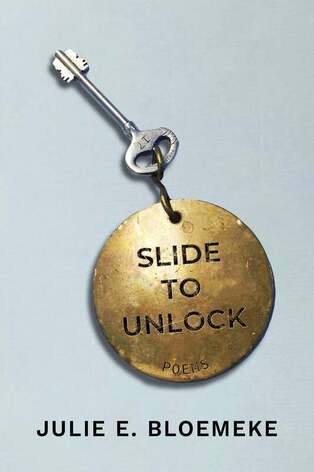

Slide to Unlock by Julie E. Bloemeke

Review by Alina Stefanescu.

Slide to Unlock consumed me. By layering first person pronouns, complicating their relationship to memory, Julie E. Bloemeke foregrounds questions of agency, complicity, and loyalty. She does this at the level of the line as well as the book. She does this carefully, recklessly, with immaculate control, palpating the conventions of fidelity in romantic relationships and their relation to the self across time.

Fidelity, or the quality of faithfulness, comes to us from the Latin word fidēlis, which describes a state of being bound by fealty. The oath, or fides, is integral to this notion of duty; the power of the word to form a bond. Bloemeke's poems explore this tension between words, bonds, bondage, and loyalty in what feels like an intimate, first-person voice, though I would argue that the role of time and technology challenges the intimate "I" here.

The title poem, "Slide to Unlock," addresses the reader with a collective pronoun, a We that implicates from the outset. This complicit We creates a frame for how our iphones inhabit us, altering time, bringing a google map closer to the whisper and the image, blurring boundaries between experience and knowing. What is the significance of the word in wi-fi, iphone world? How has meaning been changed by the medium?

Borrowing the lexicon of phone communication, Bloemeke invokes time with respect to how we spoke across distances and particular phone technologies. The sections are titled in this way: "Dialing-In", "Call Waiting", "On the Line", and "Cellular", among others. With its brief, staccato couplets and short lines, "Rotary Ode" layers conditionals and abruptness which mimics the feel of those heavy silences I remember from rotary phones, as in:

How we could

pick up

with silence

blame the line.

She also uses geographical places to address their particular co-memorants, those who remembered the time and place past. "Glass City" revisits Toledo, decades after, and winds along in couplets before it switches from the declarative mode ("Look: when I hold it all") to an uncertain, whispering interrogative:

I will call on the I, the you,

our past, this city.

By gently destabilizing pronouns, the narrator's voice is rendered unreliable. Identity feels murky, uncertain, fascinating. Again in "Finger Sequence in Blue," the referents are rendered uncertain. I felt them as the early pronouns of high school years, the scarcely-inhabited pronouns that spoke more to what others expected of us (and how well we fulfilled those expectations) than our presence in them:

I used a you. You used a me, too.

The nostalgia for non-digital analog, or a time when we were less accessible to one another, appears in "You're Breaking Up," spoken to an Us, possibly an ex, someone whose shared silence was significant:

And how neither of us ever hung up

falling asleep over the wires, waking

in the morning, the receiver somehow still

and dead on the pillow next to each of us.

There is no single "We", no definitive "Us," no penultimate pronoun to bind the poems. In "Pulse Storm, 2008," the narrator seeks a memory of someone, asks him: "Why are we never enough?" This desire to identify the We speaks directly to the feminine socialization which encourages us to define the I as part of a relationship, conditioned by the amatonormative gaze--to be seen as someone's girl. Which is to say that these poems interrogate femininity, making the noun, muse, a site of conflict and contention.

In "Letters On the Air (I Feel Love)," the poet’s sprawling, expansive use of the field puts us directly in the seventeen-year-old self, dancing to Donna Summer, discovering the pleasure of dancing for someone, for the freedom of no-one-yet ("the imagined man in the chair"), for the thrill of his gaze. Already, the poet acknowledges how "this voice makes" her "another word for muse." But who is using who? Do we miss the girls we were in their eyes--or the girls we imagined ourselves into being?

I think questions of objectivity and subjectivity engage the construction of self across time: blurred lines of looking back, of re-visioning; the complex You/I relations address both the girl she used to be and those who loved her, who saw her. And the decision to write this self, to speak to these selves, is a form of reclamation. But Bloemeke is doing more; she is also asking how use (or muse-making) changes in new technological mediums. How does the ability to text a nude alter the imaginative and fantastical stakes in the game of phone romance?

In "The Call," the iphone, itself, carries the duty of fidelity, a close attention facilitated by easy access. The poet addresses an absent You, an ex or a column of exes, in direct comparison to her husband's faithfulness:

When he says the word, the word

is the word. The word isn't only love,

it is my collapse into this bed

that folds me in its mouth,

never leaves my faulty wires

frayed with hope, disconnected,

ringing, ringing in the blank

and forgotten dark.

