Interview with Kelly Grace Thomas

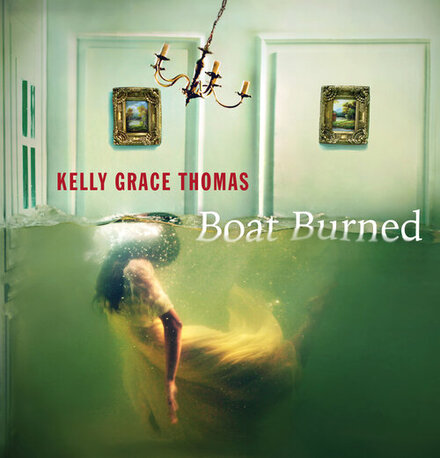

Up the Staircase Quarterly: Boat Burned (YesYes Books, 2020), your first full-length poetry collection, begins with quotes from Sun Tzu and Robin Coste Lewis. The latter wrote: “There is no cure. Sometimes the only remedy is to get back on a boat, to go back to sea. Which is to say, some part of me remains tied to Her mast.” How did you discover this quote from Robin Coste Lewis, and what attracted you to its concept? How does it relate to the tone or story of Boat Burned?

Kelly Grace Thomas: I will never forget the moment when those lines found me. I was in a bathtub in Charlottesville, Virginia, about to attend the Virginia Quarterly Review conference. I was reading the epilogue to Voyage of the Sable Venus for work and I read, “sometimes the only remedy is to get back on the boat, go back to sea.” And I thought, that is what this collection is doing, it is bringing me back to sea. It is asking me to visit the beginning, to examine where this all started. To move with the waves, the world, the emotion to trace my path back, to see how I got here. The stanza before reads:

“There is a disease the French call mal de débarquement; in English, it is called disembarkment sickness; an illness one feels after a prolonged voyage at sea.

After the trip has ended one still feels the ocean rocking beneath one’s feet. The whole room sways as if the house were floating atop an ocean.”

Spending so much time on boats I had felt that rocking all my life, I would be eating dinner after a day on the water and still feel the up and down of it all, the gentle bobbing of the boat singing with the waves. If I close my eyes, I can feel it now. So much of this collection is a metaphor for what boats mean in terms of womanhood, I thought it was the perfect entry into the collection. To say, “I’m still rocking. Here’s why.”

UtSQ: Throughout this work, there are a plethora of references to burning, including: “I hold a match / to everything I no longer am” (“Vesseled”), “I can't turn back. / I strike a single match / burn myself brighter / The boats that built me / smoke on shore” (“Burn the Boats”), and “I was raised arson” (“Dear Kerosene”). Tell us more about this concept in Boat Burned. What role does burning portray in your work? What idea or feeling are you hoping readers take away from this collection?

KGT: As an Aries from New Jersey, I’m driven by fire in every sense of the word. Driven by the sense of electricity and spark. Easily excited or ignited, most would describe me as having a fiery personality and demeanor. Still, I’m so drawn to the water. The soothe and flow of it, but also its power and depths. Maybe it’s the yin and yang. I thought about that dichotomy a lot when writing Boat Burned. The quote that sets up the manuscript by Sun Tzu says, “When your army has crossed the border, you should burn your boats…” Meaning victory is the only choice, there is no going back. This leads me to think a lot about the role of fire as both illumination and transformation. We think of fire as a great destructor, but in a way it also resets. Fire burns something down so something new can build. In nature, it is the clearing of brush. With cooking, it transforms one thing to another, normally to nourishment. Yes, it is destructive, but it also opens a window for creation, space, rebirth that wasn’t there before. It gives the choice to make a new life.

In Boat Burned fire was the act to reclaim and redefine identity and more importantly the power of the speaker. I hoped that readers would take away the idea that sometimes to build a new name you must burn another. I want to collect to inspire, to help others reexamine the ideas, and identities that limit them. More importantly to question why. I want readers to feel inspired to “burn their boats”, to walk away from everything false or unloving they believe about themselves.

