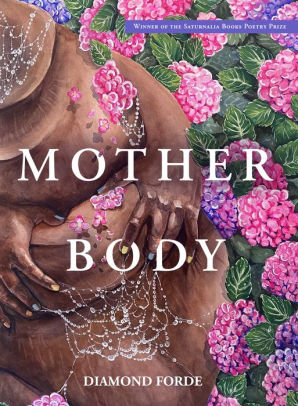

Mother Body by Diamond Forde

Mythology & Intersectionality in Mother Body

Review by Alina Stefanescu.

Imagine that every god you know is lying, and every image you consume is a distraction from the wonder of surviving inside the female body. Now you are ready to sink into Diamond Forde's opulent Mother Body. You are ready to join the poet in circling this body carefully, lovingly, tenderly, with the eye of god who knows herself in its lineage.

*

Diamond Forde has named Dorianne Laux, Sharon Olds, Lucille Clifton, Donika Kelly, and Patricia Smith as poets who gave her "permission to be a woman who could inhabit her whole body." Permission to inhabit the woman's body is fabric for Forde's ongoing work, including a dissertation seeking to retell Old Testament books from the perspective of her maternal history (evoked in the "The Fourth Book of Alice Called Family Tree"). Refusing to participate in the alienation of abstracted pain, Forde's poems carry both pain and pleasure in embodiment. No emotion lays outside the flesh; no aspect of incarnate is shamed through elision or quiet erasure. Forde is not here for the symphonies of stoicism or avoidance: she is here for the reincarnation, the pulsed-open poem.

She begins this prize-winning collection with a repurposed ode, a framing poem set outside the sections, an invocation of kinship with Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, Ahmaud Abery, and other recent Black lives lost to police brutality. "Blood Ode" takes the ode as lament, reaching back into the Greek tradition where odes and elegies inhabited the shared space of honoring lost heroes. The poem reveals how the gaze, itself, mothers the eye, or renders the looking, maternal.

*

In "Ode to My Neighbors," the word would've works as anaphora, building motion and friction into the sound of neighbors having sex. The sensuality of Forde's lyric foregrounds the female body, the questions of what this body is asked to carry, in this case, the juxtaposition of physical pain and the reality of Black trauma appearing in headlines, and in the poet's body when going to the store to get toilet paper after Charlottesville. The narrator speaks from inside the parked car, immobilized by fear and by the pain held in the body.

The relationship between the breath, or breathing, and the Black body, is central to "Breathe Ode," where Momma taught her "to breathe slow / in the blue bar of a cop's light." Forde rejects the metaphor of breath offered by her mom, the one for whom guilt and fear look the same. This is an ode to her breath in long, swooning tercets which insist on loving her "breath's every elaborate shape," and this love for the breath, for the body, undone by what the world makes of it.

The notion of lineage and inheritance presupposes the mother, the wombed vessel deputized to carry children. In trying to understand this maternal gaze--and the brilliance with which Forde subverts the idolatry of wombs as vessels for inheritance--I followed the incubated expectations, the internalizations juxtaposed alongside myths, and discovered Gaia.

*

In Greek mythology, Gaia is the personification of the Earth itself, the mother to all gods, titans, and monsters, and wife to her son, Ouranos. More recently, ecofeminist thought has moved towards a female-gendered spirituality that focuses on immanence rather than transcendence. Gaia, this idea of the sacred earth, presents a goddess who is coextensive and one with the planet, as opposed to the Judeo-Christian God who stands above, and aloof, from it. Ecofeminism turns the biological prison of the wombed body on its head by revisioning limitations in a positive light, elevating caretaking, nurture, tenderness, birth, and embodiment into a source of holiness inseparable from the linked relations of all life. Rather than owning, naming, taming, and binding, Gaia opens, tends, celebrates, gives life. In this immanence, she (and we) are sacred.

