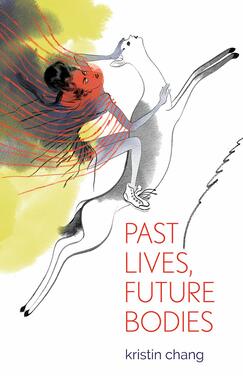

Past Lives, Future Bodies by Kristin Chang

Paperback: 46 pages

Publisher: Black Lawrence Press (2018)

Purchase @ Black Lawrence Press

Review by Travis Chi Wing Lau.

“Mourning, too, is an economy / of light.”

— Kristin Chang, from “Televangelism”

“We are a nation at ease with grievance but not with grief.”

— Anne Anlin Cheng, The Melancholy of Race: Psychoanalysis, Assimilation, and Hidden Grief

Ever since my early encounters with queer writing, I have been fascinated with the concept of melancholy1. I came to graduate school wanting to better understand this strange affective constellation and its relationship to the histories of marginalized bodies. Unsurprisingly, I first came at the question of what constituted melancholy from the vantage point of sexuality—a product of my intellectual formation during my undergraduate studies and my own personal reckonings with who I was after a decade living in the South. It took my own diagnosis with anxiety and depression during my first year of graduate school to reveal the limits of my own understanding of mental health barely talked about at the family dinner table. Alone in the affective density that was my depression, I found myself disarmed: entirely without a vocabulary with which I could describe and begin to know the nuances of my own grief, my own loss, my own unmooring.

For an experimental seminar paper during coursework, I began writing my way toward understanding what we might call racial melancholy. I conceived of this project as a critical memoir—one that interwove theory and creative nonfiction to explore the unspoken stories of depression affecting so many members of my family, including myself. This way, I could understand myself not as exception but an extension of ongoing, unresolved family trauma working through my bodymind. I remain indebted to David Eng and David Kazanjian whose co-taught course, “Race, Across Time and Space,” challenged me to think about the quotidian forms of racial experience, the way race feels. This thread of inquiry led me to their edited collection on the topic of loss, where David Eng had co-written an essay with psychotherapist Shinhee Han. I found their linking of loss and depression to “both psychic and material processes of assimilation” to be a compelling model for understanding the queer, perverse feelings of racialization animating the widespread cases of (silent) depression I was witnessing in my own family, my campus community, and in the Asian American community at large.2

In their dialogue, Eng and Han return to Freud’s 1917 “Mourning and Melancholia” as a starting point for theorizing racial melancholy. Freud distinguishes between these two psychic states by defining the former as a “successful” letting go of attachment to a particular object while defining the latter as a “failure” of the psyche to detach, which creates a pathological state of interminable mourning. For Asian Americans, such interminable mourning is born out of the struggle or failure to assimilate. Taking the form of an internalized estrangement, Asian American racial melancholy feels like an unbearable in-betweenness where ideals of whiteness or inclusion are forever “at an unattainable distance, at once a compelling fantasy and a lost ideal.”3 The model minority myth perpetuates this feeling of racial suspension by framing assimilation as not only desirable but required, while simultaneously displacing and erasing the histories and identities understood to be the necessary price to pay. These very histories and identities return as spectres: hungry ghosts haunting the “American Dream.”

In Kristin Chang’s volume, this ghostly hunger is intergenerational, intercorporeal. In scenes detailing the death of agong or the plight of her mother fleeing Taiwan during wartime, we witness the transmission of racial melancholy over time through these temporally disparate events. By navigating through different times and spaces, Chang “traces” her experiences back to “all the ways a body cannot contain itself” (46). Because racial melancholy is perpetual mourning, past trauma spills over into later generations in repeated experiences and sensations because it remains unresolved. As Chang herself experiences racism in the bedroom and on the street, this violence feels familiar precisely because it has already happened and continues to happen despite her own attempts at assimilating. Yet, even as she finds antecedents to her own racial melancholy, her queerness and generational difference reminds her that “what happens now in / my body means I am // alone” (32). Chang represents the process of her own painful formation as a queer Chinese American woman that involves “the imaginative loss of a never-possible perfection, whose loss the little girl must come to identify as a rejection of herself.”4

As each poem documents how her and her family’s “bodies domesticate / disaster: by swallowing // another country’s rains,” Past Lives, Future Bodies experiments with different poetic forms that can both express the thickness of racial melancholy and intervene in the traumatic experiences of racism and assimilation (1). Chang shifts from couplets to two-column narratives to sestets with an unpredictability that embodies her desire of “wanting a country to home” and a “body to hone” (4). It is this desire that forces us to read beyond the end of the line, that begs the question about what absent presences linger within spaces between stanzas. By refusing formal stability in poems like “Closet Space,” Chang demonstrates how racial melancholy is itself enjambment. Language ultimately becomes the means by which Chang can inhabit not only the queerness of her own desire but the otherwise inaccessible desires of generations before her that bear unexpected, uncanny similarities. In these pleats of time sewn together, kinship is beyond blood; it is shared affect, shared desire alive in verse.

Eight years ago, I wish I had had Chang’s book as a model for articulating what I felt then was the inexpressible. I can’t say I agree with readings of Past Lives, Future Bodies as poetic butchery that cuts its way toward the “future bodies” it imagines. The project, to me, seems far more reparative—an extended suturing that is unafraid of the blood already drawn, “of the dead [that] are still dying” (11). The sharpness that readers identify is in the verses’ insight, the incisiveness of the needle that threads together histories, bodies, and lived experiences separated by the need to survive in a nation that does not want us. Chang’s queer method of “unstitching this country / along its rivers, this body / shrugging free of its seams” is a poetic indictment of a delusional national narrative obsessed with inherent greatness. The feelings of suspension, of failure that keep alive this narrative are lived out in bodies of color. Melancholy is still mourning.

There must be an unraveling before future bodies can be sewn.

_________________________________

1For more on my formative experiences with queer literature, see https://medicalhealthhumanities.com/2018/01/15/revisiting-aids/.

2“A Dialogue on Racial Melancholia.” Loss: The Politics of Mourning. eds. David L. Eng and David Kazanjian. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003. 343-371.

3Eng, Han 345.

4The Melancholy of Race: Psychoanalysis, Assimilation, and Hidden Grief. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2001. 17.

Kristin Chang’s work has been published in Teen Vogue, The Rumpus, The Margins (Asian American Writers Workshop), the Shade Journal, and elsewhere. Her work has been nominated for Best New Poets and Best of the Net, and she has been anthologized in Bettering American Poetry Vol. 3 and Ink Knows No Borders(Seven Stories Press). She is a 2018 Gregory Djanikian Scholar (selected by The Adroit Journal), the recipient of a 2019 Pushcart Prize, and a Resist/Recycle/Regenerate fellow with the Wing On Wo Project in Manhattan Chinatown. Past Lives, Future Bodies is her first chapbook.