During my book launch (which was very short due to COVID) I had audience members write down what boat or boats they needed to burn on a water-soluble slip of paper at the beginning of the reading. At the end of the reading, since I couldn’t light them on fire, we dissolved the paper in a water ceremony. It was emotional and after people raved about it. I’m actually teaching two poetry workshops in September based on this concept.

UtSQ: The contrast of fire and water as a concept could prove to be a unique challenge from a craft standpoint, however within this theme you also managed to discuss gender roles, racism, eating disorders, and identity, among others. I’m curious how Boat Burned’s ideas came together as a whole. What was your process for weaving together these intricate poems into a cohesive arc? Was there a particular challenge you faced while writing these poems and formulating the book?

KGT: I started submitting Boat Burned three years before it was accepted by YesYes Books. It definitely wasn’t done, but you don’t know what you don’t know. However, every time it was rejected I would go back, write more poems, think about the narratives, and through lines of my story that weren’t there. I knew it wasn’t complete, yet.

Most of the things you have mentioned in the question directly affected me or someone I loved, so I felt them very much. I’m a big feeler, as most poets are. They were present in my life, driving me to interrogate and examine truths, ideas, experience. However, I wasn’t sure of how they would all become a cohesive narrative.

It wasn’t until I wrote the “Boat of my Body” that I found the overarching metaphor, women or bodies as boats, that the collection really started driving itself. When I came to this collection I didn’t like the woman I was. I was apologetic and constantly reaching outside myself for power. In these poems, I ask myself why. I thought about how that belief manifested in the behavior of not only myself but the rest of the world.

I knew the story I wanted to tell, while often sad and stormy, this book is a book of love poems, a reclamation of the self. Once I felt like I had enough pockets of all the stories that had taught me shame, but also taught me tenderness I placed all the poems on the ground and started examining the holes, or what I call linchpin poems. I asked myself “what stories have I still not told” and wrote into those spaces. After that, the poems started speaking to themselves, they took over driving. Maybe it's woo woo, but I believe they guided me where they wanted to go.

UtSQ: Two poems from Boat Burned were published in Up the Staircase Quarterly back in early 2019: “Dear Kerosene” and “My Father Tells Me Pelicans Blind Themselves”. Both are stunning, but I’ve always been particularly intrigued by the use of the pelican symbol in “My Father Tells Me…” Do you recall your first moment of inspiration for this poem? Are there any particular lines that stand out the most for you?

KGT: I can recall the sound of my father’s voice, but I don’t know where we were. If I close my eyes I picture us on a pier or somewhere in California on the water. I was sharing my love of pelicans. I spent a month sailing from New Jersey to Florida when I was younger, after my family went bankrupt and my dad relocated. During that sail we saw pelicans almost every day, they moved with such grace and boldness. My mother grew really fond of them and bought a necklace with a pelican pendant. They will forever remind me of her.

During this conversation with my father, I mentioned how beautiful pelicans were. He told me that they go blind searching for food. They dive into the water with their eyes open to find fish, over time the impact ultimately blinds them. The more I did research the more I found this was a myth, but the idea of how pelicans blind themselves to fill a need, and how they peck at their parents really resonated with me. My whole life hunger, whether literal or metaphorical, has stolen parts of my vision. Also, this manuscript is so personal, at times I felt like I was pecking at my family, or more importantly my past. I wanted to write a poem that could carry all that.

UtSQ: Tell us about your first significant literary encounter. How did this experience inspire you, or shape you, into the writer you have become?

KGT: Wow. I have been blessed to have so many. I had no formal training as a poet before the age of 35. I was entirely self-taught. What I learned I learned from reading. I had mentioned to someone that I had always wanted an MFA but am not in the position where I can relocate and low residency programs are out of my price range. Someone mentioned week-long workshops where you can travel and work with various mentors. I have been blessed to work with Patricia Smith, Franny Choi, Danez Smith, Carl Phillips, Shira Ehrlichman… I mean, just such brilliant poets. However, the one that stands out most is Jericho Brown. I studied with him at the VQR Conference mentioned above and I was blown away by his commitment to the work.

