Laura Madeline Wiseman reviews Scorched Altar: Selected Poems & Stories 2007-2014

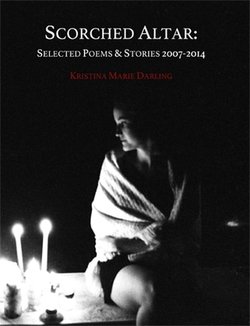

Scorched Altar by Kristina Marie Darling

Paperback: 178 pages

Publisher: BlazeVOX Books (2015)

Purchase: Available at BlazeVOX

“She wanted to understand the innermost workings of this elaborate machine”: Scorched Altar Review by Laura Madeline Wiseman

Rich with sensory details and scene, Kristina Marie Darling’s new book Scorched Altar collects work from twelve previous collections and invites readers to fragment their expectations of book structure, much as she fragments the structure of her sentences. She writes, “My cold blue lips” (134), “Fallen branches. A dead hummingbird” (124), “An uncanny brightness in every window” (105), and “The door to the gallery groaning on its hinges” (27). Indeed, Darling is positing a metaphorical loss and death of the book by opening it, an opening that suggests books are stuck in one manner of delivery. To accomplish this, Darling’s explores a book’s structural devices such as glossaries, diction and tone, notes and footnotes, time’s function within storytelling, and the theme of love and affection.

Darling troubles the stability of language by defining terms within a glossary. In “A History of Melancholia: Glossary of Terms” from The Body is a Little Gilded Cage, Darling defines a set of terms (e.g. locket, memento, nightingale) that are dependent on the text, rather than dependent on the dictionary, or a larger cultural context, positioning the reader of her text as not native to the English language, contemporary culture, or the romantic world within the story. She writes, “nightingale A harbinger of both despair and onslaught of winter. Its bright mornings and colorless evenings” (55). Darling explores themes of courtship and objects of affections, as well as the metaphor of wedded woman as caged bird within the poem, but from the position of outsider.

Darling also explores the use of tone and diction within books. The poem “Palimpsest” from Compendium gives shifts in diction, literary criticism, description, and story. In the second “Chapter One” description, she writes, “His appearance may be read as a culmination of several recurring motifs” (27), taking up the linguistic phrasing of scholarship. Likewise in the selection from Palimpsest, the “Chapter Two”’s move from storytime in one “Chapter Two,” to omniscient, critical narrator in another “Chapter Two” (64). In these examples and elsewhere in Scorched Altar, Darling shifts diction and tone, a shifting that offers different speakers that speak from varying points of view, taking up the position of story narrator, literary critic, historian, and sometimes, from an unknown standpoint, such as those from footnoted quotations without sources. These changes in tone are not signaled by structural devices, as they might be in another text that offered footnotes, author’s notes, advance praise, or appendices, but rather appear within the same structure that all tones are delivered. This diction strategy troubles story development, delivery expectation, and cultural significance placed on story as artifact and scholar as artifact’s critical investigator.

Darling also troubles the function of notes and footnotes. In the section from Palimpsest, Darling offers notes and footnotes on the history of a shoe, a locket, a dress, desire, and architecture, suggesting the importance of objects associated with women’s dress and simultaneously questioning the importance placed on areas of intellectual scrutiny and study. Such a selected sequence, both by the structural devices in the poems and the use of established book organizational devices, asks readers to question how books of literary criticism and literature are constructed and to resist readerly expectations of terminology and credibly. Her footnotes, given their displacement from a “real” text, displaces the reader and positions the readers at some distance from the text, a place in which they are unable to gain access to it. This displacement enables the reader to be situated as researcher, traveler, thinker, and speculator and invites the reader to resist the construction of books by the form in which the poems and stories are delivered in Scorched Altar.

Like Darling’s new book, The Sun & The Moon (BlazeVOX, 2014), Darling’s poems concern themselves with storytime. Time signals movement to action, a memory, or connection to others. In “‘I was lit from the inside” from Night Songs, she writes, “That was when the curtain fell” (13). Time signaling phrases like “that was when” move the plot of the poems from description to action. They are also a storytelling device that indicate a narrator outside of the sequence’s storytime. Elsewhere, time is signaled by memory in a reflection. The line “She recalled the thin wood railing from her last visit” (20) takes the story to a flashback of a similar musical encounter. Time also signals the movement of the self towards others. In “The Cello” Darling writes, “Before I knew it, you were there,” (14) connecting the speaker to the arrival of a companion. Likewise in “Ennui” she writes, “when I ask why the rooms buzz with damselflies, you merely nod your head” (18). Time here allows the reader to see the emotional disconnect between characters. Such concern with time signals an unfolding of events in the sequence that moves the narrative forward, develops the backstory, and creates the emotional pitch of the characters’ relationship. However, cataloging time calls attention to it and asks the reader to consider how and why time moves in a given way within a story and if time is necessary for action, memory, and connection.

An overarching theme in Darling’s Scorched Altar is love, but one permeated by a disconnect that evokes lack. Though Darling cautions in the sequence from Requited, “Why can so many things be mistaken for metaphor” (135), Darling’s characterization of love works as a trope to read her thinking about books. Darling’s persistent questioning of the book and the art of story structure suggests she, too, like her readers, adores the idea of story, but finds that it falls short of what it promises to deliver. Yet Darling’s resistance to its construction offers other ways to tell stories, to document love and affection, and to question story making devices. Eloquently, provocatively, and strategically, Scorched Altar reimagines the book.