However, the challenge of essentialism lies in making sacrifice part of the patriarchal expectation. If Forde uses Gaia as an entryway into motherbodies, she takes on Western patriarchal mythology by challenging what the motherbody owes this world--and what she celebrates by taking from it.

"Gaia Gets Down at a House Party" takes its character from Derrick Harriell's Stripper in Wonderland. The language here liberates the body from clothing, each "twerk & torque" a raucous demand for freedom.

Even when stripped, Forde's poems dance inside the question of how to protect a body threatened both by news, racism, and the silenced medical issues related to wombs. To read Forde is kinetic, is to feel the blood's rhythm and sonic effect, to know poetry seduces by linking marvel to sound, to breath, to beat--pressing it deep inside the flesh.

Jellyfish are poetic prisms for Forde, who explores their flesh as a guide into her own, a resemblance in the way they are perceived as threatening, or in the cultural disgust they can elicit. "Jellyfish Ballad," a gorgeous arrangement of seven quatrains, is an interior monologue which asks the self why she cannot quite "revile" her body, despite the world which makes arguments for it. Forde articulates:

A self-love, resistant,

snaps in the synapse like the spark

between finger and nematocyst.

The sibilance of the second line--the energy exchanged between snaps, synapse, and spark--sets up the crack in the simile. Reading these poems at the level of the line is like watching someone land a triple backflip off a beam: the image sears to your mind. I could not get used to the dexterity Forde brings to language, in the shifts between slowness and crackle, as in "The Last Time I Saw My Grandfather," which begins:

he told me was glad I wasn't fat yet

but this time, with flesh glutinous on my arms and back,

hips spread like grain, I wax at his bedside and watch

Standing at her grandfather's deathbed, his words circle her body like a tape measure, but the narrator refuses the critique by describing herself in full spectrum of fleshness; she is glutinous (a slip of the tongue from "mutinous"), expanding like a moon in the cycle of ripening. This small thing--the use of a lunar verb--changes the interior landscape of this poem, laying power in the moon and the narrator's relation to it.

I wish there was a word for poems where confession meets interrogation in image, or a trope to slide over how this poem ends:

thick and gratuitous guilt. I am guilty

because I am grateful for this last, fateful chance

to disappoint him--he, who once grazed his cold hand

across my rounding cheek and prayed for bones.

And so the man who is dying, who is so thin on that bed, finds his prayer for bones unrealized in the grandaughter whose body celebrates life.

Forde develops an aesthetics of the flesh towards defiant self-love and self-succor, and this carries into "Womb Elegy," a poem addressed to the womb in a myth-laden voice evoking the head of John the Baptist on a plate, underscoring the sacrifice of the female body:

Mother, like savior

and saint, likely served on silver

platter. Daughter, gnashing

with hunger. What does she want?

if not certainty

of wholeness?

This attention to the stigmatized body is not new, but Forde brings it to bear on the industry of wellness, youth, beauty which promises completion by twelve-step program on a planet where patriarchy and racism persist in market-based myths.

*

Carving space for conversations that can't take place in real time, Forde's poems are plucked from the mouths of loved ones, lending poetry, itself, to dialogic purpose. The voices of doctors, mothers, fathers, grandparents, boyfriends--all intrude in the poems, all enter in italics, dressed up like unforgettable adages singed on the brain. The use of italics sets them apart but also sacralizes them, sets them apart and outside the world of arguments, like litanies repeated on a rosary of things one can't forget.

"What I Have to Give", a poem that describes the business of pain, the divide between the clinical and the inhabited, the gynecologist's office, offers the womb as idol, a "false god" in the femme-pantheon. As the female doctor "scrapes" her insides, the mother's voice returns as "stones" in the wall she has built to protect herself, in the words "Your body is a temple", and the "noose" of the doctor's voice saying, "You Black girls / tend to suffer more." Pain is the narrator's "partner," the faithful presence, and the short tercets alternating between three voices--all set aside by use of italics--keep erecting walls within the body.

