Interview with Sarah Ghazal Ali

Up the Staircase Quarterly: Hello, Sarah! Thanks for joining me for this interview. I would like to start by discussing your debut full length poetry collection, Theophanies (January 2024), which was selected as the 2022 Editors’ Choice for the Alice James Award.

You begin Theophanies with a quotation from poet Edmond Jabès: “I gave you my name, Sarah. And it is a dead end road.” How did you first encounter this quote, and how does it inform your collection? How did you come about choosing a direction or angle for your manuscript?

Sarah Ghazal Ali: There’s a Persian tradition known as fal-e-Hafez, in which you open to a page of Hafez’s dīvan at random and extract from that page— from the first verses your eyes fall upon—some divine, poetic wisdom. I love this practice of bibliomancy, and like to approach most poetry collections that I read this way. I open new books to the middle to receive their wisdom, some sort of guiding framework that might inform how to read the book as a whole. It’s not always successful, but it definitely was when I first read Jabès’ “The Book of Questions” a few years back. The language throughout is feverish, leaping. It has that aphoristic Hafez quality, that earnestly prophetic quality, and I knew, upon my first reading, that something essential was words away from reaching me. The moment I read the line about the character Sarah receiving her name, I knew it would inform every poem I’d write onwards. More than anything else, I have repeated this line to myself throughout the writing of the poems that would make up Theophanies, which is a book obsessed with naming.

I believe in naming into presence what otherwise remains obscured or exiled, and find this epigraph to be a provocative entry point. Before you even begin the book, you are warned: Sarah is a dead end road. And if that is true, what does it mean for the named speakers in the book, or for the actual name that I inhabit and carry in the world? What does it mean that God changed her name from Sarai to Sarah? I didn’t choose my name, and I didn’t choose a direction or angle for this book. Each poem offered something, and named something, and I just tried my best to receive it. Putting together this manuscript, and finding Theophanies poem by poem, felt like bibliomancy, too. It was a process of deep faith in the dark.

UtSQ: Theophanies includes a variety of stylized forms: litany, elegy, epistle, among others. I was particularly drawn towards your ghazals, which were woven beautifully throughout the manuscript. In an interview with Hayden’s Ferry Review, you said of the ghazal, “I find it to be a form of inexhaustible depths.” As you were piecing together this manuscript, how did you decide which styles and/or formats to utilize to convey your own depths? How did the concept or theme of your work evolve with these decisions?

SGA: I appreciate this question, because I am really challenged by form, both on and off the page. We experience the world first through form, through the physical form of our bodies. Sense and sense-making is linked to the physical, and because of that, I tend to marry form and content in my poems. Certain forms emerged organically with certain poems. Sometimes, I had the idea for the body of a poem long before the language came to me, as was the case for the family tree / contrapuntal-esque poem “Matrilineage [Recovered].” Contrapuntals were particularly useful conduits for my thinking. I tried to resist the lure of the autobiographical speaker, the single, confessional voice—I wanted (and still want) for this book to be read as polyphonic. Contrapuntals and persona poems allowed me to braid in multiple voices, women, readings, interpretations. Ghazals allowed me to bring in one facet of an “I” while still remaining faithful to each’s central subject and questions. The pantoum “Mother of Nations” could only be a pantoum, could only exist in such a cyclical, repetitive form. It isn’t true, so to speak, separate from its form. I think one project of the book is to probe the bounds of supplication and beseeching—how many different forms and styles of speaking will help lift my language to the divine, or to the women of sacred history I am endlessly imploring?

UtSQ: From a craft standpoint, did you face a challenge with a particular poem in this collection? Which piece came “easiest” to the page?

SGA: I really struggled with the ghazals, and am surprised that they are what readers have been responding to the most. I hold ghazals to an impossible standard, and every ghazal I’ve ever written has felt like a tremendous personal failure. I think all the ghazals in Theophanies are failures, but have included them as a record of my striving toward.

The poem that came with ease was “Sarai” —I just woke up one morning and had Sarai on my mind, the version of Sarah before God changed her name. The poem appeared in a matter of minutes. Each line emerged simply and quickly, and I didn’t touch the poem again afterward.

