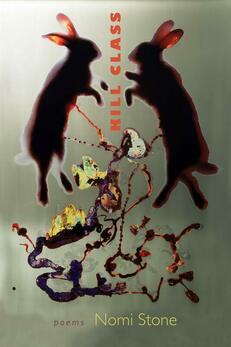

Kill Class by Nomi Stone

Paperback: 108 pages

Publisher: Tupelo Press, February 1, 2019

Purchase @ Tupelo Press

Review by Jennifer Martelli.

In her poem, “Mosque / School Room,” Nomi Stone writes,

I am learning how to be an anthropologist. Anthropologists are

furious and want

culture back. Every day in this wood, I drink tea, fragrant and

black / and wait very slowly

for them to open, and for me to open; it is a green ache and it is

nothing if not need.

Using the voice of “the anthropologist,” Nomi Stone’s Kill Class recounts two years “of ethnographic fieldwork, observing pre-deployment exercises in mock Middle Eastern villages at four military bases across the United States.” The structured unreality—a stage in which all the horrors of war are play-acted—is as un-relenting as hunger. In this fictional country of “Pineland,” the anthropologist lives among people of Middle Eastern backgrounds playing Middle Easterners, all “actors” re-enacting war, mourning, and death. The poems depict, in their structures, the unreality of Pineland, which is seen and heard in the poet’s choices of diction, punctuation, and attention to the body.

As I was reading Kill Class, I thought of a sculpture I’d first encountered in Claudia Rankine’s Citizen. Kate Clark’s “Little Girl,” is a shocking collaboration; Clark used remnants from taxidermists—in this case, an infant caribou—and attached the face of a young black girl. One can see the taxidermist’s tacks around the face, and the eyes, staring, as is from a mask. Are these the girl’s eyes? or the caribou’s? Are they looking at me? Who is beneath the skin? The pelt? Kill Class confronts the reader in this same way. By blurring the boundaries of reality and humanity, we ask, “Where does the role-playing begin?” Stone, in her poem “The Hunter Dresses His Prey,” is constantly bringing the reader back to this question:

. . . . Face

to face, both not & yes;

both dead & loved, am I

your calf / I am your calf.

The town in the fictional Pineland wears a costume as well. Stone describes the building/birth of the town in “Quadrant,” as “The village rises into form between the pines. / Cows and goats stand in the forest. Flimsy wood . . . . ” The description resembles a movie set:

POLICE STATION/ CRYING ROOM

JAIL

BROKEN-IN

INTERNET CAFÉ MOSQUE/SCHOOL

Even the land is unsteady, a shifting scape, an ill-fitting costume:

Over the mock grave

they open the real earth

and plant fresh pinecones.

(“War Game: America”)

Stone ends many of her poems in Kill Class with a softness. Either by sound or imagery, Stone returns to a gentle place, or perhaps a grieving place. The reader is given respite with ending words, like “fade,” “heart,” “dark,” “sleep,” “room,” “wind.” In “Plug in the Role and Play,” the anthropologist states

You asked the part

of me I kept hidden. It was every

softness I didn’t give them,

the life awake,

whole,

trembling.

The anthropologist’s heart maintains the reader. In a book filled with poems that shake reality to the core, the speaker instructs us in “Love Poem” to

Undo the next time beauty

turns into tenderness turns

into a killing . . . .

Just as tenderness is written into the poems, so is uncertainty. I loved Stone’s use of brackets and slashes: they cut up the poems, but also, enact a choice left to the anthropologist or to the reader: we are witnessing something staged. Isn’t this strange to watch, the anthropologist [I] asks / the Iraqis . . . . (“The Notionally Dead”). The anthropologist is constantly reminded—or reminds us—that this world of Pineland is all staging:

The war scene has: [vegetable stalls], [roaming animals],

and [people] in it . . . .

Some

of the people over there are good /

others evil / others circumstantially

bad / some only want

cash / some just want

their family not to die.

The game says figure

out which

are which.

(“War Game: Plug and Play”)

Throughout Kill Class, Stone references hunger—the body’s most basic need beyond survival. In “A Black Sun,” Stone writes, “Jinn eat through the weak, blacken the sun; / one part of you goes, the other part, no: a halt, a freeze . . . .” The poems—like the little girl’s eyes—return to this need again and again. The vulnerability of the speaker in “The Anthropologist” addresses her own complicity in—and the cost of—being a witness to this “game”:

It’s true, they take me for

BBQ after, ask me if I am comfortable, do I want dessert and what

do I think I know about them and do I know any Americans who

went to war or don’t I and if I don’t who do I think I am, and do I

agree that through my

stomach, they will get

my heart?

Just like the figure of the little caribou girl, the poems in Kill Class examine the nature of looking, the nature of wanting. “Anthropologist, why are you in this story,” the speaker asks in “The Camera Burned a Hole.” Stone confronts the cost of creating a realistic un-reality. The blurring of place, or character, and of language is recounted in her poems that always return to the heart:

Take this road into the body / return it

as a love

letter. Body

a simmering lake

of code, nutrient,

wishing. In Arabic,

there is a word that means the cleaving

from dormancy or sorrow

into first joy.

(“The Door”)

Nomi Stone’s Kill Class identifies love as the most primal hunger, forces us to confront our own humanity, just as the anthropologist does in this play, while being anchored to the truest part of the self, “(he explains, have I translated this correctly?),” Stone writes in her final poem of the collection, “you will have a very strong heart.”

Nomi Stone’s second collection of poems, Kill Class is forthcoming from Tupelo Press in 2019. Poems appear recently or will soon in The New Republic, The New England Review, Tin House, Bettering American Poetry 2017, The Best American Poetry 2016, Guernica, and widely elsewhere. Kill Class is based on two years of fieldwork she conducted within war trainings in mock Middle Eastern villages erected by the US military across America.

Nomi Stone’s second collection of poems, Kill Class is forthcoming from Tupelo Press in 2019. Poems appear recently or will soon in The New Republic, The New England Review, Tin House, Bettering American Poetry 2017, The Best American Poetry 2016, Guernica, and widely elsewhere. Kill Class is based on two years of fieldwork she conducted within war trainings in mock Middle Eastern villages erected by the US military across America.