One could argue that Forde's use of italics pushes the lines between thinking and saying to the point of straddling it. One could argue that straddling is the most appropriate position in a language where even relief and mercy hinge on the presence of a male god. One could suspect that even the myth of Echo finds her voice in these repetitions.

In "Stripping," the narrator visits a zoo and imagines the life of a male elephant. Alliteration links the vivid images and soundscapes in the elephant portrait: "his dick chalks circles in the dirt" and "toot a chuckle from his trumpet trunk." Reducing the elephant "to the small sum of his mating parts," Forde compares her own body to that of the elephant, wishing she could tell the keepers: "Go ahead. Take exactly what you want." The intimate, interior first-person voice pushes this line between thinking and saying by use of italics.

"Hysterectomy" is immaculate, a deconstructed bop form borrowed from Afaa Michael Weaver where the poetic argument occurs across threat stanzas followed by refrain. Forde's refrain begins as a couplet: the first time makes use of a linked rhyme, connecting the last syllable of one line with the first syllable of the next one.

to do the violence I want

and still be loved for it.

Across uneven stanzas, the idea of motherhood "holds me whole" in the expectation of child-bearing, a fulfillment where the uterus serves as "hero for someone else's dreams."

To do the violence I want and still be

loved for it.

The uterus is "collateral," a bargaining chip to soothe "women who pray for children." The ragged stanzas continue before ending with the couplet breaking down, expanding the refrain into a five line stanza one hears as a slow wail:

To do the violence

I want

I want

I want

and still be--

The use of rhyme creates musicality and tempo, and Forde's repetition gave me goosebumps. As do the interline rhymes at the beginning of "Trying to Write A Music Poem," and divine threadwork of irregular rhymes throughout these poems.

*

In a series of poems narrated by "Fat Girl," Forde puts pressure against the culture that monetizes fullness into self-loathing and guilt. I thought of Claudia Cortese and other poets doing the work of revealing how fatness is treated, internalized, and turned into expertise. "Fat Girl" is a descriptor, a qualifier, and Forde titles the poems as vignettes, brief forays into what "Fat Girl" does.

In "Fat Girl Confuses Food & Therapy Again," the narrator sneaks to the fridge at midnight, doing what we all do, savoring life, insisting on its sensuality. I kept thinking about how diet culture punishes lushness, or holds back from the lush body what is lush in the mouth.

"Fat Girl Reads Mythology On a Friday Night" returns to Gaia, "naked in the lamp light," an archetypal spirit:

Gaia is world-wide & wide, fat girl loves her

with the tepid humidity of a mother's want.

In Greek mythology, the narrator finds the hecantoncheires, or hundred-handed-ones, and she wants to be "clutched in furious love" by those hundred hands, to find herself touched. "Fat Girl Is Obsessed with Jellyfish" revisits a beach in November with her mother, The water too cold, the metaphor between desiring and becoming one "whose vortices of stingers/ circle cyclones around her neck like pearls." The poem ends in the question of how fat could resist the gorgeous world which touches her, the poem which emerges from a medusa?

The metaphor of body as ocean appears in "Fat Girl Dances with a Stranger at a Block Party," where

fat girl grinds on anybody who wants to learn

how to praise the ocean.

Or how to "cradle her rock-a-bye hips with ritual awe."

Ending with "Fat Girl Climaxes While Working Out At the Gym," the narrator, who is listening to a song by Cardi B., takes us inside the meeting space of all public body-inflected opposites and tensions, the complexity of sex, pleasure, appetite, desire, physicality, and flesh. Incredible figurative language that torques and twists--less oceanic than snappy, urgent, immediately manifest: "and pussy, you are the only me I've loved regardless." The pussy is the addressee, the orgasmic source of "this light and lyric." No one looks up from machine or mirror to see this paean to pleasure unfold in the body, wanting to taste life, savor every raw stich of it.

Review by Alina Stefanescu.