The interplay among modes of communication occurs at both symbolic and sonic levels. For example, ring elicits the symbolic duty of marriage as well as a Siren-like summoning which elicits the rotary calls of the past. I paused a few times to wonder which ring is calling. I also wondered how high-fidelity and lo-fidelity, as descriptions of sound recordings, speak to faithfulness at the level of memory. A high-fidelity recording is one where the copy reproduces its source more accurately. The lo-fidelity, analog calls are the furthest, the hardest to recollect--and the easiest to idealize, to render safe and familiar.

In "Gospel of Texts, Books I-IV," Bloemeke collages the memories of "sent cells" through the medium of text messages. The vaguely ekphrastic sketches of texted photos, the shadows of the images themselves elided and yet encountered as intimacy. All can be read into "two birds / crossing." Love can be made from a mountain if one eyes the slope closely enough. Working and re-working certain images increases their intensity, magnifies the implications and subtexts, and it is this imagining which feels unfaithful. And yet imagining is the work of poetry, the brush-strokes of memory shaping encounters into landscapes, interceding in the present.

So: yes. Imagine a bookstore, a place in Paris. Imagine a photo of her face, a man's hand under her chin, his eyes the camera. The poet wants to understand what has changed in us, in our loves, in our ways of relating across time. Paris, the pin of a map on a city, the spaces whether others can "unlock us." The Paris poems, the blue chair, these objects marking how possession changes over time, and the claims we lay to others grows stranger in knowing them, in knowing what we gave up for what we got. It is a lot. And Lot's wife is to look backwards. And part of me wanting so much at this point in the book to send a quick text to Julie: Be careful. Just be so careful when you turn to look back.

*

In Fidelity. I leave a space between the words which have not been joined as indictment. To act in fidelity is to be true to a vow, to keep one's word, or act in accordance with it. Infidelity is what occurs when less than an inch of space is erased, and closeness results. All these memories of being seen and having seen rise like monuments--the love we marry into vows forever routed through the boy we loved first, the one with whom we dreamt of Eiffel Towers. And that love is still there in the first fleshed glimpse of the monument.

I am fascinated by the speech-acts in these poems, particularly the relationship between epistolary forms, memory, and technology, how Bloemeke's use of the epistolary is sharpened into a dramatic act resembling the soliloquy.

The poet and the muse text photos back and forth, she and he, and the question of fidelity exists in each intimate remembering--are we faithful to the men we married if we cannot deny they married us? The opposite of fidelity is infidelity. The relationship between fidelity and vow is centered in "Vow," where the poet addresses her husband:

You say I am a place

lifted from every geography.

"Letter to My Husband" addresses the silent muse, or the partner who allows us to write from the fullness of time which includes memory--which includes ghosts. It begins in an end-stopped line, a supplication--"Forgive me, husband."--and then continues into slight apologia:

You held me as I called

his name, rinsed him through me, polished

my stone of regret. And still, you loved

the fertile, broken girl, even as she claimed him.

For it is "the incantation of questions left open" that protects poetry from becoming another margin in the multiple forgettings of therapeutic american self-help. In the end-notes, Bloemeke rededicates this poem to the man who "willingly chose to love an artist all of those years ago, knowing even then that part of me would always be rooted in memory, story, and poetry." In this final poem, Monet's painting, "Antibes Seen From Le Solis," is set up as an ekphrastic frame, again, a placed coordinate. "Blue Note" reveals the poet speaking to he who first wandered that space with her, working from a neo-confessional mode where the "I" comes first; the "I" carries both the memory and the responsibility of its proximity.

I leave the words: betrayal, infidelity.

I leave the years of apology, the nights

my empty hands sought the air for you,

resolution. I find the blue chair.

I will not remember what I wrote,

The anaphora, "I leave," thickens the tone of reckless, tender urgency threaded throughout these poems. And the ring returns in a reference to the film, Before Sunset:

Always this is how I see us: that precipice

of possible. It makes no sense. I am betrothed

to another life. Yet the ring is not a lock.

Some things in me cannot be held.

I married a man that knew this and somehow

blessed my brokenness: always part of me

is you. And he loves me still.

All the loves swarm back like insects to a screen door. It is trangressive to say this. There are entire self-help shelves and industries devoted to emotional infidelity. Self-help takes us more space than poetry in big-box bookstores. There is no market for longing--only for erasure, often sold as resolution through forgetting. I remain haunted by these poems, by the faithfulness of what they accomplish in fidelity.