He told us in his workshop group that he reads for two hours every day. Yes, to better his work, but also as an obligation to his students. He needs to know the poets that will guide them best even if it is not the ones that guide him best. He said when he finds a poet he is intrigued by he reads all their books, then he looks up their influences and reads all their books, and so on. The man is a walking library and one of the best teachers I have ever had the privilege of learning from, which I don’t say lightly. He has such discipline and love for the craft. He was also writing duplexes at the time, which I thought were just the coolest. He taught me so much about the questions to ask my work, the questions we need to ask all poems, and why they are so important.

UtSQ: Finally, Kelly, if you could have a meal with anyone, dead or alive, real or imaginary, who would it be, and what on earth would the two of you eat?

KGT: This is a great question, and there are so many answers that I don’t know if asked tomorrow the answer would be the same, but today I would have dinner with Allen Ginsberg. I’m so drawn to the wildness in his work, as well as the history of Howl. The poem was literally put on the stand with the Supreme Court and examined under freedom of speech. It defended what art could be. What poetry could be. Published by Lawrence Ferlinghetti from City Lights, this wasn’t Random House or Penguin, there were no corporate contracts or the required number of Instagram followers, in fact, the Beats didn’t care who liked them, it was just a group of friends that believed in one another’s writing who wanted to do their own thing, create and not apologize for it. I also admire Ginsberg’s expression of sexuality and anti-war efforts. I admire how publicly vulnerable he was and how absolutely himself.

I would want us to feast on a traditional east coast, seafood feast with New England clam chowder, steamers, Maine lobster, a crisp Sauvignon Blanc or Chardonnay, and some cookie dough truffles for dessert. My stomach is growling thinking about it.

We would discuss so many things: the changes he saw in the world, what repeated, what transformed, the challenge and secrets to staying “you” even in the face of such hate and opposition. But what I really would want to know is how to maintain an artistic life with creation at the center, now and always. Like everyone who loves to write, I want to be my job, to be at it full time. I’m blessed to work in the field of poetry, but I struggle with all the other demands, especially financial, that take me away from my own work. I would ask him how to always follow my “inner moonlight”, especially during the darkest nights.

Kelly Grace Thomas: I will never forget the moment when those lines found me. I was in a bathtub in Charlottesville, Virginia, about to attend the Virginia Quarterly Review conference. I was reading the epilogue to Voyage of the Sable Venus for work and I read, “sometimes the only remedy is to get back on the boat, go back to sea.” And I thought, that is what this collection is doing, it is bringing me back to sea. It is asking me to visit the beginning, to examine where this all started. To move with the waves, the world, the emotion to trace my path back, to see how I got here. The stanza before reads:

“There is a disease the French call mal de débarquement; in English, it is called disembarkment sickness; an illness one feels after a prolonged voyage at sea.

After the trip has ended one still feels the ocean rocking beneath one’s feet. The whole room sways as if the house were floating atop an ocean.”

Spending so much time on boats I had felt that rocking all my life, I would be eating dinner after a day on the water and still feel the up and down of it all, the gentle bobbing of the boat singing with the waves. If I close my eyes, I can feel it now. So much of this collection is a metaphor for what boats mean in terms of womanhood, I thought it was the perfect entry into the collection. To say, “I’m still rocking. Here’s why.”

UtSQ: Throughout this work, there are a plethora of references to burning, including: “I hold a match / to everything I no longer am” (“Vesseled”), “I can't turn back. / I strike a single match / burn myself brighter / The boats that built me / smoke on shore” (“Burn the Boats”), and “I was raised arson” (“Dear Kerosene”). Tell us more about this concept in Boat Burned. What role does burning portray in your work? What idea or feeling are you hoping readers take away from this collection?

KGT: As an Aries from New Jersey, I’m driven by fire in every sense of the word. Driven by the sense of electricity and spark. Easily excited or ignited, most would describe me as having a fiery personality and demeanor. Still, I’m so drawn to the water. The soothe and flow of it, but also its power and depths. Maybe it’s the yin and yang. I thought about that dichotomy a lot when writing Boat Burned. The quote that sets up the manuscript by Sun Tzu says, “When your army has crossed the border, you should burn your boats…” Meaning victory is the only choice, there is no going back. This leads me to think a lot about the role of fire as both illumination and transformation. We think of fire as a great destructor, but in a way it also resets. Fire burns something down so something new can build. In nature, it is the clearing of brush. With cooking, it transforms one thing to another, normally to nourishment. Yes, it is destructive, but it also opens a window for creation, space, rebirth that wasn’t there before. It gives the choice to make a new life.

