Interview with Lee Ann Roripaugh

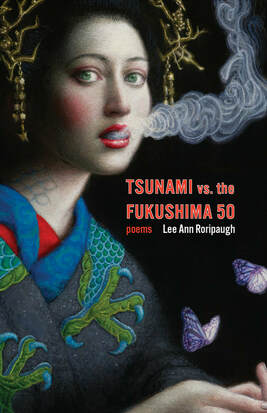

Up the Staircase Quarterly is honored to follow up on our 2015 interview with Lee Ann Roripaugh on her collection tsunami vs the fukushima 50, published this year by Milkweed Editions:

I wish to commemorate Fukushima, and focus public/cultural/artistic attention on Fukushima's ongoing legacies, particularly with respect to environmental crises… In addition to providing a vehicle by which to consider the ecocritical and cultural implications of the Fukushima disaster, this project has blossomed into a canvas that works with aspects of personal and cultural psychological trauma, gender performance and queer identities, the taboo of female rage, and ideas of the monstrous/grotesque. -Lee Ann Roripaugh.

Up the Staircase Quarterly: Lee Ann, thank you for taking the time to talk with us again. I was thrilled to finally read tsunami vs the fukushima 50, which did not disappoint. Can you talk to us a bit about this book’s journey, from original idea to final edit?

Lee Ann Roripaugh: I remember feeling both devastated and haunted by the tsunami and Fukushima disaster, long after it largely disappeared from the mainstream news cycles. The destruction of the tsunami was, of course, horrific, but it also seemed almost too awful to bear that Japan, the country that had been subject to atomic holocaust at the end of WWII, was now the site of a nuclear disaster as well. I was also heartbroken thinking about the larger, long-term environmental impact of the disaster. I began thinking a lot about the Godzilla narratives—and the rise of mutant monsters on Monster Island—and how they emerged as an ecocritical response to the dropping of the atomic bombs at the end of WWII. At the same time, I had recently become immersed in comics, and so I was also fascinated by how many superheroes and/or mutants were created by accidents involving radioactivity. All of these elements, for me, were mixing and swirling around in a heady creative cocktail, and I knew that I wanted to try and see if I could bring these threads together somehow into a book project.

In Summer 2012, I had a one-month residency at Banff, where I hoped to find an entry point into drafting poems for the project. I decided that I would try to create a character called Tsunami a supervillainess, who would face off with the Fukushima 50. And so I plunged in, and ultimately left that summer with a substantial handful of draft poems exploring the character of Tsunami. I continued to write and revise this portion of the book until Spring 2015, when I had a sabbatical. I knew that at this point, I needed to figure out how to construct the other half of the book—the Fukushima 50—who would face off with the feral, catastrophic force that was Tsunami. Because the Fukushima 50 was, in many cases, already a fictional construction (there were more than 50 workers who stayed behind at the plant, for example), I decided to broaden my scope of Fukushima 50 to include everyone who pushed back, resisted, survived, or in some cases succumbed to, Tsunami, and that I would situate them as various comic book superheroes created through accidents with radioactivity. Once I decided that these poems would be set as first-person monologues, assembling my research into characters and voices progressed smoothly. After residencies at Willapa Bay AiR and the Bunnell Street Arts Center, I was able to complete all of the monologues, draft some robot poems for the book, and order the manuscript. The following year, I continued to revise the poems, and added in “song of the mutant super boars” and “ghosts of the tohoku coast,” after which the book was complete, with the exception of final edits.

UtSQ: Because this collection was based on the 2011 tsunami and the nuclear catastrophe at the Fukushima Daiichi power plant, I wanted to make sure the disaster was at the forefront of my mind before I began the book. I went back and read articles on the earthquake, tsunami, and the Fukushima Daiichi and came across a day-to-day timeline of events that I found particularly informative on the Fukushima 50www.livescience.com/13294-timeline-events-japan-fukushima-nuclear-reactors.html, the volunteers who risked their lives to stabilize the reactors. How did you prepare/research for this book?

