Quietly Subversive: Revisiting the Life and Work of Gwen John (1876-1939)

by Kristy McGrory

Gwen John

"Young Woman Holding a Black Cat" c.1920–5,

Tate Archive

Gwen John

"Young Woman Holding a Black Cat" c.1920–5,

Tate Archive

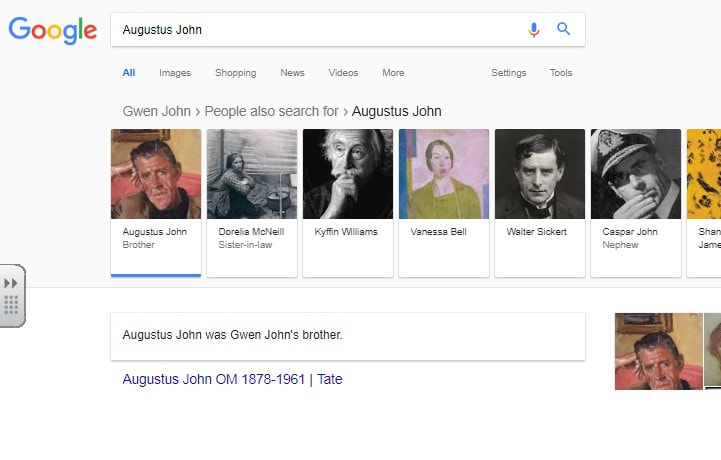

Welsh artist Gwen John was a pioneer of the intimism style of painting that grew out of French impressionism in the early 20th century. While recognition for her formidable talent has grown since her death in 1939, she was woefully underappreciated in her own time, and largely defined by the public in relation to the two key male figures in her life, whose fame and popularity as artists far eclipsed her own: her brother, Augustus John, and her lover, Auguste Rodin.

Gwen John makes a unique contribution to the history of the spinster, as she is inadvertently responsible for the widespread association between single women and cats. The portraits for which she is most famous frequently involve a lone female subject in a domestic setting, often depicted clutching a feline companion. John had several cats herself (some with notably outstanding names like ‘Edgar Quintet’) and, in addition to featuring them in her paintings, John was known to write poetry about them. It was in her poetry that she concretely established the cat as representative of lost romance and absent love.

In her lifetime, Gwen John’s fame was in a large part due to her passionate and unconventional relationship with Rodin, a charismatic womaniser twice her age. Her obsessive and enduring infatuation with him, despite his repeated rejections, raised eyebrows and led to her being remembered by the Telegraph after her death, not for her work, but merely as ‘Rodin’s stalker’.

John’s romantic attachment style in adulthood is undoubtedly the lasting product of the profound childhood trauma she experienced at the hands of her abusive father. Tumultuous relationships and deep melancholy were recurring themes in Gwen John’s personal life. Romantic rejection was something I think she felt very keenly, both when it was happening in reality and also when it wasn’t – a lingering hangover from the lack of love in her formative years. She was, for her entire life, in a state of unrequited love, not just with individual people, but with the world in general, and with her own existence. John’s combination of obsessive dependency on partners, combined with her self-protective tendency towards isolation in later years, suggests to me that she had a deep yearning for something fundamental that no-one in her life was ever really able to give her.

Gwen John "Chloë Boughton-Leigh"

1904–8, Tate Archive

Gwen John "Chloë Boughton-Leigh"

1904–8, Tate Archive

Her paintings, with their subdued colours, modest domestic settings and intimate depictions of subjects, often suggest understatement, quiet acceptance and calm. But they also simultaneously convey a subtle tension under the surface –an almost undetectable sense of restrained desperation. The faces of her portrait subjects can be weary, and occasionally the eyes show flickers of agitation, sometimes even something akin to despair. This is all too fitting for a great artist who was denied appropriate recognition in her lifetime.

John was acutely aware of being underappreciated. She is quoted as stating that she was confident her work was superior to Cezanne’s. The sense of powerlessness and frustration that lingers beneath the placid veneer of her paintings, must, in part, come from this deep sense of injustice. John was resentful the expectation that, as a woman, her primary ambition should be to marry and have children. John was, in fact, vocally indignant on this point, saying: “I think if we are to do beautiful pictures, we ought to be free from family conventions and ties.”

The one constant in Gwen John’s life was the support of her brother, Augustus. While he enjoyed fame and his gender afforded him the freedom to enjoy a spectacularly decadent ‘Bachelor’-type lifestyle (he drank far too much and is rumoured to have fathered up to 100 illegitimate children), Augustus was consistently outspoken about his sister’s superior talent. He famously asserted that he would be remembered by future generations solely as the brother of Gwen John. No disrespect to the man, an accomplished artist and very compelling and interesting character in his own right, but given the gross unfairness of the relative status of the siblings in their heyday, the accuracy of his prediction is somewhat satisfying:

John was acutely aware of being underappreciated. She is quoted as stating that she was confident her work was superior to Cezanne’s. The sense of powerlessness and frustration that lingers beneath the placid veneer of her paintings, must, in part, come from this deep sense of injustice. John was resentful the expectation that, as a woman, her primary ambition should be to marry and have children. John was, in fact, vocally indignant on this point, saying: “I think if we are to do beautiful pictures, we ought to be free from family conventions and ties.”

The one constant in Gwen John’s life was the support of her brother, Augustus. While he enjoyed fame and his gender afforded him the freedom to enjoy a spectacularly decadent ‘Bachelor’-type lifestyle (he drank far too much and is rumoured to have fathered up to 100 illegitimate children), Augustus was consistently outspoken about his sister’s superior talent. He famously asserted that he would be remembered by future generations solely as the brother of Gwen John. No disrespect to the man, an accomplished artist and very compelling and interesting character in his own right, but given the gross unfairness of the relative status of the siblings in their heyday, the accuracy of his prediction is somewhat satisfying:

Kirsty McGrory is a teacher and writer from Edinburgh, Scotland. She graduated from the University of Edinburgh with an MA (Hons) in English Literature in 2008. She teaches Secondary English and Media, and spends her spare time writing articles and reviews of films, comedy and visual art.