Raven King by Fox Henry Frazier

Review by Samantha Duncan.

From violence and trauma form kinship, magic, and strength in Fox Henry Frazier’s Raven King, a poetry collection from Yes Poetry rooted in mythology and crime that plants one foot in mysticism and the other starkly in reality.

Frazier shows what it’s like to process and reflect on trauma, both through an internal and external lens. Shows how an assault, for example, intimately changes a victim as it also aligns with stories we hear of other victims – high profile, local, historical. There is a definite sense throughout Raven King that everything is connected, through stars, patriarchy, and victimhood.

This collection confronts readers with a landscape where assault and violence against women feels like a given, where victims are hidden in basements and backyards and those left to read and bear witness to these stories must conjure the strength to navigate a world in which they, or their daughters, could be next. It’s a landscape that exists worldwide, in the past and present, in the real and in the mythical, because men’s desire to control women is just that pervasive. Aptly titled is the poem, “Everywhere in the World, They Hurt Little Girls,” about a girl who was murdered while working a paper route to save money to throw her pregnant teacher a baby shower:

“…I believe that we are

made of gossamer, crystalline, infinite, shimmering

material inside ourselves and things our bodies do.

but also, I don’t want to say he killed her because it’s obscene

to announce that he did it, that men like James do

exactly what they want in this world, make the horror stick. Sick”

Girls killed as more girls are brought into the world, the cycle promises continuance, always moving. The poem shifts to the narrator raising a baby and experiencing California wildfires, seeing beauty through hopelessness, struggling and despairing but surviving through it all:

“…The sky is still paradise

blue over one side of the house.

I don’t believe that things will get better.”

Rather than the packaged “true crime” style of storytelling we’re used to seeing about the rapes and murders of countless women, Frazier inserts readers into the journey of the survivor, women who did escape their abusers, only to be faced daily with news of women who didn’t and the prospect that it could have been them, that it still could be them or the daughters born to them.

This narrative of pervasive violence manifests abundance elsewhere throughout Raven King. Long titles set up many of the poems, lengthy headlines informing readers who is observing (often The Fox-Haired Seer or The Raven-Haired Cartographers’ Daughter) and what murder story is being consumed. Several poems titled “Letter To Diane Arbus,” utilize the page by creating white space, while the poems themselves channel the intensity of Arbus’s photographs (“thought he’d found his sweet pink / mitten of eternity in me”). These titles are intentionally repetitive, mirroring the systemic promise of never-ending trauma.

The collection culminates in an expansive essay titled “I Live In the Shadow Hills", whose tapestry takes readers through domestic abuse, cult leaders, and the occult, with Nine Inch Nails as its soundtrack and the Los Angeles wildfires as its backdrop. Photos and police reports document the exhaustive efforts it often takes to escape and survive an abusive relationship, a reminder of the difficulties of following well-meaning but ignorant advice to just leave. As the world around Frazier literally burns and electricity around her behaves in mysterious ways, she becomes pregnant with a daughter and it becomes clear what future is really at stake when escaping violent men.

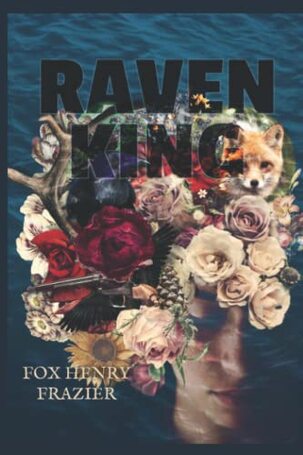

Abundance is felt throughout Raven King as a multimedia work, from its accompanying illustrations to its soundtrack. Joanna C. Valente’s mixed media illustrations nod at each poem, testifying for both victims and survivors. Blood Honey’s debut album serves as an accompaniment to the collection, promising to “bring the listener under the wing of the Raven King.” Another shout-out goes to Jen Stein Hauptman for the book’s gorgeous cover, a digital collage of a head of never-ending flowers, barely concealing a gun. Raven King is not just a book, but a multi-modal world of history, spirituality, strength, survival, and remembrance.