Slide to Unlock consumed me. By layering first person pronouns, complicating their relationship to memory, Julie E. Bloemeke foregrounds questions of agency, complicity, and loyalty. She does this at the level of the line as well as the book. She does this carefully, recklessly, with immaculate control, palpating the conventions of fidelity in romantic relationships and their relation to the self across time.

Fidelity, or the quality of faithfulness, comes to us from the Latin word fidēlis, which describes a state of being bound by fealty. The oath, or fides, is integral to this notion of duty; the power of the word to form a bond. Bloemeke's poems explore this tension between words, bonds, bondage, and loyalty in what feels like an intimate, first-person voice, though I would argue that the role of time and technology challenges the intimate "I" here.

The title poem, "Slide to Unlock," addresses the reader with a collective pronoun, a We that implicates from the outset. This complicit We creates a frame for how our iphones inhabit us, altering time, bringing a google map closer to the whisper and the image, blurring boundaries between experience and knowing. What is the significance of the word in wi-fi, iphone world? How has meaning been changed by the medium?

Borrowing the lexicon of phone communication, Bloemeke invokes time with respect to how we spoke across distances and particular phone technologies. The sections are titled in this way: "Dialing-In", "Call Waiting", "On the Line", and "Cellular", among others. With its brief, staccato couplets and short lines, "Rotary Ode" layers conditionals and abruptness which mimics the feel of those heavy silences I remember from rotary phones, as in:

How we could

pick up

with silence

blame the line.

She also uses geographical places to address their particular co-memorants, those who remembered the time and place past. "Glass City" revisits Toledo, decades after, and winds along in couplets before it switches from the declarative mode ("Look: when I hold it all") to an uncertain, whispering interrogative:

I will call on the I, the you,

our past, this city.

By gently destabilizing pronouns, the narrator's voice is rendered unreliable. Identity feels murky, uncertain, fascinating. Again in "Finger Sequence in Blue," the referents are rendered uncertain. I felt them as the early pronouns of high school years, the scarcely-inhabited pronouns that spoke more to what others expected of us (and how well we fulfilled those expectations) than our presence in them:

I used a you. You used a me, too.

The nostalgia for non-digital analog, or a time when we were less accessible to one another, appears in "You're Breaking Up," spoken to an Us, possibly an ex, someone whose shared silence was significant:

And how neither of us ever hung up

falling asleep over the wires, waking

in the morning, the receiver somehow still

and dead on the pillow next to each of us.

There is no single "We", no definitive "Us," no penultimate pronoun to bind the poems. In "Pulse Storm, 2008," the narrator seeks a memory of someone, asks him: "Why are we never enough?" This desire to identify the We speaks directly to the feminine socialization which encourages us to define the I as part of a relationship, conditioned by the amatonormative gaze--to be seen as someone's girl. Which is to say that these poems interrogate femininity, making the noun, muse, a site of conflict and contention.

In "Letters On the Air (I Feel Love)," the poet’s sprawling, expansive use of the field puts us directly in the seventeen-year-old self, dancing to Donna Summer, discovering the pleasure of dancing for someone, for the freedom of no-one-yet ("the imagined man in the chair"), for the thrill of his gaze. Already, the poet acknowledges how "this voice makes" her "another word for muse." But who is using who? Do we miss the girls we were in their eyes--or the girls we imagined ourselves into being?

I think questions of objectivity and subjectivity engage the construction of self across time: blurred lines of looking back, of re-visioning; the complex You/I relations address both the girl she used to be and those who loved her, who saw her. And the decision to write this self, to speak to these selves, is a form of reclamation. But Bloemeke is doing more; she is also asking how use (or muse-making) changes in new technological mediums. How does the ability to text a nude alter the imaginative and fantastical stakes in the game of phone romance?

In "The Call," the iphone, itself, carries the duty of fidelity, a close attention facilitated by easy access. The poet addresses an absent You, an ex or a column of exes, in direct comparison to her husband's faithfulness:

When he says the word, the word

is the word. The word isn't only love,

it is my collapse into this bed

that folds me in its mouth,

never leaves my faulty wires

frayed with hope, disconnected,

ringing, ringing in the blank

and forgotten dark.

The interplay among modes of communication occurs at both symbolic and sonic levels. For example, ring elicits the symbolic duty of marriage as well as a Siren-like summoning which elicits the rotary calls of the past. I paused a few times to wonder which ring is calling. I also wondered how high-fidelity and lo-fidelity, as descriptions of sound recordings, speak to faithfulness at the level of memory. A high-fidelity recording is one where the copy reproduces its source more accurately. The lo-fidelity, analog calls are the furthest, the hardest to recollect--and the easiest to idealize, to render safe and familiar.

