All the Marys: A Review of Mary’s Dust by Melinda Mueller

- Paperback: 104 pages

- Publisher: Entre Ríos Books (2017)

- Purchase @ Entre Ríos Books

Review by Hannah VanderHart.

But we cannot regard the world without

making it a mirror. Glistening mushrooms

rise dispassionate from summer’s ruins,

out of beauty corrupted into oozing crumbs,

and we assign to them our horror.

So speaks the Mary Shelley section of Melinda Mueller’s poem “Childbed Fever,” a poem which takes the cause of Mary Wollstonecraft’s death as its title. These lines exist in a poetic, narrative space where mother connects to daughter, and writer to writer: Mary Wollstonecraft, author of A Vindication of the Right of Women, and Mary Shelly, author of Frankenstein—as well as Melinda Mueller, author of Mary’s Dust. Yet the collective, human gaze and the world-as-mirror found in these lines respond also to the cascade of names, stories, and poetics collected in Mueller’s most recent and fourth book of poetry, Mary’s Dust.

Mary, in her many forms, is the locus of the histories in Mary’ Dust. Mueller dedicates the book:

In honor of my line of Marys:

My great-grandmother, Margaret.

My grandmother, Marjorie.

My aunt, Marcia.

&

My mother, Maralyn.

She taught me to read

and gave me the world.

I preserve the lineation and textual unity of Mueller’s dedication because this is a collection of poetry as deeply concerned with poetic form as it is with matrilineal inheritances, successions, and genealogies. Marys (Margaret, Marjorie, Marcia, Maralyn and more) form the musical core of the histories Mueller reveals in Mary’s Dust--they are both the collection’s method and its music.

Mary’s Dust opens with the poem “Annunciation,” arguably the most famous Mary story there is. This poem acts as an invocation to each woman’s story—as though each Mary in the text encounters her own, individual “angel, blazing.” The poem addresses the telling of stories, “She could not have told / what was said,” and a reality of much history-telling and scholarship: “The story was / / conceived years later, by men / who had not been there.” Against a male “conception” of women’s stories, Mary’s Dust offers its reader a poetic compendium of women’s narratives (scientists, spies, surgeons, writers) both told and written by a woman.

Each Mary strikes the reader as particularly called to the text, however, and Mueller responds to their particularity with a lyrical, historical focus on craft. Maria Aegyptica’s poem “The Lost Gospel of Maria Aegyptica,” is told with marginal notations associated with scriptural texts (1:17, 1:18). “Mariyah the Copt,” written in elliptical fragments that reflect Mariyah’s absent birth/death dates (“b.? […] d.?”), recollects Sappho’s fragments (especially Anne Carson’s translation, If not, Winter). “Stagecoach Mary,” about the first US, African-American woman star route mail carrier, employs ballad meter: “The wind was a wolf; The wolves were a gale / The snow was as cold as the stars.” Mueller’s writing formally shimmers as she moves between dramatic forms and textures of documentary texts (newspapers, trial transcripts, testimonies, field guides). A particularly riveting execution of dramatic staging can be seen in the poem “Mary Easty,” about a woman hung as a witch in Salem. The poem moves backwards through time, decay and death, creating its narrative tension through the drama and liveliness of story and history.

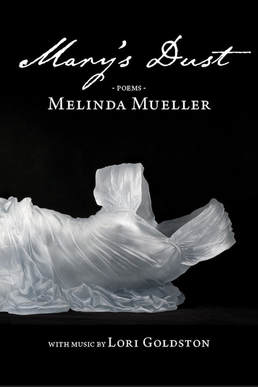

The historical and artistic scope of Mary’s Dust is wide and collaborative—for example, the suite of five cello songs composed and performed by Lori Goldston, accessible as audio accompaniment to Mary’s Dust, or the artwork by Karen Lamonte on the cover and endpapers. On the note of scope, I want to say a word about Mueller’s narrative selection, or methodology. Mueller’s Marys includes women of different times, nations, races and class. This is not a white-washed collection of lyric-narratives—rather, Mueller’s work enacts historical-poetic recovery. Mary’s Dust is a stay against that particularly American vice contemporary historians discuss: amnesia (in this case, the individual histories of slaves and the achievements of persons of color). Mueller does not let us forget, but weaves her poetry as tapestries, so that we can also look and see. The Marys of color appearing in Mueller’s poems include Mary Prince, born into slavery in Bermuda; Mary Elizabeth Bowser, born a slave, freed, and served as a spy in Jefferson Davis’s household; Marie Laveau, a “free woman of color” and “voodoo queen” living in New Orleans; “Stagecoach Mary” Fields, born a slave in TN around 1832, and Sister Mary Makukutsi, a catholic nun and nurse Mueller met in Zambia. Mueller’s poetry extends annunciation and calling across many Marys, demonstrating how inclusivity brings power and persuasion to poetry, history and storytelling.

A poem illustrating Mueller’s understanding of the genealogy and narratives of the Marys is the poem “Ledger,” which opens:

Suppose each star were named.

Suppose as each burnt down to cinders

someone mourned.

Suppose each scrap of paper

swirling through the streets

sang like a bird, suppose it spoke

the final words that fell

across its surface. Suppose

smoke had a memory.

Suppose it had a voice.

Suppose someone was listening,

someone with a pen and ink

and paper. Suppose there was

a list and that the clouds

could read it. Suppose they

broadcast it into space. Names

of stars. Names of birds. Names

called and no one answers.

“Suppose,” the poem asks, nine times, proposing a hypothesis of memory, commemoration, memorial—words bound to each other and the project of Mary’s Dust. The act of memory and re-membering are intrinsic to the storytelling of Mary’s Dust—to its griefs and celebrations, to its “just and loving gaze,” to borrow a concept of attention from the great Irish writer and philosopher, Iris Murdoch. A longing for such attention and narrative presence is the heart of the poem “Ledger,” which asks, “And if the day is dreary and smudged / who will claim it?” The poem closes on its answer, “Ai Ai Ai / cry the voiceless dead reaching out / with their no hands.” Mueller’s end notes are an incredible work in themselves—often lengthy, delving into the lives behind the individual poems. Her end note to “Ledger” is simple, elegant: a block list of the full names of every Mary who died on September 11, 2001.

The poems of Mary’s Dust mourn, celebrate, listen and inscribe the histories of an assembly of women. The poems themselves answer the “suppose” wondered in “Ledger”—because of the lives, gifts and tragedies they embody, the narratives of the Marys do not go to dust, but are, as the last line of the poem “Annunciation” declares: “ringing, as if it were the dust / of a thousand bells.

Hannah VanderHart lives and teaches in Durham, NC. She is currently at Duke University writing her dissertation on gender and collaboration poetics in the seventeenth century. She has poems recently published and forthcoming at Cotton Xenomorph, The McNeese Review, Unbroken Journal, Thrush, and Glass: A Journal of Poetry. More at: hannahvanderhart.com