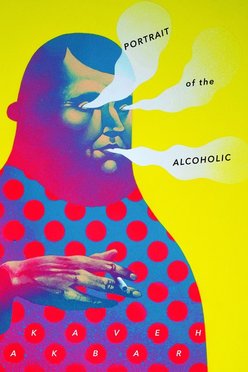

Portrait of the Alcoholic by Kaveh Akbar

Paperback: 48 pages

Publisher: Sibling Rivalry Press (2017)

Purchase @ Sibling Rivalry Press

Review by Travis Chi Wing Lau.

In 1978, Susan Sontag famously argued that “the healthiest way of being ill—is one most purified of, most resistant to, metaphoric thinking.”[1] Yet since the publication of her polemic against the stigmatizing and militaristic language surrounding illness (and later of HIV/AIDS in 1989), scholars have rightly put pressure on this narrow view of metaphor’s capacities. In what ways can metaphors be generative of new ways of being and living with illness and disability? How can metaphors by the ill and disabled reorient and expand our understandings of those experiences and what “health” can be? I come to Kaveh Akbar’s Portrait of the Alcoholic precisely for what it might teach us about addiction’s metaphoric possibilities.

Disability scholarship and activism have long resisted the medical model of disability, which is characterized by a curative impulse to fix or even eliminate disability all together. Underpinning this impulse are assumptions about what constitutes the normal, the natural, and the healthy. Recently, scholars have turned their attention to addiction to consider how it might be imagined beyond the limiting framework of pathology that frames addiction as a state of insatiable lack. I follow this line of thinking to read the Portrait of the Alcoholic as a text that actively resists the curative through a desire to inhabit and reinhabit the seemingly irreconcilable contradictions of alcohol addiction.

Akbar’s collection begins with a prefatory poem, “Some Boys Aren’t Born They Bubble,” which situates the text within what Akbar himself has called a narrative of “recovery”:

some boys aren’t born they bubble

up from the earth’s crust land safely around

kitchen tables green globes of fruit already

in their mouths when they find themselves crying

they stop crying these boys moan

more than other boys they do as desire

demands when they dance their bodies plunge

into space and recover the music stays

in their breastbones they sing songs (11)

As opposed to a straightforward narrative of development and recovery, these boys do not begin ab ovo (“aren’t born”), but rather, they emerge spontaneously into being (“bubble up from the earth’s crust”) rife with “desire.” It is in this state of intense desire that these bodies counterintuitively “recover.” Hardly the stereotypical figure of the addict whose indulgence in the desire to “lick or be licked” is excessive, these boys “sing songs” with the music that they embody; the addict’s pleasure is unexpectedly productive. Even in this opening poem, Akbar begins to modulate an understanding of addictive desire from deviance to effervescent possibility. Addiction is instead a state of imminence that resists a linear time, what Akbar later describes in “Portrait of the Alcoholic Three Weeks Sober” as a “forward [that] seems too chronological” (29).

The temporality of addiction is equally unpredictable and unbound by conventional structures of time: “temptation rarely warns you / a useful model unpredictable as an arrow through the spine / its flightpath its feathery hole who among us hasn’t wished to burst” (30). Akbar’s poems offer us a model of “sick time” that flies in the face of a conventional medical model of diagnosis, treatment, and recovery. Like the boys who “bubble,” addiction is represented through figures in motion rather than through stagnancy – fluctuating states like a flying arrow. As a narrative of addiction, Akbar’s Portrait vulnerably sits with the uncomfortable ambivalence of “being in recovery.” In “Despite Their Size Children Are Easy to Remember They Watch You,” Akbar writes,

to live well is easy a flea leaps and is unshocked by its flight

for others it’s harder and hardly seems worth doing the better a life

the more sadness it leaves… (30)

For Akbar, the assumption that healthiness is necessarily better is a false one. Though he may be on the path toward sobriety, that path is not direct or clear. In fact, the pressure “to live well” can feel “hardly worth doing,” especially when enforced by a medical establishment who is ultimately uninterested in the comparatively “healthy and unremarkable” or those “dying at an average pace” (19). If states of health remain so precarious and relative to individuals, Akbar questions why we fetishize “living well” as central to a eudemonic life worth living. Can addicts “live well”?

By the volume’s conclusion, we are left to reconsider the category of “the alcoholic” all together. Throughout Portrait, Akbar plays with the limitations of language, particularly a language that might rein in the vicissitudes of addiction. “Thinking if I called a wolf a wolf I might dull its fangs,” Akbar suggests the act of naming might contain his temptations (19). Yet language and self-restraint repeatedly fail throughout his poems. I want to suggest that this performative failure leaves open an addictive potential, the risky “and yet and yet” that concludes one of my favorite poems from the collection, “Unburnable the Cold Is Flooding Our Lives.” Akbar reminds us that an addict’s relationship to addiction does not merely cease upon “recovery,” which inherently presumes a fantastical return to some originary state of health. Recovery is a kind of perverse nostalgia, an aching for a homecoming to a home that seems less hospitable and familiar than his addictive pleasures. Appropriately then, Akbar does not leave us with the comfort of resolution because after all “the boat I am building will never be done” (45).

[1] Sontag, Susan. Illness as Metaphor. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1978. 3.

