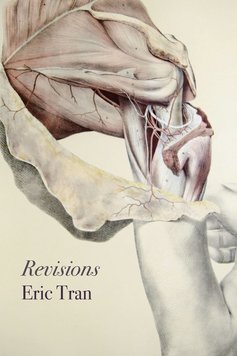

Revisions by Eric Tran

Paperback: 50 pgs

Publisher: Sibling Rivalry Press (2018)

Purchase @ Sibling Rivalry Press

Review by Travis Chi Wing Lau.

As Ocean Vuong reminds us, Eric Tran’s Revisions invokes a long tradition of “healer-wordsmiths” like William Carlos Williams (The Doctor Stories) and Rafael Campo (What the Body Told). The figure of the poet-doctor has been central to the historical development of early American medicine. In this period prior to the formal professionalization of medicine within medical schools, humanistic methods of knowledge-making and expression coexisted with scientific and medical empiricism. Physicians like S. Weir Mitchell and Benjamin Rush widely deployed metaphor and other forms of figurative language for how they provided experimental space for the testing and revision of medical theories. The imagination and the literary were themselves practices of medicine.1 The publication of the Carnegie Foundation’s 1910 report on the state of medical education in the U.S. and Canada (commonly referred to as the Flexner Report) set into motion institutional reforms that would make medical instruction more scientific (coursework in chemistry, biology, physics alongside laboratory and clinical practica) instead of humanistic (Latin, Greek, or philosophy). Representing a generation of poet-doctors boldly resisting the cultural amnesia of this older model of medical training that is no less rigorous, no less necessary for the work of healing, Tran writes intimately from within and without the medical establishment. It is the tense and tender negotiation between these positions that define his body of work.

Throughout Revisions, Tran meditates upon scenes of medical pedagogy. In “Socratic Method,” the speaker ventriloquizes the rote way in which a medical student is taught the proper terms for conditions and parts of the body. The irony is that the method represented is hardly Socratic; rather, it reads like a set of imperatives for what the student must learn to “say” on the job. Instead of a true elenchus method, which encourages critical thinking by having students engage in interrogative dialogue with one another and with the instructor, there are only performative rehearsals for what the clinician should ultimately say or do. Tran highlights the perverse disconnect between what it is to “say wheezes, say breath sounds, say sectioned and quartered” in the face of “your patient’s sobbing mother.” Medical education’s hypervalorization of self-control, procedure, and preparedness betrays its own limits for dealing with the personal, the human. What begins as jargon (“fascia,” “statin,” “sterile,” “CT”) dissolves into the colloquial “sucker punch,” “sundown and Posey.” The coexistence of these two disparate affective registers characterizes the reality of medical labor, which persistently demands the clinician to navigate between them.

“Forensics Lecture After the Shooting of Michael Brown” echoes this affective disconnect, as the speaker grapples with the tragic failure of “medicine [that] can’t always undo the violence.” The lecturer scrolling through slides of “wounds to commit to memory” and images of “a wrist flayed open to the bone” clashes against the stark brutality of police violence, for which the lecturer has “no slides / about closing split scalps, for helping skin pull itself / whole.” Medicine is again framed in terms of its inadequacy, for it cannot begin to mend the physical and psychic damage of a long legacy of violent racism: “No cure for tear gas, for Tasers, for another black boy / gunned down by cops.” What medicine reduces to “a physics equation” depersonalizes the trauma to the level of an individual body uncomplicated by narrative, by racial history. Medicine works by deindividualizing but at the risk of missing the point entirely: the lecturer’s “no story, / no resolution” betrays how racial trauma is something institutional, structural in which medicine itself has and remains complicit. Only the tragedy of violence, of “blood-letting, inside bursting out,” can make clear what the stakes are of what continues to “go last” in our culture: “always a mother without her son.” The most difficult aspect of practicing medicine is ethically bearing witness to what is often unbearable, irrevocable loss, for which there is no cure.

Tran’s later poem, “The First X-Ray,” reminds us again that the history of medicine is a violent one: “Biotech is built small / for warzones, to trace poison in water. Mustard gas / fathered chemo: autopsies of blistered victims / showed tumors lulled into slumber.” Michel Foucault has noted how Western medicine’s development of diagnosis worked to reduce bodies to sets of symptoms that manifest in organs and organ systems.2 The “medical gaze,” which claims the ability and the right to peer into bodies in order to unveil their secrets, dehumanizes by discarding the patient’s identity and narrative of self in favor of a narrative composed of laboratory test results and diagnostic taxonomies. This “gaze” is only further enhanced by the rise of medical imaging technologies like the x-ray and ultrasound. Tran writes from both the subject position of a clinician training to wield the “medical gaze” and of a queer person of color disproportionately subjected to the scrutiny of that “gaze.” “Anatomy & Phys” documents the speaker’s processing the suicide of one of his teachers, Dr. Garza, later revealed to have raped his students. Rather than a reductive moralizing of Dr. Garza’s “picking” of students from his own classes, the speaker expresses an unexpected kinship with him: “imagine / Garza and I were similar that way.” Garza and the speaker connect over the mutual experience of marginality, of queer survival in the space of the clinic—an experience implied to have precipitated Garza’s suicide. Alongside an intellectual and professional formation as a clinician is an erotic formation that must happen elsewhere, that sometimes dare not speak its own name.

1See Sari Altschuler’s The Medical Imagination: Literature and Health in the Early United States (UPenn Press 2018) for a superb historical account of the privileged place of imagination and the humanities in late-eighteenth and nineteenth-century American medicine.

2See Michel Foucault’s Naissance de la Clinique (The Birth of the Clinic) (Presses Universitaires de France 1963, Pantheon 1973).

Eric Tran is a medical student at the University of North Carolina and holds an MFA from UNCW. He is the author of Affairs with Men in Suits, and was winner of the 2015 New Delta Review Matt Clark Prose Award and a finalist in the 2015 Indiana Review 1/2K Prize and the Tinderbox Poetry Prize.