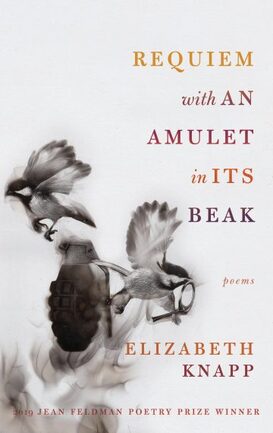

Requiem with an Amulet in Its Beak by Elizabeth Knapp

Paperback: 82 pages

Publisher: Washington Writers’ Publishing House (Jean Feldman Poetry Prize Winner) October 15, 2019

Purchase: @ Amazon

Review by Jennifer Martelli.

As I read Elizabeth Knapp’s award-winning collection, Requiem with an Amulet in Its Beak, I was reminded of a statement by Temple Grandin, a professor of animal science and autism spokesperson. Describing her life experience, she states, “Much of the time, I feel like an anthropologist on Mars.” The poems in Knapp’s collection speak to this otherness while navigating the beautiful, broken landscape of the United States. In her poem, “Capital I,” Knapp writes:

I’ve been abducted by aliens

and brainwashed into believing

that there is no actual self to protect.

Utilizing pop icons—David Bowie, Linda Rondstadt, Tom Cruise, Robin Williams, Kurt Cobain—Knapp creates a meta collection, describing the process of giving voice and sensibility to this acute separateness. Knapp links the self to the American landscape by joining two of our most famous outsiders, Kurt Cobain and Emily Dickinson. In “Self-Portrait as the Love Child of Kurt Cobain and Emily Dickinson,” she writes

Naturally, I’m an introvert of the

most introverted sort. I keep versions of myself under glass when I can oc-

casionally do experiments on them, as the mood strikes.

. . . . I won’t say I miss them, though

sometimes when the wind blows through me,

I can almost hear them sing.

I love how Knapp entwines and embraces these current icons with classical references. Like an anthropologist, Knapp creates a narrative reaching into the past as a way of defining the present. The meta poem written in reference to the outsider and the self-injurious, becomes both structural and thematic. In one of her meta Kurt Cobain poems which are laced throughout the book, Knapp balances King Lear (exile) and Kurt Cobain (self-proclaimed outsider) in “Self-Portrait as Kurt Cobain’s Childhood Wound” by her choice of placement:

gaping hole of his left eye socket or the brain matter

scattered like jewels across the floor

(Bless their sweet eyes, they bleed.) The thing is, I think

Kurt’s fatal wound and his childhood wound

were one and the same.

This United States Knapp is trying to define is a land of outsiders, or hurt people, and at times, self-indulgent ones. In her poem “The Martian,” the alien states: “I became the only other, / I know. Take this selfie.” It is a country of cruelties as well. In the heart-breaking elegy, “Koko the Gorilla is Dead,” Knapp deftly addresses the other by lacing Koko, Robin Williams, and the migrant:

I wanted to write an elegy for the gorilla

who famously learned signed language

from a researcher who believed that apes

had something to teach us about being

human . . . .

That summer, migrant children cried

at the barbed wire border, while in a hotel

in Strasbourg, everyone’s favorite drifter

hanged himself with a belt.

Knapp’s poems, by grappling with the other, embrace the dead as the ultimate outsider. These poems, then, also confront faith and belief. I fell in love with Knapp’s poem “Faith,” which recalls the late singer, “The way George Michael sang it, / even I, apostate, believed.” Once again, Knapp references the not-too-distant past:

if you

were a teenaged girl growing up

in the 80s, you fell too . . . .

Still,

sometimes when the body hears

the memory of music, it’s holy.

The unliving—whether dead or never-born—are ever-present. In “Poem in the Manner of the Year in Which I Was Born,” Knapp’s words become a child—or perhaps the past becomes the child when the speaker states:

You never heard a word

about the IRA bombing, nor did the Texas Chainsaw

Massacre terrorize you . . . .

I want to swaddle you in yesterday’s headlines

and send you back down the river, no wiser

than the day you came blaring into the world.

The sociologist/photographer Jean Baudrillard confronts and counters these questions of self. In “My Brain is Mad for Baudrillard,” Knapp writes,

Some blame

the rise of right-wing populism

on post-modern windbags like you.

He is a perfect companion of Cindy Sherman, photographer and self-portraitist. In her poem, “Self-Portrait as Cindy Sherman’s Instagram Account,” Knapp states, “The self is projected / against a million anonymous eyes.” Here is our USA: angry and self-indulgent. In her mega meta poem, “Recurring Dream: Elevator (Co-Starring Prince and with an Unscripted Appearance by Emily Dickinson),” Knapp becomes a Cecil B. DeMille, creating an opus-like hydra of a poem. Knapp writes, “Dearly beloved, never try to decode a dream / through the lens of a poem.” In a moving box, Knapp encompasses history, modern-poetic thought, and pop culture:

There are better poets

to draw on for these things—Berryman,

for example, Franz Wright, most definitely--

and besides, as is well known, elevators

do not commonly appear in American poetry

until the early part of the twentieth century.

Requiem with An Amulet in Its Beak is a chronicle of our nation. It is a muscular, funny, sad, and fully-American collection. This violent and fraught landscape is ours, it’s where we live and contemplate our own existence, while “one roving eye stares back.” Knapp’s unflinching examination of this country and all of its brilliant, tragic ghosts is mired in an ancient, poetic sense. Conjuring Orpheus in “Self-Portrait as Kurt Cobain’s Left-Handed Guitar,” Knapp reminds us all that we’re all struggling “to render the longing of the object in a way that is human and inhuman, inevitable . . . . what matters is the playing.”

Elizabeth Knapp grew up in Houston and has lived in Massachusetts, California, Michigan, and Maryland, with brief stints in London and Prague. She earned a BA from Amherst College, an MFA from the Bennington Writing Seminars, and a PhD from Western Michigan University. Her first book of poems, The Spite House, won the 2010 De Novo Poetry Prize and was published by C&R Press in 2011. Her second collection, Requiem with an Amulet in Its Beak, won the 2019 Jean Feldman Poetry Prize and was published by the Washington Writers’ Publishing House in 2019. Her other honors include the 2018 Robert H. Winner Memorial Award from the Poetry Society of America, a 2017 Maryland State Arts Council Individual Artist Award, and the 2015 Literal Latté Poetry Award. Her poems have appeared in many journals and anthologies, including Best New Poets, Kenyon Review, The Massachusetts Review, North American Review, and Quarterly West. An associate professor of English at Hood College, she lives in Frederick, Maryland with her husband, the novelist Robert Eversz, and their two children.