Paperback: 178 pages

Publisher: BlazeVOX Books (2015)

Purchase: Available at BlazeVOX

“She wanted to understand the innermost workings of this elaborate machine”: Scorched Altar Review by Laura Madeline Wiseman

Rich with sensory details and scene, Kristina Marie Darling’s new book Scorched Altar collects work from twelve previous collections and invites readers to fragment their expectations of book structure, much as she fragments the structure of her sentences. She writes, “My cold blue lips” (134), “Fallen branches. A dead hummingbird” (124), “An uncanny brightness in every window” (105), and “The door to the gallery groaning on its hinges” (27). Indeed, Darling is positing a metaphorical loss and death of the book by opening it, an opening that suggests books are stuck in one manner of delivery. To accomplish this, Darling’s explores a book’s structural devices such as glossaries, diction and tone, notes and footnotes, time’s function within storytelling, and the theme of love and affection.

Darling troubles the stability of language by defining terms within a glossary. In “A History of Melancholia: Glossary of Terms” from The Body is a Little Gilded Cage, Darling defines a set of terms (e.g. locket, memento, nightingale) that are dependent on the text, rather than dependent on the dictionary, or a larger cultural context, positioning the reader of her text as not native to the English language, contemporary culture, or the romantic world within the story. She writes, “nightingale A harbinger of both despair and onslaught of winter. Its bright mornings and colorless evenings” (55). Darling explores themes of courtship and objects of affections, as well as the metaphor of wedded woman as caged bird within the poem, but from the position of outsider.

Darling also explores the use of tone and diction within books. The poem “Palimpsest” from Compendium gives shifts in diction, literary criticism, description, and story. In the second “Chapter One” description, she writes, “His appearance may be read as a culmination of several recurring motifs” (27), taking up the linguistic phrasing of scholarship. Likewise in the selection from Palimpsest, the “Chapter Two”’s move from storytime in one “Chapter Two,” to omniscient, critical narrator in another “Chapter Two” (64). In these examples and elsewhere in Scorched Altar, Darling shifts diction and tone, a shifting that offers different speakers that speak from varying points of view, taking up the position of story narrator, literary critic, historian, and sometimes, from an unknown standpoint, such as those from footnoted quotations without sources. These changes in tone are not signaled by structural devices, as they might be in another text that offered footnotes, author’s notes, advance praise, or appendices, but rather appear within the same structure that all tones are delivered. This diction strategy troubles story development, delivery expectation, and cultural significance placed on story as artifact and scholar as artifact’s critical investigator.

Darling also troubles the function of notes and footnotes. In the section from Palimpsest, Darling offers notes and footnotes on the history of a shoe, a locket, a dress, desire, and architecture, suggesting the importance of objects associated with women’s dress and simultaneously questioning the importance placed on areas of intellectual scrutiny and study. Such a selected sequence, both by the structural devices in the poems and the use of established book organizational devices, asks readers to question how books of literary criticism and literature are constructed and to resist readerly expectations of terminology and credibly. Her footnotes, given their displacement from a “real” text, displaces the reader and positions the readers at some distance from the text, a place in which they are unable to gain access to it. This displacement enables the reader to be situated as researcher, traveler, thinker, and speculator and invites the reader to resist the construction of books by the form in which the poems and stories are delivered in Scorched Altar.

Like Darling’s new book, The Sun & The Moon (BlazeVOX, 2014), Darling’s poems concern themselves with storytime. Time signals movement to action, a memory, or connection to others. In “‘I was lit from the inside” from Night Songs, she writes, “That was when the curtain fell” (13). Time signaling phrases like “that was when” move the plot of the poems from description to action. They are also a storytelling device that indicate a narrator outside of the sequence’s storytime. Elsewhere, time is signaled by memory in a reflection. The line “She recalled the thin wood railing from her last visit” (20) takes the story to a flashback of a similar musical encounter. Time also signals the movement of the self towards others. In “The Cello” Darling writes, “Before I knew it, you were there,” (14) connecting the speaker to the arrival of a companion. Likewise in “Ennui” she writes, “when I ask why the rooms buzz with damselflies, you merely nod your head” (18). Time here allows the reader to see the emotional disconnect between characters. Such concern with time signals an unfolding of events in the sequence that moves the narrative forward, develops the backstory, and creates the emotional pitch of the characters’ relationship. However, cataloging time calls attention to it and asks the reader to consider how and why time moves in a given way within a story and if time is necessary for action, memory, and connection.

An overarching theme in Darling’s Scorched Altar is love, but one permeated by a disconnect that evokes lack. Though Darling cautions in the sequence from Requited, “Why can so many things be mistaken for metaphor” (135), Darling’s characterization of love works as a trope to read her thinking about books. Darling’s persistent questioning of the book and the art of story structure suggests she, too, like her readers, adores the idea of story, but finds that it falls short of what it promises to deliver. Yet Darling’s resistance to its construction offers other ways to tell stories, to document love and affection, and to question story making devices. Eloquently, provocatively, and strategically, Scorched Altar reimagines the book.

Laura Madeline Wiseman is the author of Some Fatal Effects of Curiosity and Disobedience (Lavender Ink, 2014), Queen of the Platform (Anaphora Literary Press, 2013), Sprung (San Francisco Bay Press, 2012), and the collaborative book Intimates and Fools (Les Femmes Folles Books, 2014) with artist Sally Deskins, as well as two letterpress books, and eight chapbooks, including Spindrift (Dancing Girl Press, 2014). She is the editor of Women Write Resistance: Poets Resist Gender Violence (Hyacinth Girl Press, 2013). Wiseman has a doctorate from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. She has received an Academy of American Poets Award, the Wurlitzer Foundation Fellowship, and her work has appeared in Prairie Schooner, Mid-American Review, Margie, and Feminist Studies. Visit her website at www.lauramadelinewiseman.com