UtSQ: While navigating the complexities of your subject matter, what idea or feeling were you hoping readers would take away from this collection? What did you personally take away from the experience of writing and publishing these poems?

SGA: I was bewildered while writing these poems, and every poem that didn’t make it into the book. I struggle to consider them from a distance, to speak coherently about them. I think all I can ask is that readers approach these poems with a willingness to wonder, and without automatically applying a Bibilical framework to their reading. There is more than one Abrahamic faith, and so more than one account of every shared story. There is more to reading than ascribing or searching for certainty —I hope readers will be bewildered alongside me!

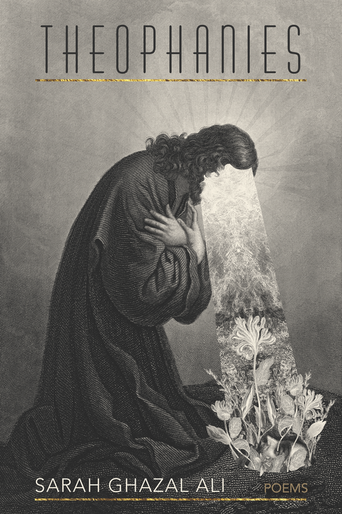

UtSQ: I would love to know more about the striking cover art of Theophanies. Can you tell us about the artist, the idea behind the work, and how it was selected as the cover?

SGA: I first came across this image, titled “Ground,” by the remarkable artist Dan Hillier back in 2020, and knew immediately that it -was- Theophanies. It’s based on the 17th century painting “Christ’s Agony in the Garden of Gethsemane” by Italian painter Carlo Dolci. I knew I wanted this to be the cover long before the book was even completed, and lost so much sleep while my press contacted Mr. Hillier to get his permission to use the art! A theophany by definition is an encounter with God in some physical, manifest form. This image of a faceless figure, presumably Jesus, in such a dynamic exchange with the earth felt like the embodiment of a theophany. When I try to imagine how it must have felt for God to talk to Sarah and Mary through angels, “Ground” comes to mind. To “see” the divine in some way must be to lose your own image in what is shown to you.

UtSQ: Writing a book can be an intense process. Was there a particular piece of media or a medium that you can remember consuming while writing Theophanies; perhaps a book, album, or film that might have brought some relief or maybe even inadvertently aided you?

SGA: I read a lot of scripture, and returned to the stories of Abraham obsessively. Abraham, Sarah, and Hajar haunt me still, long after the book has been finished, so to speak. I returned to these paintings by Richard McBee constantly as well. Mary Szybist’s poetry was, and still is, a balm, a blessing. Incarnadine made Theophanies possible. Mary’s work encouraged me to lean into doubt, and to fall deeper into my obsession with my namesake.

UtSQ: Let’s shift gears a little. Tell us about your first significant literary encounter. How did this experience inspire you, or shape you, into the writer you have become?

SGA: In elementary school, I remember having my mind blown wide open when I read Naomi Shihab Nye’s novel Habibi. I was exposed to some diverse literature as a kid in the late 90’s, but never anything with Arabs, South Asians, or Muslims. Reading Habibi I recognized some part of myself on the page, and in the main character Liyana. It was the first time I stopped and thought, wait, I get to be in books, too? Books can take place in places like Palestine? And I’m not Palestinian! I’m Pakistani, but that book offered the closest thing to a mirror I’d encountered at such a young age. Representation is a project fraught with failure and limitations, and it’s one I am wary of glorifying or aligning myself with, but I will say that reading about Liyana and her family’s move to the West Bank helped me better conceptualize my own humanity. That initial exposure to Naomi Shihab Nye was what made me want to be a Writer, capital W. Reading Habibi brought wonder into my reading life, and gave me a nudge to imagine myself as I am—South Asian, and Muslim, and a girl, and entirely worth writing about.

UtSQ: Finally, Sarah, if you could have a meal with anyone, dead or alive, real or imaginary, who would it be, and what on earth would the two of you eat?