Imagine that every god you know is lying, and every image you consume is a distraction from the wonder of surviving inside the female body. Now you are ready to sink into Diamond Forde's opulent Mother Body. You are ready to join the poet in circling this body carefully, lovingly, tenderly, with the eye of god who knows herself in its lineage.

*

Diamond Forde has named Dorianne Laux, Sharon Olds, Lucille Clifton, Donika Kelly, and Patricia Smith as poets who gave her "permission to be a woman who could inhabit her whole body." Permission to inhabit the woman's body is fabric for Forde's ongoing work, including a dissertation seeking to retell Old Testament books from the perspective of her maternal history (evoked in the "The Fourth Book of Alice Called Family Tree"). Refusing to participate in the alienation of abstracted pain, Forde's poems carry both pain and pleasure in embodiment. No emotion lays outside the flesh; no aspect of incarnate is shamed through elision or quiet erasure. Forde is not here for the symphonies of stoicism or avoidance: she is here for the reincarnation, the pulsed-open poem.

She begins this prize-winning collection with a repurposed ode, a framing poem set outside the sections, an invocation of kinship with Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, Ahmaud Abery, and other recent Black lives lost to police brutality. "Blood Ode" takes the ode as lament, reaching back into the Greek tradition where odes and elegies inhabited the shared space of honoring lost heroes. The poem reveals how the gaze, itself, mothers the eye, or renders the looking, maternal.

*

In "Ode to My Neighbors," the word would've works as anaphora, building motion and friction into the sound of neighbors having sex. The sensuality of Forde's lyric foregrounds the female body, the questions of what this body is asked to carry, in this case, the juxtaposition of physical pain and the reality of Black trauma appearing in headlines, and in the poet's body when going to the store to get toilet paper after Charlottesville. The narrator speaks from inside the parked car, immobilized by fear and by the pain held in the body.

The relationship between the breath, or breathing, and the Black body, is central to "Breathe Ode," where Momma taught her "to breathe slow / in the blue bar of a cop's light." Forde rejects the metaphor of breath offered by her mom, the one for whom guilt and fear look the same. This is an ode to her breath in long, swooning tercets which insist on loving her "breath's every elaborate shape," and this love for the breath, for the body, undone by what the world makes of it.

The notion of lineage and inheritance presupposes the mother, the wombed vessel deputized to carry children. In trying to understand this maternal gaze--and the brilliance with which Forde subverts the idolatry of wombs as vessels for inheritance--I followed the incubated expectations, the internalizations juxtaposed alongside myths, and discovered Gaia.

*

In Greek mythology, Gaia is the personification of the Earth itself, the mother to all gods, titans, and monsters, and wife to her son, Ouranos. More recently, ecofeminist thought has moved towards a female-gendered spirituality that focuses on immanence rather than transcendence. Gaia, this idea of the sacred earth, presents a goddess who is coextensive and one with the planet, as opposed to the Judeo-Christian God who stands above, and aloof, from it. Ecofeminism turns the biological prison of the wombed body on its head by revisioning limitations in a positive light, elevating caretaking, nurture, tenderness, birth, and embodiment into a source of holiness inseparable from the linked relations of all life. Rather than owning, naming, taming, and binding, Gaia opens, tends, celebrates, gives life. In this immanence, she (and we) are sacred.

However, the challenge of essentialism lies in making sacrifice part of the patriarchal expectation. If Forde uses Gaia as an entryway into motherbodies, she takes on Western patriarchal mythology by challenging what the motherbody owes this world--and what she celebrates by taking from it.

"Gaia Gets Down at a House Party" takes its character from Derrick Harriell's Stripper in Wonderland. The language here liberates the body from clothing, each "twerk & torque" a raucous demand for freedom.

Even when stripped, Forde's poems dance inside the question of how to protect a body threatened both by news, racism, and the silenced medical issues related to wombs. To read Forde is kinetic, is to feel the blood's rhythm and sonic effect, to know poetry seduces by linking marvel to sound, to breath, to beat--pressing it deep inside the flesh.