LAR: Because this was a project that, to me, falls under the rubric of docupoetics, it was definitely research-inensive. I read everything I could get my hands on with respect to the tsunami and nuclear catastrophe. In particular, I set e-mail alerts to receive any and all news, articles, and essays regarding Fukushima, and I read every single one of them, and still do, actually, to this day. I also reacquainted myself with readings in trauma theory, and also read many, many comic books!

UtSQ:

because I am by nature

a quiet and scientific man,

a botanist by trade, but

I work so ferociously at

clearing debris and digging

along the shoreline in search

of my daughter’s remains--

tearing off my hazmat gear

when it gets in the way,

or when it becomes too hot--

that volunteer search teams

have nicknamed me The Hulk

--from “hulk smash”

The shift from third to first person throughout the collection was compelling. How did you navigate assuming the position of citizens effected by the disaster? Were these poems developed from real personal accounts, and if so, what decisions did you make in translating them across language and medium?

LAR: With the exception of two of the characters (“radiation man” and “miki endo as flint marko”), the first-person monologues in the voices of Japanese citizens effected by the disaster were fictional, although the details around which I built (and collaged) their narratives were all factual. For the fictional voices, I would see which facts and details (some of which were culled from personal and/or collective accounts, most of which were culled from news stories and articles) gravitated toward a particular character or voice, and would then collage them into a narrative. In the case of “miki endo as flint marko,” I wished to honor one of the heroes of the tsunami, a young woman who worked at the Disaster Prevention Office in Minamisoma and held her ground on the loudspeaker—repeatedly telling citizens to seek higher ground and run away, until she was eventually swept away by the tsunami. Numerous people in Minamisoma credited her with saving their lives. Her monologue is told from beyond the grave, however, and in that sense, is largely fictional aside from the circumstances of her heroism during the tsunami, of course. In the case of “radiation man,” I conflated stories of two men who stayed behind in the nuclear exclusion zone (the “No Go Zone”) to care for pets and farm animals who had been left behind.

While on the one hand, I wanted to embody and give face to what I feel can be problematic erasures of identity into commodifiable and clichéd spectacles of victimhood and survivorhood—a flattening of self and subject into other and objecthood—at the same time, I also feel that trauma is a time of great vulnerability that also should be accorded privacy. This is what, in part, motivated me, I think, to make these highly-stylized monologues through using the semi-transparent masks of superheroes as conduits for the personas in the poems.

UtSQ:

she’s a mega-tsunami of pure hubris

cross-dressed in high femme

splashy / shiny / crystalline

all liquid curve and fluid light

with her Hello Kitty barrettes

pink glitter ribbons furbelowing

all that snaky girlzilla hair

bored now, she pouts in her little girl voice

before it all goes to shit

—from “beautiful tsunami”

I was struck by how you personified the tsunami, so that “she” became a fully-realized antagonist. Can you describe your process for giving voice to the tsunami?

LAR: I knew from the outset that I wanted Tsunami to be fluid, shapeshift-y, prismatic, and multifaceted. I also knew that I wanted her (and because she is made of water, I always envisioned her as originally presenting as femme, but ultimately being somewhat genderfluid and/or non-binary) to be a complex annihilatrix, like Magneto from the X-Men, whose actions are frequently destructive, even while his intentions are noble. Also, like Magneto, whose superpowers manifested during the trauma of the Holocaust, I wanted Tsunami to be forged through trauma—although, in her case, the trauma is literally the fault-line in the ocean floor causing the earthquake that gives rise to a tsunami. Of course, the challenge was how does one give voice to a powerful and destructive force of nature? And I think the answer, for me, was that Tsunami couldn’t be encapsulated through a single, first-person voice. That would be too reductive. Through using third-person omniscient, however, Tsunami could become a multifaceted series of shifting projections—a polyvocal mirroring of human desires and fears.

UtSQ: I can only imagine that delving so intensely into the circumstances of this tragedy and its ongoing aftermath was challenging on a spiritual level. From a craft standpoint, I’m curious how this affected your ability to give voice to the trauma. Was there a piece that posed a specific challenge? Was there a poem that arrived “easiest” on the page?