From violence and trauma form kinship, magic, and strength in Fox Henry Frazier’s Raven King, a poetry collection from Yes Poetry rooted in mythology and crime that plants one foot in mysticism and the other starkly in reality.

Frazier shows what it’s like to process and reflect on trauma, both through an internal and external lens. Shows how an assault, for example, intimately changes a victim as it also aligns with stories we hear of other victims – high profile, local, historical. There is a definite sense throughout Raven King that everything is connected, through stars, patriarchy, and victimhood.

This collection confronts readers with a landscape where assault and violence against women feels like a given, where victims are hidden in basements and backyards and those left to read and bear witness to these stories must conjure the strength to navigate a world in which they, or their daughters, could be next. It’s a landscape that exists worldwide, in the past and present, in the real and in the mythical, because men’s desire to control women is just that pervasive. Aptly titled is the poem, “Everywhere in the World, They Hurt Little Girls,” about a girl who was murdered while working a paper route to save money to throw her pregnant teacher a baby shower:

“…I believe that we are

made of gossamer, crystalline, infinite, shimmering

material inside ourselves and things our bodies do.

but also, I don’t want to say he killed her because it’s obscene

to announce that he did it, that men like James do

exactly what they want in this world, make the horror stick. Sick”

Girls killed as more girls are brought into the world, the cycle promises continuance, always moving. The poem shifts to the narrator raising a baby and experiencing California wildfires, seeing beauty through hopelessness, struggling and despairing but surviving through it all:

“…The sky is still paradise

blue over one side of the house.

I don’t believe that things will get better.”

Rather than the packaged “true crime” style of storytelling we’re used to seeing about the rapes and murders of countless women, Frazier inserts readers into the journey of the survivor, women who did escape their abusers, only to be faced daily with news of women who didn’t and the prospect that it could have been them, that it still could be them or the daughters born to them.

This narrative of pervasive violence manifests abundance elsewhere throughout Raven King. Long titles set up many of the poems, lengthy headlines informing readers who is observing (often The Fox-Haired Seer or The Raven-Haired Cartographers’ Daughter) and what murder story is being consumed. Several poems titled “Letter To Diane Arbus,” utilize the page by creating white space, while the poems themselves channel the intensity of Arbus’s photographs (“thought he’d found his sweet pink / mitten of eternity in me”). These titles are intentionally repetitive, mirroring the systemic promise of never-ending trauma.

The collection culminates in an expansive essay titled “I Live In the Shadow Hills", whose tapestry takes readers through domestic abuse, cult leaders, and the occult, with Nine Inch Nails as its soundtrack and the Los Angeles wildfires as its backdrop. Photos and police reports document the exhaustive efforts it often takes to escape and survive an abusive relationship, a reminder of the difficulties of following well-meaning but ignorant advice to just leave. As the world around Frazier literally burns and electricity around her behaves in mysterious ways, she becomes pregnant with a daughter and it becomes clear what future is really at stake when escaping violent men.

Abundance is felt throughout Raven King as a multimedia work, from its accompanying illustrations to its soundtrack. Joanna C. Valente’s mixed media illustrations nod at each poem, testifying for both victims and survivors. Blood Honey’s debut album serves as an accompaniment to the collection, promising to “bring the listener under the wing of the Raven King.” Another shout-out goes to Jen Stein Hauptman for the book’s gorgeous cover, a digital collage of a head of never-ending flowers, barely concealing a gun. Raven King is not just a book, but a multi-modal world of history, spirituality, strength, survival, and remembrance.

Samantha Duncan is the author of four poetry chapbooks, including Playing One on TV (Hyacinth Girl Press, 2018) and The Birth Creatures (Agape Editions, 2016), and her work has recently appeared in BOAAT, SWWIM, Kissing Dynamite, Meridian, and The Pinch. She lives in Houston.