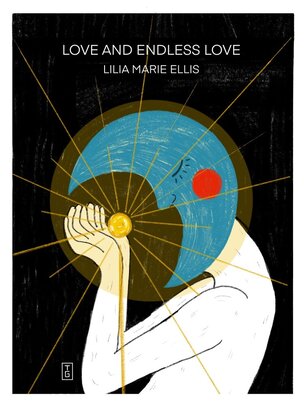

Love and Endless Love by Lilia Marie Ellis

Love and Endless Love by Lilia Marie Ellis

Digital: 17 pages

Publisher: giallo lit, 2021

Purchase @ giallo lit

Digital: 17 pages

Publisher: giallo lit, 2021

Purchase @ giallo lit

Review by Rachel Stempel.

“why strive for perfection when Earth itself is broken”

In her National Book Critics Circle Award acceptance speech for the poetry collection, The Carrying (Milkweed Editions, 2018), Ada Limón quoted Muriel Rukeyser: “What would happen if one woman told the truth about her life? The world would split open.” More recently, Limón reflected on this homage in a piece for LitHub:

“In an interview someone asked me why I chose to talk about Muriel Rukeyser rather than Plath or Sexton and I said, ‘Because she lived.’ I worry about how we celebrate women poets who committed suicide young. Is it because they don’t have bodies anymore? Is it easier to love a woman who cannot talk back? Cannot be more than words on a page? Cannot age in a body?”

“Because she lived” sat at the forefront of my mind as I read trans poet Lilia Marie Ellis’ debut microchapbook, Love and Endless Love. This tiny collection confronts Limón’s concerns head on. With a stylized voice reminiscent of yesteryear’s greats and the spunk and precision of a technoculture manifesto, Ellis captures the intangible in only eleven poems.

“I did think it lovely and almost it was”

With hardly any end punctuation, Ellis’ intertextual prose poems melt into one another, every sentiment aware of and embracing its potential for opposition. This collection is very much a work in constant flux. I’ve revisited it the text—all 17 pages of it—four times, and each read is a not a reintroduction but its own distinct experience.

It’s easy to get lost in the sea of em dashes, commas and semicolons I’ve come to expect of Ellis’ work. The hypnotic rhythm of their siren-like syntax lulls you into the “only infinity we’re capable to give.” Love and Endless Love demands of us an organic, and, of course, endless correspondence—between reader and text, between reader and the act of reading, between a “calculation” of joy and the “infinity of courages” needed “to carry on the work of living.”

“choosing my miracle recklessly as one would a horror (life too a choice made daily)”

These poems conjure a sense of undisclosed otherness, “screaming at the fact of existence.” In a moment of navel-gazing, the speaker addresses us, warning that when “a sweet voice sounding sweet tells you to imagine away the crack of Earth,” we ought not to “settle for what gives off the face of kindness.”

We ought not to fade into ourselves, either—“though it feels wrong to do so we must rejoice at the moments we’re happy to be alive.”

“[D]o you ever stop counting regrets?” we’re asked. We needn’t answer. In the aptly titled “Ode to cruelty,” Ellis writes, “I’ve no choice but to understand.” In “Participation,” we’re invited to recall “not memory itself but the work it took.” Ultimately, Ellis reveals, “I have many regrets and only some are people.”

I hesitate to use the word “inspirational” to describe these poems. Doing so would detract from the gritty moments and intense clarity of thought that Ellis expertly weaves between a calculated and roundabout repetition. A line like, “there’s no way to spill it out you can’t fucking escape there is no way out the pressure keeps fucking building,” precedes another like, “once i asked myself how could there be any gods in this wretched place now i ask myself why, given it is so wretched, it is so beautiful.” Is this inspirational? Does Ellis intend to inspire? Or, are they telling the truth about their life, splitting the earth open first for themselves, and then for anyone else who will listen?

“I mean how tireless it goes … (this poem will not end)”

“why strive for perfection when Earth itself is broken”

In her National Book Critics Circle Award acceptance speech for the poetry collection, The Carrying (Milkweed Editions, 2018), Ada Limón quoted Muriel Rukeyser: “What would happen if one woman told the truth about her life? The world would split open.” More recently, Limón reflected on this homage in a piece for LitHub:

“In an interview someone asked me why I chose to talk about Muriel Rukeyser rather than Plath or Sexton and I said, ‘Because she lived.’ I worry about how we celebrate women poets who committed suicide young. Is it because they don’t have bodies anymore? Is it easier to love a woman who cannot talk back? Cannot be more than words on a page? Cannot age in a body?”

“Because she lived” sat at the forefront of my mind as I read trans poet Lilia Marie Ellis’ debut microchapbook, Love and Endless Love. This tiny collection confronts Limón’s concerns head on. With a stylized voice reminiscent of yesteryear’s greats and the spunk and precision of a technoculture manifesto, Ellis captures the intangible in only eleven poems.

“I did think it lovely and almost it was”

With hardly any end punctuation, Ellis’ intertextual prose poems melt into one another, every sentiment aware of and embracing its potential for opposition. This collection is very much a work in constant flux. I’ve revisited it the text—all 17 pages of it—four times, and each read is a not a reintroduction but its own distinct experience.

It’s easy to get lost in the sea of em dashes, commas and semicolons I’ve come to expect of Ellis’ work. The hypnotic rhythm of their siren-like syntax lulls you into the “only infinity we’re capable to give.” Love and Endless Love demands of us an organic, and, of course, endless correspondence—between reader and text, between reader and the act of reading, between a “calculation” of joy and the “infinity of courages” needed “to carry on the work of living.”

“choosing my miracle recklessly as one would a horror (life too a choice made daily)”

These poems conjure a sense of undisclosed otherness, “screaming at the fact of existence.” In a moment of navel-gazing, the speaker addresses us, warning that when “a sweet voice sounding sweet tells you to imagine away the crack of Earth,” we ought not to “settle for what gives off the face of kindness.”

We ought not to fade into ourselves, either—“though it feels wrong to do so we must rejoice at the moments we’re happy to be alive.”

“[D]o you ever stop counting regrets?” we’re asked. We needn’t answer. In the aptly titled “Ode to cruelty,” Ellis writes, “I’ve no choice but to understand.” In “Participation,” we’re invited to recall “not memory itself but the work it took.” Ultimately, Ellis reveals, “I have many regrets and only some are people.”

I hesitate to use the word “inspirational” to describe these poems. Doing so would detract from the gritty moments and intense clarity of thought that Ellis expertly weaves between a calculated and roundabout repetition. A line like, “there’s no way to spill it out you can’t fucking escape there is no way out the pressure keeps fucking building,” precedes another like, “once i asked myself how could there be any gods in this wretched place now i ask myself why, given it is so wretched, it is so beautiful.” Is this inspirational? Does Ellis intend to inspire? Or, are they telling the truth about their life, splitting the earth open first for themselves, and then for anyone else who will listen?

“I mean how tireless it goes … (this poem will not end)”

Lilia Marie Ellis (they/she) is a trans writer. Their chapbook Love and Endless Love was released this year by giallo lit. Follow them on Twitter/Instagram @LiliaMarieEllis!