LAR: This is such a great question. As you know, my previous book, Dandarians, was intensely confessional, and intensely, sometimes painfully, personal. Moving from the microcosm of private or personal trauma into the macrocosm of public and national trauma was interesting. There are some commonalities, of course, but also obviously some dangers, as well—particularly, I think, in terms of wanting to be very respectful in terms of how I handled traumatic experiences that ultimately belonged to people other than myself. I think this is why I began by writing the third-person Tsunami poems. As an entity, she was in many respects a creative blank slate, and when I envisioned her as being created by trauma, I found that the trauma I imagined her being informed by was most frequently sexual, physical, and emotional violence or abuse. Some of these projections or experiences were my own, of course, but in a greater sense, these also felt like larger cultural projections emanating from female and non-binary subjects. It felt as if there was a rising tide of justifiable anger in the air at the time I began writing the Tsunami poems, and there was something very cathartic/cleansing in being able to give voice to an all-powerful entity in solidarity with a building chorus of female and non-binary voices tripping over the faultline of cultural misogyny and empire.

The most difficult poems for me to write, I think, were the monologues “hisako’s testimony” and “hulk smash”—perhaps because they encapsulated some of the narratives of the most vulnerable of the Fukushima victims/survivors. Although I had conceived of these voices/characters early on during the stage of drafting the Fukushima 50 monologues, I resisted writing these two until the very end, and afterwards, I felt emotionally wrecked. I’ve read “hulk smash” a number of times at readings, and it’s an intense experience, but I’ve read “hisako’s testimony” only once so far because it’s such a painfully difficult narrative for me.

UtSQ:

/ 200

pounds apiece of radioactive boars

bulldozing down the farmland

with glow-in-the-dark hooves

and contaminated snouts / mutant

super boars / new syndicate

of the no go zone / smarter

than charlotte / demagogues

of their own brutal animal farm

—from “song of the mutant super boars”

Your writing often revels in the grotesque, so I was not surprised to discover that this book explores nature’s incongruence with technology and nature’s attempt to survive what humankind has destroyed, dabbling with an idea similar to what Joyelle McSweeney has dubbed the Necropastoral. How do you see your use of the super hero trope fitting into this thought process? What do you hope your work evokes by employing these references?

LAR: Yes, this book is definitely circling around ideas of the Necropastoral and the grotesqueries that result when technology either collides with, or attempts to control, nature. I think that superheroes, particularly in incarnations that are the result of radioactive accidents, are frequently grotesques—beginning with the giant mutant monsters such as Godzilla, Mothra, and Hedora, et al., who rise on Monster Island. But even stretchy, rubbery-limbed Reed Richards of the Fantastic Four, or the Amazing Hulk, or Spider Man (who’s bit by a radioactive spider) are all also grotesque in their own way. And of course, Tsunami herself seems like a harbinger, or hastener, even, for the Anthropocene—not only in terms of her terrible swathe of destruction, but in the ways that she topples the poisonous and contaminating edifices of humankind.

UtSQ: Although your ultimate goal (and achievement) was to commemorate those effected by the tsunami and the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, what did you personally take away from the experience of writing and then publishing these poems?

LAR: At the time that I first began writing and publishing these poems it was still the pre-Trump era, pre-#MeToo, pre-#NoDAPL, and #BlackLivesMatter was a nascent movement following Trayvon Martin’s murder in 2012. What I was feeling at the time was a kind of seismic unease, I think, that became increasingly embodied in the rising tide of social justice movements that have formed since 2011. I feel as if, in addition to commemorating and honoring the tsunami and Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, the book has also become a way to articulate some of the environmental terrors of the Anthropocene. I also like to think of Tsunami—as an all-powerful femme/non-binary entity—as being symbolic of a force that (literally) dismantles, deconstructs, and decolonizes the Westernized edifices of patriarchy and empire. And I love that about her.