SGA: I would love to have a meal with Etel Adnan, may she rest in peace. I imagine we would meet by the sea in Sausalito, and eat savory pastries, and look up at the mountain in between bites.

You begin Theophanies with a quotation from poet Edmond Jabès: “I gave you my name, Sarah. And it is a dead end road.” How did you first encounter this quote, and how does it inform your collection? How did you come about choosing a direction or angle for your manuscript?

Sarah Ghazal Ali: There’s a Persian tradition known as fal-e-Hafez, in which you open to a page of Hafez’s dīvan at random and extract from that page— from the first verses your eyes fall upon—some divine, poetic wisdom. I love this practice of bibliomancy, and like to approach most poetry collections that I read this way. I open new books to the middle to receive their wisdom, some sort of guiding framework that might inform how to read the book as a whole. It’s not always successful, but it definitely was when I first read Jabès’ “The Book of Questions” a few years back. The language throughout is feverish, leaping. It has that aphoristic Hafez quality, that earnestly prophetic quality, and I knew, upon my first reading, that something essential was words away from reaching me. The moment I read the line about the character Sarah receiving her name, I knew it would inform every poem I’d write onwards. More than anything else, I have repeated this line to myself throughout the writing of the poems that would make up Theophanies, which is a book obsessed with naming.

I believe in naming into presence what otherwise remains obscured or exiled, and find this epigraph to be a provocative entry point. Before you even begin the book, you are warned: Sarah is a dead end road. And if that is true, what does it mean for the named speakers in the book, or for the actual name that I inhabit and carry in the world? What does it mean that God changed her name from Sarai to Sarah? I didn’t choose my name, and I didn’t choose a direction or angle for this book. Each poem offered something, and named something, and I just tried my best to receive it. Putting together this manuscript, and finding Theophanies poem by poem, felt like bibliomancy, too. It was a process of deep faith in the dark.

UtSQ: Theophanies includes a variety of stylized forms: litany, elegy, epistle, among others. I was particularly drawn towards your ghazals, which were woven beautifully throughout the manuscript. In an interview with Hayden’s Ferry Review, you said of the ghazal, “I find it to be a form of inexhaustible depths.” As you were piecing together this manuscript, how did you decide which styles and/or formats to utilize to convey your own depths? How did the concept or theme of your work evolve with these decisions?

SGA: I appreciate this question, because I am really challenged by form, both on and off the page. We experience the world first through form, through the physical form of our bodies. Sense and sense-making is linked to the physical, and because of that, I tend to marry form and content in my poems. Certain forms emerged organically with certain poems. Sometimes, I had the idea for the body of a poem long before the language came to me, as was the case for the family tree / contrapuntal-esque poem “Matrilineage [Recovered].” Contrapuntals were particularly useful conduits for my thinking. I tried to resist the lure of the autobiographical speaker, the single, confessional voice—I wanted (and still want) for this book to be read as polyphonic. Contrapuntals and persona poems allowed me to braid in multiple voices, women, readings, interpretations. Ghazals allowed me to bring in one facet of an “I” while still remaining faithful to each’s central subject and questions. The pantoum “Mother of Nations” could only be a pantoum, could only exist in such a cyclical, repetitive form. It isn’t true, so to speak, separate from its form. I think one project of the book is to probe the bounds of supplication and beseeching—how many different forms and styles of speaking will help lift my language to the divine, or to the women of sacred history I am endlessly imploring?

UtSQ: From a craft standpoint, did you face a challenge with a particular poem in this collection? Which piece came “easiest” to the page?

SGA: I really struggled with the ghazals, and am surprised that they are what readers have been responding to the most. I hold ghazals to an impossible standard, and every ghazal I’ve ever written has felt like a tremendous personal failure. I think all the ghazals in Theophanies are failures, but have included them as a record of my striving toward.

The poem that came with ease was “Sarai” —I just woke up one morning and had Sarai on my mind, the version of Sarah before God changed her name. The poem appeared in a matter of minutes. Each line emerged simply and quickly, and I didn’t touch the poem again afterward.

