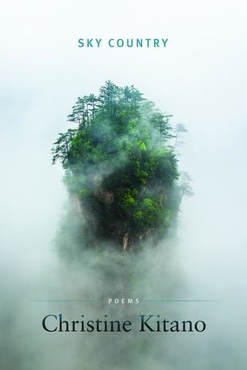

Sky Country by Christine Kitano

Paperback: 104 pgs.

Publisher: BOA Editions (2017)

Purchase @ BOA Editions

Review by Travis Chi Wing Lau.

“How terrible it is to contemplate, once again, that the government itself might once more be the very instrument of terror and division. That cannot happen again. We cannot allow it,” writes George Takei, a Japanese American actor and activist, in an op-ed for the Washington Post about the implications of Trump’s Muslim ban. His question is actually rather simple: have we learned nothing from our collective past? By invoking the legacy of Japanese internment, Takei underscores just how intrinsic amnesia is to the ongoing project of marginalization and oppression of minority populations. Those in power and those in bed with them desperately want us to forget, want us to misremember its misdeeds. Kitano’s volume refuses this amnesia by its insistence on memory. For each of the figures in Sky Country, remembering is not a choice but an inevitability. “We are built for life,” Kitano writes, “for love, which means / we are built for pain.” Kitano’s generosity is in letting us read our way toward this lesson.

Kitano’s poetic method is one of tender animacy. Those that she invests with a voice, with energy, witness the too often silenced intergenerational experience of historical trauma and its disturbing reverberations into the present. What we confront, as readers, is the crushing interiority of those displaced, the affective density of longing of “an empty house, an empty / field, an orchard emptying / of fruit” (26). The stories recollected are tragically familiar, yet they are too often deliberately forgotten for the preservation of future generations:

For the sake of the children.

we’ll teach them to forgive the fears of others,

the offenses. But what we don’t anticipate

is how the dust of the desert will clot our throats,

how much fear will conspire to keep us silent.

And how our children will read this silence

as shame… (23)

These lines betray the fact that such willful forgetting is actually impossible; it becomes a visceral blockage, a kind of impasse that is irreconcilable precisely because it has real effects on the bodies of those that remember even in spite of the benevolent intent to protect the children from the truth. Kitano’s verses capture the painful extent to which Issei and Nisei (first- and second-generation Japanese Americans) had to endure their experience in silence. In place of narrative representations of Topaz Concentration Camp, we are given the perversity of its landscape, freighted with “skeletal trees,” and “mountains” “turned away.” The landscape of memory is fleeting yet turgid. The space of the camp seems to be a character of its own, one that bears a troubled relationship to the human actors that have been relegated to the camp. The camp transforms all of its captives, and Kitano describes precisely how.

Kitano importantly gives voice to the distinctly female experience of internment and their stoicism in the face of profound suffering. In “Lucy Come Hawai’i,” we see how:

When night arrives in camp, you offer the men

your white body: their callused hands root

through the humid dark for flesh untouched

by sun. They crave your breath, your cool hands

smooth as abalone shell, your fine feet

two slim canoes. While their wives sleep,

blistered from stripping cane in the sun,

swathed fields, robes slip with a shiver

from your slender shoulders. Shoulders like

slices of white melon from back home, your cheeks

the pink blossoms from their childhood trees.

Kitano fleshes out the “comfort woman” narrative, the burden of womanhood in the camp as not only caretaker but also sexual object. This will translate into the struggle of a daughter’s expectations, a mother’s experience of childbirth, a wife’s dissolution of her marriage, the kind of silent “grief you bear alone” (71). Kitano never fails to highlight how these experiences are distinctly gendered and often managed as a kind of unspoken affective labor that gets passed on generationally. “I know I’m not the daughter my mother wants, but I still don’t know who or what she wants me to be” (57). The expectations and aspirations remain unclear because they are so colored by the experience of trauma, loss, and displacement.

I sat for a long time with the opening poem of the second movement, “Gaman.” As Kitano herself cites, gaman is a Japanese term “meaning to endure, persist, persevere, / or to do one’s best in times of frustration and adversity” (22). Such spirit of endurance characterizes much of the Japanese internment experience, yet Kitano problematizes it by tying it to the aspirational experience of Asian Americans. The promise of the American Dream is revealed repeatedly to be what Lauren Berlant has termed “cruel optimism,” or a relation to something you desire that actually becomes an obstacle to your flourishing. The desire for financial security, for cultural assimilation becomes a perverse kind of gaman:

For stealing day-old donuts, my mother is fired from her first

American job, cleaning offices in a downtown Los Angeles high-rise.

Still this is America. America is good, she says. You don’t know how

good you have it here. (16)

In comparison to the unspeakable experiences of grandmothers fleeing Korea and Japan, “America is good.” But Kitano leaves us questioning this “good” and its accessibility to those like Kitano’s grandmothers. Is their gaman ultimately futile, particularly with our current political climate? Go on, Kitano entreats her grandmother. As her readers, we learn of the consequences and costs of gaman even as a “light / approaches, out of shadow” (71).

Christine Kitano is the author of Sky Country (BOA Editions, Fall 2017) and Birds of Paradise (Lynx House Press, 2011). She received her BA from the University of California, her MFA from Syracuse University, and her PhD in English and Creative Writing from Texas Tech University. She was born and raised in Los Angeles, CA, and currently lives in Ithaca, NY, where she is an assistant professor of creative writing, poetry, and Asian American literature at Ithaca College.