I wish to commemorate Fukushima, and focus public/cultural/artistic attention on Fukushima's ongoing legacies, particularly with respect to environmental crises… In addition to providing a vehicle by which to consider the ecocritical and cultural implications of the Fukushima disaster, this project has blossomed into a canvas that works with aspects of personal and cultural psychological trauma, gender performance and queer identities, the taboo of female rage, and ideas of the monstrous/grotesque. -Lee Ann Roripaugh.

Up the Staircase Quarterly: Lee Ann, thank you for taking the time to talk with us again. I was thrilled to finally read tsunami vs the fukushima 50, which did not disappoint. Can you talk to us a bit about this book’s journey, from original idea to final edit?

Lee Ann Roripaugh: I remember feeling both devastated and haunted by the tsunami and Fukushima disaster, long after it largely disappeared from the mainstream news cycles. The destruction of the tsunami was, of course, horrific, but it also seemed almost too awful to bear that Japan, the country that had been subject to atomic holocaust at the end of WWII, was now the site of a nuclear disaster as well. I was also heartbroken thinking about the larger, long-term environmental impact of the disaster. I began thinking a lot about the Godzilla narratives—and the rise of mutant monsters on Monster Island—and how they emerged as an ecocritical response to the dropping of the atomic bombs at the end of WWII. At the same time, I had recently become immersed in comics, and so I was also fascinated by how many superheroes and/or mutants were created by accidents involving radioactivity. All of these elements, for me, were mixing and swirling around in a heady creative cocktail, and I knew that I wanted to try and see if I could bring these threads together somehow into a book project.

In Summer 2012, I had a one-month residency at Banff, where I hoped to find an entry point into drafting poems for the project. I decided that I would try to create a character called Tsunami a supervillainess, who would face off with the Fukushima 50. And so I plunged in, and ultimately left that summer with a substantial handful of draft poems exploring the character of Tsunami. I continued to write and revise this portion of the book until Spring 2015, when I had a sabbatical. I knew that at this point, I needed to figure out how to construct the other half of the book—the Fukushima 50—who would face off with the feral, catastrophic force that was Tsunami. Because the Fukushima 50 was, in many cases, already a fictional construction (there were more than 50 workers who stayed behind at the plant, for example), I decided to broaden my scope of Fukushima 50 to include everyone who pushed back, resisted, survived, or in some cases succumbed to, Tsunami, and that I would situate them as various comic book superheroes created through accidents with radioactivity. Once I decided that these poems would be set as first-person monologues, assembling my research into characters and voices progressed smoothly. After residencies at Willapa Bay AiR and the Bunnell Street Arts Center, I was able to complete all of the monologues, draft some robot poems for the book, and order the manuscript. The following year, I continued to revise the poems, and added in “song of the mutant super boars” and “ghosts of the tohoku coast,” after which the book was complete, with the exception of final edits.

UtSQ: Because this collection was based on the 2011 tsunami and the nuclear catastrophe at the Fukushima Daiichi power plant, I wanted to make sure the disaster was at the forefront of my mind before I began the book. I went back and read articles on the earthquake, tsunami, and the Fukushima Daiichi and came across a day-to-day timeline of events that I found particularly informative on the Fukushima 50www.livescience.com/13294-timeline-events-japan-fukushima-nuclear-reactors.html, the volunteers who risked their lives to stabilize the reactors. How did you prepare/research for this book?

LAR: Because this was a project that, to me, falls under the rubric of docupoetics, it was definitely research-inensive. I read everything I could get my hands on with respect to the tsunami and nuclear catastrophe. In particular, I set e-mail alerts to receive any and all news, articles, and essays regarding Fukushima, and I read every single one of them, and still do, actually, to this day. I also reacquainted myself with readings in trauma theory, and also read many, many comic books!