Jellyfish are poetic prisms for Forde, who explores their flesh as a guide into her own, a resemblance in the way they are perceived as threatening, or in the cultural disgust they can elicit. "Jellyfish Ballad," a gorgeous arrangement of seven quatrains, is an interior monologue which asks the self why she cannot quite "revile" her body, despite the world which makes arguments for it. Forde articulates:

A self-love, resistant,

snaps in the synapse like the spark

between finger and nematocyst.

The sibilance of the second line--the energy exchanged between snaps, synapse, and spark--sets up the crack in the simile. Reading these poems at the level of the line is like watching someone land a triple backflip off a beam: the image sears to your mind. I could not get used to the dexterity Forde brings to language, in the shifts between slowness and crackle, as in "The Last Time I Saw My Grandfather," which begins:

he told me was glad I wasn't fat yet

but this time, with flesh glutinous on my arms and back,

hips spread like grain, I wax at his bedside and watch

Standing at her grandfather's deathbed, his words circle her body like a tape measure, but the narrator refuses the critique by describing herself in full spectrum of fleshness; she is glutinous (a slip of the tongue from "mutinous"), expanding like a moon in the cycle of ripening. This small thing--the use of a lunar verb--changes the interior landscape of this poem, laying power in the moon and the narrator's relation to it.

I wish there was a word for poems where confession meets interrogation in image, or a trope to slide over how this poem ends:

thick and gratuitous guilt. I am guilty

because I am grateful for this last, fateful chance

to disappoint him--he, who once grazed his cold hand

across my rounding cheek and prayed for bones.

And so the man who is dying, who is so thin on that bed, finds his prayer for bones unrealized in the grandaughter whose body celebrates life.

Forde develops an aesthetics of the flesh towards defiant self-love and self-succor, and this carries into "Womb Elegy," a poem addressed to the womb in a myth-laden voice evoking the head of John the Baptist on a plate, underscoring the sacrifice of the female body:

Mother, like savior

and saint, likely served on silver

platter. Daughter, gnashing

with hunger. What does she want?

if not certainty

of wholeness?

This attention to the stigmatized body is not new, but Forde brings it to bear on the industry of wellness, youth, beauty which promises completion by twelve-step program on a planet where patriarchy and racism persist in market-based myths.

*

Carving space for conversations that can't take place in real time, Forde's poems are plucked from the mouths of loved ones, lending poetry, itself, to dialogic purpose. The voices of doctors, mothers, fathers, grandparents, boyfriends--all intrude in the poems, all enter in italics, dressed up like unforgettable adages singed on the brain. The use of italics sets them apart but also sacralizes them, sets them apart and outside the world of arguments, like litanies repeated on a rosary of things one can't forget.

"What I Have to Give", a poem that describes the business of pain, the divide between the clinical and the inhabited, the gynecologist's office, offers the womb as idol, a "false god" in the femme-pantheon. As the female doctor "scrapes" her insides, the mother's voice returns as "stones" in the wall she has built to protect herself, in the words "Your body is a temple", and the "noose" of the doctor's voice saying, "You Black girls / tend to suffer more." Pain is the narrator's "partner," the faithful presence, and the short tercets alternating between three voices--all set aside by use of italics--keep erecting walls within the body.

One could argue that Forde's use of italics pushes the lines between thinking and saying to the point of straddling it. One could argue that straddling is the most appropriate position in a language where even relief and mercy hinge on the presence of a male god. One could suspect that even the myth of Echo finds her voice in these repetitions.

In "Stripping," the narrator visits a zoo and imagines the life of a male elephant. Alliteration links the vivid images and soundscapes in the elephant portrait: "his dick chalks circles in the dirt" and "toot a chuckle from his trumpet trunk." Reducing the elephant "to the small sum of his mating parts," Forde compares her own body to that of the elephant, wishing she could tell the keepers: "Go ahead. Take exactly what you want." The intimate, interior first-person voice pushes this line between thinking and saying by use of italics.