Publisher: Sibling Rivalry Press (2017)

Purchase @ Sibling Rivalry Press

Review by Travis Chi Wing Lau.

In 1978, Susan Sontag famously argued that “the healthiest way of being ill—is one most purified of, most resistant to, metaphoric thinking.”[1] Yet since the publication of her polemic against the stigmatizing and militaristic language surrounding illness (and later of HIV/AIDS in 1989), scholars have rightly put pressure on this narrow view of metaphor’s capacities. In what ways can metaphors be generative of new ways of being and living with illness and disability? How can metaphors by the ill and disabled reorient and expand our understandings of those experiences and what “health” can be? I come to Kaveh Akbar’s Portrait of the Alcoholic precisely for what it might teach us about addiction’s metaphoric possibilities.

Disability scholarship and activism have long resisted the medical model of disability, which is characterized by a curative impulse to fix or even eliminate disability all together. Underpinning this impulse are assumptions about what constitutes the normal, the natural, and the healthy. Recently, scholars have turned their attention to addiction to consider how it might be imagined beyond the limiting framework of pathology that frames addiction as a state of insatiable lack. I follow this line of thinking to read the Portrait of the Alcoholic as a text that actively resists the curative through a desire to inhabit and reinhabit the seemingly irreconcilable contradictions of alcohol addiction.

Akbar’s collection begins with a prefatory poem, “Some Boys Aren’t Born They Bubble,” which situates the text within what Akbar himself has called a narrative of “recovery”:

some boys aren’t born they bubble

up from the earth’s crust land safely around

kitchen tables green globes of fruit already

in their mouths when they find themselves crying

they stop crying these boys moan

more than other boys they do as desire

demands when they dance their bodies plunge

into space and recover the music stays

in their breastbones they sing songs (11)

As opposed to a straightforward narrative of development and recovery, these boys do not begin ab ovo (“aren’t born”), but rather, they emerge spontaneously into being (“bubble up from the earth’s crust”) rife with “desire.” It is in this state of intense desire that these bodies counterintuitively “recover.” Hardly the stereotypical figure of the addict whose indulgence in the desire to “lick or be licked” is excessive, these boys “sing songs” with the music that they embody; the addict’s pleasure is unexpectedly productive. Even in this opening poem, Akbar begins to modulate an understanding of addictive desire from deviance to effervescent possibility. Addiction is instead a state of imminence that resists a linear time, what Akbar later describes in “Portrait of the Alcoholic Three Weeks Sober” as a “forward [that] seems too chronological” (29).

The temporality of addiction is equally unpredictable and unbound by conventional structures of time: “temptation rarely warns you / a useful model unpredictable as an arrow through the spine / its flightpath its feathery hole who among us hasn’t wished to burst” (30). Akbar’s poems offer us a model of “sick time” that flies in the face of a conventional medical model of diagnosis, treatment, and recovery. Like the boys who “bubble,” addiction is represented through figures in motion rather than through stagnancy – fluctuating states like a flying arrow. As a narrative of addiction, Akbar’s Portrait vulnerably sits with the uncomfortable ambivalence of “being in recovery.” In “Despite Their Size Children Are Easy to Remember They Watch You,” Akbar writes,

to live well is easy a flea leaps and is unshocked by its flight

for others it’s harder and hardly seems worth doing the better a life

the more sadness it leaves… (30)

For Akbar, the assumption that healthiness is necessarily better is a false one. Though he may be on the path toward sobriety, that path is not direct or clear. In fact, the pressure “to live well” can feel “hardly worth doing,” especially when enforced by a medical establishment who is ultimately uninterested in the comparatively “healthy and unremarkable” or those “dying at an average pace” (19). If states of health remain so precarious and relative to individuals, Akbar questions why we fetishize “living well” as central to a eudemonic life worth living. Can addicts “live well”?

By the volume’s conclusion, we are left to reconsider the category of “the alcoholic” all together. Throughout Portrait, Akbar plays with the limitations of language, particularly a language that might rein in the vicissitudes of addiction. “Thinking if I called a wolf a wolf I might dull its fangs,” Akbar suggests the act of naming might contain his temptations (19). Yet language and self-restraint repeatedly fail throughout his poems. I want to suggest that this performative failure leaves open an addictive potential, the risky “and yet and yet” that concludes one of my favorite poems from the collection, “Unburnable the Cold Is Flooding Our Lives.” Akbar reminds us that an addict’s relationship to addiction does not merely cease upon “recovery,” which inherently presumes a fantastical return to some originary state of health. Recovery is a kind of perverse nostalgia, an aching for a homecoming to a home that seems less hospitable and familiar than his addictive pleasures. Appropriately then, Akbar does not leave us with the comfort of resolution because after all “the boat I am building will never be done” (45).

[1] Sontag, Susan. Illness as Metaphor. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1978. 3.

Kaveh Akbar founded and edits Divedapper. His poems appear recently in Poetry, APR, Tin House, PBS NewsHour, Boston Review, and elsewhere. His debut full-length collection, Calling a Wolf a Wolf, will be published in November 2017 by Alice James Books. The recipient of a 2016 Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Fellowship from the Poetry Foundation, Kaveh was born in Tehran, Iran, and currently lives and teaches in Florida.