Le Photographe by Didier Lefèvre, Emmanuel Guibert, and Frédéric Lemercier

Le Photographe by Didier Lefèvre, Emmanuel Guibert, and Frédéric Lemercier

Publisher: DUPUIS (2003)

Available at Amazon

Publisher: DUPUIS (2003)

Available at Amazon

Le Photographe: A Timeless Piece of Cultural Commentary

by Maya T. Garabedian.

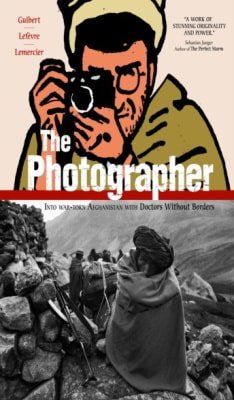

Cultural commentary doesn’t always age well. Tyra Banks forcing America’s Next Top Model contestants to do a “bi-racial” photoshoot on national free-to-air TV. Jimmy Fallon in blackface on Saturday Night Live. Any late night talk show where David Letterman interviews a woman. Kayleigh McEnany’s choice words on Trump five years before becoming White House press secretary. The illustrations in Tintin au Congo. Lolita. If diminishing political correctness is the rule, The Photographer

is an exception. The Photographer: Into War-torn Afghanistan with Doctors Without Borders, the graphic novel by photojournalist Didier Lefèvre, cartoonist Emmanuel Guibert, and colorist Frédéric Lemercier, has stood the test of time.

Originally written in French as Le Photographe in 2003, the book was then translated into English, the version I read, in 2009. The story follows Didier’s trip through Pakistan and into Afghanistan as the photographer for Médecins Sans Frontières during the Soviet-Afghan war of 1986. His tumultuous journey plays out through dialogue, but internal and external, and weaved together with subtle hilarity, Tintin-esque illustrations, and breathtaking, original photographs. Considering the name of the piece, and the fact he took 4,000 photos during his three-month trip, there was a serious lack of photographs, which left the illustrations to do the

heavy lifting of Didier’s tale. Admittedly, with a title like The Photographer, and not The Cartoonist, I felt a little disappointed, or at the very least misled. That being said, the decision to use photographs sparingly did limit distractions from the written story, allowing it to be the focus of the work instead.

With Didier’s writing in the spotlight, his natural ability as a storyteller was able to shine. As someone with a dry sense of humor, I’ve always had a soft spot for French commentary. Contrary to popular belief, I’d argue that it’s much more likely to find dark humor and hopelessness than stereotypical elitistism and hopeless romance—a certain energy that sets French travel narratives in a league of their own. In this sense, Didier is a quintessential French narrator and an ideal travel partner, at least in the realm of literature. As readers, we get to experience the journey alongside Didier, an unprepared, over-confident, risk-taker, without having to be any of those things ourselves, or having the real-world responsibility of being with someone who is. We get to laugh at his deadpan comments to caravan leaders and physicians, like asking if he can dope like the East German female swimmers so he can keep up during the trek. And when he’s hit with an uncomfortable and unrelated response like, “I should have a piece of Afghan cheese” (39), we don’t have to feel any second-hand awkwardness.

More importantly, all the reckless moves he makes along the way, the champion of which was his decision to leave early and attempt the return journey alone, aren’t so sad when he’s such a hot mess. The situations he finds himself in are a direct result of the uninformed moves he made along the way. All we can do, as very far removed stowaways, is chuckle and think to ourselves, Oh, Didier, as if he’s an old friend who’s up to his classic hijinks, and that against all odds, he’ll make it home to tell the tale.

Despite all of these positives, there was one major element that gave me pause, although I’m grateful it didn’t reveal itself until the very end. Using the epilogue, I was able to piece together a timeline surrounding the novel. If this trip took place in 1986, and Didier traveled to Afghanistan more than a dozen times after that, and waited some 20 years before creating this work, it seems unlikely that he’d be able to accurately recall every detail and conversation of that first trip, even with the help of his trusty journal. But he didn’t even have that. In an anecdote almost too lighthearted for the gravity of the situation and its implications, Guibert pokes fun at

the fact Didier’s relationship didn’t last, much like his journal. He had given it to his girlfriend at the time, who then seemed to have lost it during a move, leaving him with only two artifacts from that first trip: his photographs and a different, smaller notebook where he kept his financial records. Coming to this realization was a bit of a sad note to end on for me. However, the ability to be moved by such a revelation speaks to the power of the novel. I enjoyed it so much that I wanted the story I read to remain intact so badly—only a truly special work would cause such an attachment, and The Photographer certainly is one.

by Maya T. Garabedian.