"Hysterectomy" is immaculate, a deconstructed bop form borrowed from Afaa Michael Weaver where the poetic argument occurs across threat stanzas followed by refrain. Forde's refrain begins as a couplet: the first time makes use of a linked rhyme, connecting the last syllable of one line with the first syllable of the next one.

to do the violence I want

and still be loved for it.

Across uneven stanzas, the idea of motherhood "holds me whole" in the expectation of child-bearing, a fulfillment where the uterus serves as "hero for someone else's dreams."

To do the violence I want and still be

loved for it.

The uterus is "collateral," a bargaining chip to soothe "women who pray for children." The ragged stanzas continue before ending with the couplet breaking down, expanding the refrain into a five line stanza one hears as a slow wail:

To do the violence

I want

I want

I want

and still be--

The use of rhyme creates musicality and tempo, and Forde's repetition gave me goosebumps. As do the interline rhymes at the beginning of "Trying to Write A Music Poem," and divine threadwork of irregular rhymes throughout these poems.

*

In a series of poems narrated by "Fat Girl," Forde puts pressure against the culture that monetizes fullness into self-loathing and guilt. I thought of Claudia Cortese and other poets doing the work of revealing how fatness is treated, internalized, and turned into expertise. "Fat Girl" is a descriptor, a qualifier, and Forde titles the poems as vignettes, brief forays into what "Fat Girl" does.

In "Fat Girl Confuses Food & Therapy Again," the narrator sneaks to the fridge at midnight, doing what we all do, savoring life, insisting on its sensuality. I kept thinking about how diet culture punishes lushness, or holds back from the lush body what is lush in the mouth.

"Fat Girl Reads Mythology On a Friday Night" returns to Gaia, "naked in the lamp light," an archetypal spirit:

Gaia is world-wide & wide, fat girl loves her

with the tepid humidity of a mother's want.

In Greek mythology, the narrator finds the hecantoncheires, or hundred-handed-ones, and she wants to be "clutched in furious love" by those hundred hands, to find herself touched. "Fat Girl Is Obsessed with Jellyfish" revisits a beach in November with her mother, The water too cold, the metaphor between desiring and becoming one "whose vortices of stingers/ circle cyclones around her neck like pearls." The poem ends in the question of how fat could resist the gorgeous world which touches her, the poem which emerges from a medusa?

The metaphor of body as ocean appears in "Fat Girl Dances with a Stranger at a Block Party," where

fat girl grinds on anybody who wants to learn

how to praise the ocean.

Or how to "cradle her rock-a-bye hips with ritual awe."

Ending with "Fat Girl Climaxes While Working Out At the Gym," the narrator, who is listening to a song by Cardi B., takes us inside the meeting space of all public body-inflected opposites and tensions, the complexity of sex, pleasure, appetite, desire, physicality, and flesh. Incredible figurative language that torques and twists--less oceanic than snappy, urgent, immediately manifest: "and pussy, you are the only me I've loved regardless." The pussy is the addressee, the orgasmic source of "this light and lyric." No one looks up from machine or mirror to see this paean to pleasure unfold in the body, wanting to taste life, savor every raw stich of it.

|

Diamond Forde’s debut collection, Mother Body, is the winner of the 2019 Saturnalia Poetry Prize and is forthcoming in 2021. Diamond has received numerous awards and prizes, including the Pink Poetry Prize, the Furious Flower Poetry Prize, and CLA’s Margaret Walker Memorial Prize, and Frontier Poetry’s New Poets Award. She is a Callaloo and Tin House fellow, whose work has appeared in Massachusetts Review, Ninth Letter, NELLE, Tupelo Quarterly and more. Diamond serves as the assistant editor of Southeast Review. She is a 3rd year PhD candidate at Florida State University and holds an MFA from The University of Alabama. She enjoys fish, grits, and R&B. |