UtSQ:

because I am by nature

a quiet and scientific man,

a botanist by trade, but

I work so ferociously at

clearing debris and digging

along the shoreline in search

of my daughter’s remains--

tearing off my hazmat gear

when it gets in the way,

or when it becomes too hot--

that volunteer search teams

have nicknamed me The Hulk

--from “hulk smash”

The shift from third to first person throughout the collection was compelling. How did you navigate assuming the position of citizens effected by the disaster? Were these poems developed from real personal accounts, and if so, what decisions did you make in translating them across language and medium?

LAR: With the exception of two of the characters (“radiation man” and “miki endo as flint marko”), the first-person monologues in the voices of Japanese citizens effected by the disaster were fictional, although the details around which I built (and collaged) their narratives were all factual. For the fictional voices, I would see which facts and details (some of which were culled from personal and/or collective accounts, most of which were culled from news stories and articles) gravitated toward a particular character or voice, and would then collage them into a narrative. In the case of “miki endo as flint marko,” I wished to honor one of the heroes of the tsunami, a young woman who worked at the Disaster Prevention Office in Minamisoma and held her ground on the loudspeaker—repeatedly telling citizens to seek higher ground and run away, until she was eventually swept away by the tsunami. Numerous people in Minamisoma credited her with saving their lives. Her monologue is told from beyond the grave, however, and in that sense, is largely fictional aside from the circumstances of her heroism during the tsunami, of course. In the case of “radiation man,” I conflated stories of two men who stayed behind in the nuclear exclusion zone (the “No Go Zone”) to care for pets and farm animals who had been left behind.

While on the one hand, I wanted to embody and give face to what I feel can be problematic erasures of identity into commodifiable and clichéd spectacles of victimhood and survivorhood—a flattening of self and subject into other and objecthood—at the same time, I also feel that trauma is a time of great vulnerability that also should be accorded privacy. This is what, in part, motivated me, I think, to make these highly-stylized monologues through using the semi-transparent masks of superheroes as conduits for the personas in the poems.

UtSQ:

she’s a mega-tsunami of pure hubris

cross-dressed in high femme

splashy / shiny / crystalline

all liquid curve and fluid light

with her Hello Kitty barrettes

pink glitter ribbons furbelowing

all that snaky girlzilla hair

bored now, she pouts in her little girl voice

before it all goes to shit

—from “beautiful tsunami”

I was struck by how you personified the tsunami, so that “she” became a fully-realized antagonist. Can you describe your process for giving voice to the tsunami?

LAR: I knew from the outset that I wanted Tsunami to be fluid, shapeshift-y, prismatic, and multifaceted. I also knew that I wanted her (and because she is made of water, I always envisioned her as originally presenting as femme, but ultimately being somewhat genderfluid and/or non-binary) to be a complex annihilatrix, like Magneto from the X-Men, whose actions are frequently destructive, even while his intentions are noble. Also, like Magneto, whose superpowers manifested during the trauma of the Holocaust, I wanted Tsunami to be forged through trauma—although, in her case, the trauma is literally the fault-line in the ocean floor causing the earthquake that gives rise to a tsunami. Of course, the challenge was how does one give voice to a powerful and destructive force of nature? And I think the answer, for me, was that Tsunami couldn’t be encapsulated through a single, first-person voice. That would be too reductive. Through using third-person omniscient, however, Tsunami could become a multifaceted series of shifting projections—a polyvocal mirroring of human desires and fears.

UtSQ: I can only imagine that delving so intensely into the circumstances of this tragedy and its ongoing aftermath was challenging on a spiritual level. From a craft standpoint, I’m curious how this affected your ability to give voice to the trauma. Was there a piece that posed a specific challenge? Was there a poem that arrived “easiest” on the page?

LAR: This is such a great question. As you know, my previous book, Dandarians, was intensely confessional, and intensely, sometimes painfully, personal. Moving from the microcosm of private or personal trauma into the macrocosm of public and national trauma was interesting. There are some commonalities, of course, but also obviously some dangers, as well—particularly, I think, in terms of wanting to be very respectful in terms of how I handled traumatic experiences that ultimately belonged to people other than myself. I think this is why I began by writing the third-person Tsunami poems. As an entity, she was in many respects a creative blank slate, and when I envisioned her as being created by trauma, I found that the trauma I imagined her being informed by was most frequently sexual, physical, and emotional violence or abuse. Some of these projections or experiences were my own, of course, but in a greater sense, these also felt like larger cultural projections emanating from female and non-binary subjects. It felt as if there was a rising tide of justifiable anger in the air at the time I began writing the Tsunami poems, and there was something very cathartic/cleansing in being able to give voice to an all-powerful entity in solidarity with a building chorus of female and non-binary voices tripping over the faultline of cultural misogyny and empire.