Cultural commentary doesn’t always age well. Tyra Banks forcing America’s Next Top Model contestants to do a “bi-racial” photoshoot on national free-to-air TV. Jimmy Fallon in blackface on Saturday Night Live. Any late night talk show where David Letterman interviews a woman. Kayleigh McEnany’s choice words on Trump five years before becoming White House press secretary. The illustrations in Tintin au Congo. Lolita. If diminishing political correctness is the rule, The Photographer

is an exception. The Photographer: Into War-torn Afghanistan with Doctors Without Borders, the graphic novel by photojournalist Didier Lefèvre, cartoonist Emmanuel Guibert, and colorist Frédéric Lemercier, has stood the test of time.

Originally written in French as Le Photographe in 2003, the book was then translated into English, the version I read, in 2009. The story follows Didier’s trip through Pakistan and into Afghanistan as the photographer for Médecins Sans Frontières during the Soviet-Afghan war of 1986. His tumultuous journey plays out through dialogue, but internal and external, and weaved together with subtle hilarity, Tintin-esque illustrations, and breathtaking, original photographs. Considering the name of the piece, and the fact he took 4,000 photos during his three-month trip, there was a serious lack of photographs, which left the illustrations to do the

heavy lifting of Didier’s tale. Admittedly, with a title like The Photographer, and not The Cartoonist, I felt a little disappointed, or at the very least misled. That being said, the decision to use photographs sparingly did limit distractions from the written story, allowing it to be the focus of the work instead.

With Didier’s writing in the spotlight, his natural ability as a storyteller was able to shine. As someone with a dry sense of humor, I’ve always had a soft spot for French commentary. Contrary to popular belief, I’d argue that it’s much more likely to find dark humor and hopelessness than stereotypical elitistism and hopeless romance—a certain energy that sets French travel narratives in a league of their own. In this sense, Didier is a quintessential French narrator and an ideal travel partner, at least in the realm of literature. As readers, we get to experience the journey alongside Didier, an unprepared, over-confident, risk-taker, without having to be any of those things ourselves, or having the real-world responsibility of being with someone who is. We get to laugh at his deadpan comments to caravan leaders and physicians, like asking if he can dope like the East German female swimmers so he can keep up during the trek. And when he’s hit with an uncomfortable and unrelated response like, “I should have a piece of Afghan cheese” (39), we don’t have to feel any second-hand awkwardness.

More importantly, all the reckless moves he makes along the way, the champion of which was his decision to leave early and attempt the return journey alone, aren’t so sad when he’s such a hot mess. The situations he finds himself in are a direct result of the uninformed moves he made along the way. All we can do, as very far removed stowaways, is chuckle and think to ourselves, Oh, Didier, as if he’s an old friend who’s up to his classic hijinks, and that against all odds, he’ll make it home to tell the tale.

Despite all of these positives, there was one major element that gave me pause, although I’m grateful it didn’t reveal itself until the very end. Using the epilogue, I was able to piece together a timeline surrounding the novel. If this trip took place in 1986, and Didier traveled to Afghanistan more than a dozen times after that, and waited some 20 years before creating this work, it seems unlikely that he’d be able to accurately recall every detail and conversation of that first trip, even with the help of his trusty journal. But he didn’t even have that. In an anecdote almost too lighthearted for the gravity of the situation and its implications, Guibert pokes fun at

the fact Didier’s relationship didn’t last, much like his journal. He had given it to his girlfriend at the time, who then seemed to have lost it during a move, leaving him with only two artifacts from that first trip: his photographs and a different, smaller notebook where he kept his financial records. Coming to this realization was a bit of a sad note to end on for me. However, the ability to be moved by such a revelation speaks to the power of the novel. I enjoyed it so much that I wanted the story I read to remain intact so badly—only a truly special work would cause such an attachment, and The Photographer certainly is one.

Maya T. Garabedian is an Armenian-Lebanese-Sicilian dancer-turned-writer from Boise, Idaho. During her time at UC Santa Barbara, where she graduated in 2019 with a BA in Interdisciplinary Studies, she worked at The Catalyst and Spectrum literary magazines. She was the recipient of the Keith Vineyard Award for Creative Writing, the Chancellor's Award for Excellence in Undergraduate Research, UCSB's CCS Most Excellent Narrative Prose Award, and the Richardson Poetry Award. She currently writes for MutualArt and Popsugar and is pursuing her MFA in Creative Writing from Chapman University, where she received full tuition and non-tuition fellowships.