown, an invitation to end and begin again.

UtSQ: I’m curious how your writing journey began. What was your first significant literary encounter? How did this experience inspire you, or shape you, into the writer you have become?

JSS: I wrote in diaries when I was young, as far back as when I pretended to be Nancy Drew in middle school. In my angsty teen years I filled journals, attempted a novel, wrote poetry. I had several heroic high school teachers. My college days were when I really came to see writing as a lifelong direction. My poetry professor at East Carolina University, Peter Makuck, was hugely influential and remains a dear friend and mentor. He still reads drafts of my work and gives me feedback. He deserves a medal.

UtSQ: Finally, June, if you could have a meal with anyone, dead or alive, real or imaginary, whom would it be, what would you talk about, and what on earth would the two of you eat?

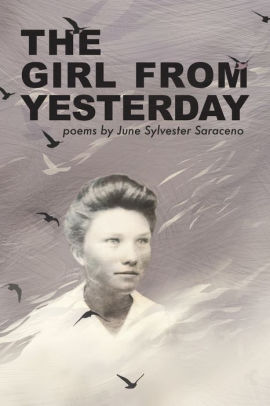

JSS: OK, so this is going to be a little clichéd, given that my options would include folks that I’d definitely like to have this experience with—Shakespeare, Mary Magdalene, Elizabeth I—so many extraordinary people! But it would be my mother. That’s her face on the cover of The Girl From Yesterday. She died when I was in my 20s. I was still so self-absorbed then, I didn’t take care to learn everything I could about her life. In the poem “Salvage” I speculate on some of the questions I would ask her, some of the parts of her life I remain curious about. She’s moved on to that next world and taken her hours and the ink of her thought with her, and I’m still bereft, after all these years. What would we eat? That’s easy! All the things we loved when I was growing up—collard greens just the way she made them, cucumbers in vinegar, sliced tomatoes from our garden, hush puppies, sweet tea, a six layer chocolate cake, strawberries still warm from the sun—to name a few things on that table. And I hope that meal would last forever.

Interview by April Michelle Bratten.

|

June Sylvester Saraceno is the author of Feral, North Carolina, 1965, her debut novel, listed in BuzzFeed as one of “18 Must Read Books from Smaller Presses.” The Girl From Yesterday, her third poetry collection, was released in January 2020. Her previous poetry books are of Dirt and Tar, Altars of Ordinary Light, and a chapbook of prose poems, Mean Girl Trips. She serves as Humanities and English department chair at Sierra Nevada University, Lake Tahoe, where she teaches in the undergraduate and graduate creative writing programs. She is the director of the literary speaker series Writers in the Woods, and founding editor of the Sierra Nevada Review. For more information visit www.junesaraceno.com |