The most difficult poems for me to write, I think, were the monologues “hisako’s testimony” and “hulk smash”—perhaps because they encapsulated some of the narratives of the most vulnerable of the Fukushima victims/survivors. Although I had conceived of these voices/characters early on during the stage of drafting the Fukushima 50 monologues, I resisted writing these two until the very end, and afterwards, I felt emotionally wrecked. I’ve read “hulk smash” a number of times at readings, and it’s an intense experience, but I’ve read “hisako’s testimony” only once so far because it’s such a painfully difficult narrative for me.

UtSQ:

/ 200

pounds apiece of radioactive boars

bulldozing down the farmland

with glow-in-the-dark hooves

and contaminated snouts / mutant

super boars / new syndicate

of the no go zone / smarter

than charlotte / demagogues

of their own brutal animal farm

—from “song of the mutant super boars”

Your writing often revels in the grotesque, so I was not surprised to discover that this book explores nature’s incongruence with technology and nature’s attempt to survive what humankind has destroyed, dabbling with an idea similar to what Joyelle McSweeney has dubbed the Necropastoral. How do you see your use of the super hero trope fitting into this thought process? What do you hope your work evokes by employing these references?

LAR: Yes, this book is definitely circling around ideas of the Necropastoral and the grotesqueries that result when technology either collides with, or attempts to control, nature. I think that superheroes, particularly in incarnations that are the result of radioactive accidents, are frequently grotesques—beginning with the giant mutant monsters such as Godzilla, Mothra, and Hedora, et al., who rise on Monster Island. But even stretchy, rubbery-limbed Reed Richards of the Fantastic Four, or the Amazing Hulk, or Spider Man (who’s bit by a radioactive spider) are all also grotesque in their own way. And of course, Tsunami herself seems like a harbinger, or hastener, even, for the Anthropocene—not only in terms of her terrible swathe of destruction, but in the ways that she topples the poisonous and contaminating edifices of humankind.

UtSQ: Although your ultimate goal (and achievement) was to commemorate those effected by the tsunami and the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, what did you personally take away from the experience of writing and then publishing these poems?

LAR: At the time that I first began writing and publishing these poems it was still the pre-Trump era, pre-#MeToo, pre-#NoDAPL, and #BlackLivesMatter was a nascent movement following Trayvon Martin’s murder in 2012. What I was feeling at the time was a kind of seismic unease, I think, that became increasingly embodied in the rising tide of social justice movements that have formed since 2011. I feel as if, in addition to commemorating and honoring the tsunami and Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, the book has also become a way to articulate some of the environmental terrors of the Anthropocene. I also like to think of Tsunami—as an all-powerful femme/non-binary entity—as being symbolic of a force that (literally) dismantles, deconstructs, and decolonizes the Westernized edifices of patriarchy and empire. And I love that about her.

Lee Ann Roripaugh is the author of five volumes of poetry: tsunami vs. the fukushima 50 (Milkweed Editions, 2019), Dandarians (Milkweed, Editions, 2014), On the Cusp of a Dangerous Year (Southern Illinois University Press, 2009), Year of the Snake (Southern Illinois University Press, 2004), and Beyond Heart Mountain (Penguin, 1999). She was named winner of the Association of Asian American Studies Book Award in Poetry/Prose for 2004, and a 1998 winner of the National Poetry Series. The current South Dakota State Poet Laureate, Roripaugh is a Professor of English at the University of South Dakota, where she serves as Director of Creative Writing and Editor-in-Chief of South Dakota Review.