In Boat Burned fire was the act to reclaim and redefine identity and more importantly the power of the speaker. I hoped that readers would take away the idea that sometimes to build a new name you must burn another. I want to collect to inspire, to help others reexamine the ideas, and identities that limit them. More importantly to question why. I want readers to feel inspired to “burn their boats”, to walk away from everything false or unloving they believe about themselves.

During my book launch (which was very short due to COVID) I had audience members write down what boat or boats they needed to burn on a water-soluble slip of paper at the beginning of the reading. At the end of the reading, since I couldn’t light them on fire, we dissolved the paper in a water ceremony. It was emotional and after people raved about it. I’m actually teaching two poetry workshops in September based on this concept.

UtSQ: The contrast of fire and water as a concept could prove to be a unique challenge from a craft standpoint, however within this theme you also managed to discuss gender roles, racism, eating disorders, and identity, among others. I’m curious how Boat Burned’s ideas came together as a whole. What was your process for weaving together these intricate poems into a cohesive arc? Was there a particular challenge you faced while writing these poems and formulating the book?

KGT: I started submitting Boat Burned three years before it was accepted by YesYes Books. It definitely wasn’t done, but you don’t know what you don’t know. However, every time it was rejected I would go back, write more poems, think about the narratives, and through lines of my story that weren’t there. I knew it wasn’t complete, yet.

Most of the things you have mentioned in the question directly affected me or someone I loved, so I felt them very much. I’m a big feeler, as most poets are. They were present in my life, driving me to interrogate and examine truths, ideas, experience. However, I wasn’t sure of how they would all become a cohesive narrative.

It wasn’t until I wrote the “Boat of my Body” that I found the overarching metaphor, women or bodies as boats, that the collection really started driving itself. When I came to this collection I didn’t like the woman I was. I was apologetic and constantly reaching outside myself for power. In these poems, I ask myself why. I thought about how that belief manifested in the behavior of not only myself but the rest of the world.

I knew the story I wanted to tell, while often sad and stormy, this book is a book of love poems, a reclamation of the self. Once I felt like I had enough pockets of all the stories that had taught me shame, but also taught me tenderness I placed all the poems on the ground and started examining the holes, or what I call linchpin poems. I asked myself “what stories have I still not told” and wrote into those spaces. After that, the poems started speaking to themselves, they took over driving. Maybe it's woo woo, but I believe they guided me where they wanted to go.

UtSQ: Two poems from Boat Burned were published in Up the Staircase Quarterly back in early 2019: “Dear Kerosene” and “My Father Tells Me Pelicans Blind Themselves”. Both are stunning, but I’ve always been particularly intrigued by the use of the pelican symbol in “My Father Tells Me…” Do you recall your first moment of inspiration for this poem? Are there any particular lines that stand out the most for you?

KGT: I can recall the sound of my father’s voice, but I don’t know where we were. If I close my eyes I picture us on a pier or somewhere in California on the water. I was sharing my love of pelicans. I spent a month sailing from New Jersey to Florida when I was younger, after my family went bankrupt and my dad relocated. During that sail we saw pelicans almost every day, they moved with such grace and boldness. My mother grew really fond of them and bought a necklace with a pelican pendant. They will forever remind me of her.

During this conversation with my father, I mentioned how beautiful pelicans were. He told me that they go blind searching for food. They dive into the water with their eyes open to find fish, over time the impact ultimately blinds them. The more I did research the more I found this was a myth, but the idea of how pelicans blind themselves to fill a need, and how they peck at their parents really resonated with me. My whole life hunger, whether literal or metaphorical, has stolen parts of my vision. Also, this manuscript is so personal, at times I felt like I was pecking at my family, or more importantly my past. I wanted to write a poem that could carry all that.