In "Gospel of Texts, Books I-IV," Bloemeke collages the memories of "sent cells" through the medium of text messages. The vaguely ekphrastic sketches of texted photos, the shadows of the images themselves elided and yet encountered as intimacy. All can be read into "two birds / crossing." Love can be made from a mountain if one eyes the slope closely enough. Working and re-working certain images increases their intensity, magnifies the implications and subtexts, and it is this imagining which feels unfaithful. And yet imagining is the work of poetry, the brush-strokes of memory shaping encounters into landscapes, interceding in the present.

So: yes. Imagine a bookstore, a place in Paris. Imagine a photo of her face, a man's hand under her chin, his eyes the camera. The poet wants to understand what has changed in us, in our loves, in our ways of relating across time. Paris, the pin of a map on a city, the spaces whether others can "unlock us." The Paris poems, the blue chair, these objects marking how possession changes over time, and the claims we lay to others grows stranger in knowing them, in knowing what we gave up for what we got. It is a lot. And Lot's wife is to look backwards. And part of me wanting so much at this point in the book to send a quick text to Julie: Be careful. Just be so careful when you turn to look back.

*

In Fidelity. I leave a space between the words which have not been joined as indictment. To act in fidelity is to be true to a vow, to keep one's word, or act in accordance with it. Infidelity is what occurs when less than an inch of space is erased, and closeness results. All these memories of being seen and having seen rise like monuments--the love we marry into vows forever routed through the boy we loved first, the one with whom we dreamt of Eiffel Towers. And that love is still there in the first fleshed glimpse of the monument.

I am fascinated by the speech-acts in these poems, particularly the relationship between epistolary forms, memory, and technology, how Bloemeke's use of the epistolary is sharpened into a dramatic act resembling the soliloquy.

The poet and the muse text photos back and forth, she and he, and the question of fidelity exists in each intimate remembering--are we faithful to the men we married if we cannot deny they married us? The opposite of fidelity is infidelity. The relationship between fidelity and vow is centered in "Vow," where the poet addresses her husband:

You say I am a place

lifted from every geography.

"Letter to My Husband" addresses the silent muse, or the partner who allows us to write from the fullness of time which includes memory--which includes ghosts. It begins in an end-stopped line, a supplication--"Forgive me, husband."--and then continues into slight apologia:

You held me as I called

his name, rinsed him through me, polished

my stone of regret. And still, you loved

the fertile, broken girl, even as she claimed him.

For it is "the incantation of questions left open" that protects poetry from becoming another margin in the multiple forgettings of therapeutic american self-help. In the end-notes, Bloemeke rededicates this poem to the man who "willingly chose to love an artist all of those years ago, knowing even then that part of me would always be rooted in memory, story, and poetry." In this final poem, Monet's painting, "Antibes Seen From Le Solis," is set up as an ekphrastic frame, again, a placed coordinate. "Blue Note" reveals the poet speaking to he who first wandered that space with her, working from a neo-confessional mode where the "I" comes first; the "I" carries both the memory and the responsibility of its proximity.

I leave the words: betrayal, infidelity.

I leave the years of apology, the nights

my empty hands sought the air for you,

resolution. I find the blue chair.

I will not remember what I wrote,

The anaphora, "I leave," thickens the tone of reckless, tender urgency threaded throughout these poems. And the ring returns in a reference to the film, Before Sunset:

Always this is how I see us: that precipice

of possible. It makes no sense. I am betrothed

to another life. Yet the ring is not a lock.

Some things in me cannot be held.

I married a man that knew this and somehow

blessed my brokenness: always part of me

is you. And he loves me still.

All the loves swarm back like insects to a screen door. It is trangressive to say this. There are entire self-help shelves and industries devoted to emotional infidelity. Self-help takes us more space than poetry in big-box bookstores. There is no market for longing--only for erasure, often sold as resolution through forgetting. I remain haunted by these poems, by the faithfulness of what they accomplish in fidelity.

|

Julie E. Bloemeke received her MFA through the Bennington Writing Seminars and an MA from the University of South Carolina. She has been a fellow at the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts and also in residency at the Bowers House Literary Center. Her poems have been widely anthologized and appeared in numerous literary journals including Gulf Coast, Prairie Schooner, Poet Lore, and others. Her ekphrastic work has been published and showcased in collaborations with the Toledo Museum of Art and Phoenix Museum of Art. A freelance writer, editor, and guest lecturer, her interviews have recently appeared in The AWP Writer’s Chronicle and in Poetry International. Slide to Unlock was a finalist and semi-finalist for multiple book prizes including the May Swenson Poetry Prize in 2016. It is her first full-length poetry collection. |