UtSQ: While navigating the complexities of your subject matter, what idea or feeling were you hoping readers would take away from this collection? What did you personally take away from the experience of writing and publishing these poems?

SGA: I was bewildered while writing these poems, and every poem that didn’t make it into the book. I struggle to consider them from a distance, to speak coherently about them. I think all I can ask is that readers approach these poems with a willingness to wonder, and without automatically applying a Bibilical framework to their reading. There is more than one Abrahamic faith, and so more than one account of every shared story. There is more to reading than ascribing or searching for certainty —I hope readers will be bewildered alongside me!

UtSQ: I would love to know more about the striking cover art of Theophanies. Can you tell us about the artist, the idea behind the work, and how it was selected as the cover?

SGA: I first came across this image, titled “Ground,” by the remarkable artist Dan Hillier back in 2020, and knew immediately that it -was- Theophanies. It’s based on the 17th century painting “Christ’s Agony in the Garden of Gethsemane” by Italian painter Carlo Dolci. I knew I wanted this to be the cover long before the book was even completed, and lost so much sleep while my press contacted Mr. Hillier to get his permission to use the art! A theophany by definition is an encounter with God in some physical, manifest form. This image of a faceless figure, presumably Jesus, in such a dynamic exchange with the earth felt like the embodiment of a theophany. When I try to imagine how it must have felt for God to talk to Sarah and Mary through angels, “Ground” comes to mind. To “see” the divine in some way must be to lose your own image in what is shown to you.

UtSQ: Writing a book can be an intense process. Was there a particular piece of media or a medium that you can remember consuming while writing Theophanies; perhaps a book, album, or film that might have brought some relief or maybe even inadvertently aided you?

SGA: I read a lot of scripture, and returned to the stories of Abraham obsessively. Abraham, Sarah, and Hajar haunt me still, long after the book has been finished, so to speak. I returned to these paintings by Richard McBee constantly as well. Mary Szybist’s poetry was, and still is, a balm, a blessing. Incarnadine made Theophanies possible. Mary’s work encouraged me to lean into doubt, and to fall deeper into my obsession with my namesake.

UtSQ: Let’s shift gears a little. Tell us about your first significant literary encounter. How did this experience inspire you, or shape you, into the writer you have become?

SGA: In elementary school, I remember having my mind blown wide open when I read Naomi Shihab Nye’s novel Habibi. I was exposed to some diverse literature as a kid in the late 90’s, but never anything with Arabs, South Asians, or Muslims. Reading Habibi I recognized some part of myself on the page, and in the main character Liyana. It was the first time I stopped and thought, wait, I get to be in books, too? Books can take place in places like Palestine? And I’m not Palestinian! I’m Pakistani, but that book offered the closest thing to a mirror I’d encountered at such a young age. Representation is a project fraught with failure and limitations, and it’s one I am wary of glorifying or aligning myself with, but I will say that reading about Liyana and her family’s move to the West Bank helped me better conceptualize my own humanity. That initial exposure to Naomi Shihab Nye was what made me want to be a Writer, capital W. Reading Habibi brought wonder into my reading life, and gave me a nudge to imagine myself as I am—South Asian, and Muslim, and a girl, and entirely worth writing about.

UtSQ: Finally, Sarah, if you could have a meal with anyone, dead or alive, real or imaginary, who would it be, and what on earth would the two of you eat?

SGA: I would love to have a meal with Etel Adnan, may she rest in peace. I imagine we would meet by the sea in Sausalito, and eat savory pastries, and look up at the mountain in between bites.

Sarah Ghazal Ali is the author of THEOPHANIES, selected as the Editors' Choice for the 2022 Alice James Award, and forthcoming with Alice James Books in January 2024.

A 2022 Djanikian Scholar and winner of the Sewanee Review Poetry Prize, her poems appear in POETRY, American Poetry Review, Pleiades, The Yale Review, Guernica, and elsewhere.

A former Stadler Fellow at Bucknell University, Sarah is the editor for Palette Poetry and poetry editor for West Branch. She holds an MFA in poetry from the University of Massachusetts Amherst.