UtSQ: Tell us about your first significant literary encounter. How did this experience inspire you, or shape you, into the writer you have become?

KGT: Wow. I have been blessed to have so many. I had no formal training as a poet before the age of 35. I was entirely self-taught. What I learned I learned from reading. I had mentioned to someone that I had always wanted an MFA but am not in the position where I can relocate and low residency programs are out of my price range. Someone mentioned week-long workshops where you can travel and work with various mentors. I have been blessed to work with Patricia Smith, Franny Choi, Danez Smith, Carl Phillips, Shira Ehrlichman… I mean, just such brilliant poets. However, the one that stands out most is Jericho Brown. I studied with him at the VQR Conference mentioned above and I was blown away by his commitment to the work.

He told us in his workshop group that he reads for two hours every day. Yes, to better his work, but also as an obligation to his students. He needs to know the poets that will guide them best even if it is not the ones that guide him best. He said when he finds a poet he is intrigued by he reads all their books, then he looks up their influences and reads all their books, and so on. The man is a walking library and one of the best teachers I have ever had the privilege of learning from, which I don’t say lightly. He has such discipline and love for the craft. He was also writing duplexes at the time, which I thought were just the coolest. He taught me so much about the questions to ask my work, the questions we need to ask all poems, and why they are so important.

UtSQ: Finally, Kelly, if you could have a meal with anyone, dead or alive, real or imaginary, who would it be, and what on earth would the two of you eat?

KGT: This is a great question, and there are so many answers that I don’t know if asked tomorrow the answer would be the same, but today I would have dinner with Allen Ginsberg. I’m so drawn to the wildness in his work, as well as the history of Howl. The poem was literally put on the stand with the Supreme Court and examined under freedom of speech. It defended what art could be. What poetry could be. Published by Lawrence Ferlinghetti from City Lights, this wasn’t Random House or Penguin, there were no corporate contracts or the required number of Instagram followers, in fact, the Beats didn’t care who liked them, it was just a group of friends that believed in one another’s writing who wanted to do their own thing, create and not apologize for it. I also admire Ginsberg’s expression of sexuality and anti-war efforts. I admire how publicly vulnerable he was and how absolutely himself.

I would want us to feast on a traditional east coast, seafood feast with New England clam chowder, steamers, Maine lobster, a crisp Sauvignon Blanc or Chardonnay, and some cookie dough truffles for dessert. My stomach is growling thinking about it.

We would discuss so many things: the changes he saw in the world, what repeated, what transformed, the challenge and secrets to staying “you” even in the face of such hate and opposition. But what I really would want to know is how to maintain an artistic life with creation at the center, now and always. Like everyone who loves to write, I want to be my job, to be at it full time. I’m blessed to work in the field of poetry, but I struggle with all the other demands, especially financial, that take me away from my own work. I would ask him how to always follow my “inner moonlight”, especially during the darkest nights.

|

KELLY GRACE THOMAS is the winner of the 2017 Neil Postman Award for Metaphor from Rattle, 2018 finalist for the Rita Dove Poetry Award and multiple pushcart prize nominee. Her first full-length collection, Boat Burned, released with YesYes Books in January 2020. Kelly’s poems have appeared or are forthcoming in: Best New Poets 2019, Los Angeles Review, Redivider, Nashville Review, Muzzle, DIAGRAM, and more. Kelly currently works to bring poetry to underserved youth as the Director of Education and Pedagogy for Get Lit-Words Ignite. Kelly is a three-time poetry slam championship coach and the co-author of Words Ignite: Explore, Write and Perform, Classic and Spoken Word Poetry (Literary Riot), currently taught in the Los Angeles Unified School District. Kelly has received fellowships from Tin House Winter Workshop, Martha's Vineyard Institute of Creative Writing and the Kenyon Review Young Writers. Kelly and her sister, Kat Thomas, won Best Feature Length Screenplay at the Portland Comedy Film Festival for their romantic comedy, Magic Little Pills. Kelly lives in the Bay Area with her husband, Omid, and is currently working on her debut novel, a YA thriller, titled Only 10.001. www.kellygracethomas.com |