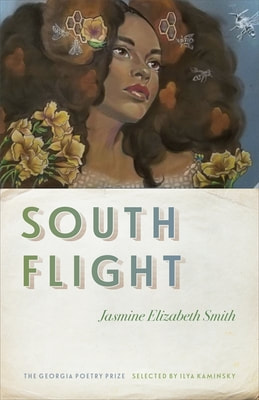

South Flight by Jasmine Elizabeth Smith

South Flight by Jasmine Elizabeth Smith

Paperback: 104 pgs

Publisher: University of Georgia Press (2022)

Purchase @ University of Georgia Press

Paperback: 104 pgs

Publisher: University of Georgia Press (2022)

Purchase @ University of Georgia Press

Review by Rhiannon Thorne.

“All Us Wind Up Being Kindling for Someone Else’s Fire”:

A Review of Jasmine Elizabeth Smith’s South Flight

As a Southern Studies scholar, I spend a lot of time meditating on “what is The South?” But it is a question that I doubt many, especially those outside of The South (whatever that is), ever ask. It may even surprise you to know that which states or areas are designated “The South” is contestable. If you’ve never thought about it, ask yourself: Is the South only comprised of states that joined the Confederacy during the U.S. Civil War or is it comprised of all slave-holding territories circa 1861? Can The South be urban? A tech hub?

The U.S. Federal Government defines The South as comprising all of: Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, the District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia. The Ringer’s 2017 “Sorry, but Your State Is Not the South” (a typical representation of the types of debates you hear down here in Louisiana—indisputably Deep South), focuses on ousting from the region: Kentucky and Oklahoma[1] are both booted due to their “plains-ness,” “Modern Texas” and Atlanta are rejected for their urbaneness, Florida is described as “it’s complicated,” and Missouri—never once considered a Southern State by the federal government—is, by its inclusion on this exclusive list, aligned with The South even as it is simultaneously denied claim to the region.

I bring up this debate only to illuminate the malleability of The South and a commonly held belief in my field: The South is a construct—it is what we say it is—and what we decide is The South we decide to serve a particular purpose.

Enter Jasmine Elizabeth Smith’s South Flight into this fray. Smith’s opening poem, “Blacktown Blues of Oklahoma” ends:

I be first to admit this ain’t no gospel,

but might my song, simple

it may be, choir droves up yard,

quicken Oklahoman air prairie.

I pray my eyes wring witness,

twenty-one freshwater routes

against forgetting this home

I call South.

(3)

What follows is a collection deeply invested in Oklahoma as The South. From attention to foodways and land to blues and the undead, these poems trade on staple Southern Literature tropes and I am here for it. Set around the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921, South Flight’s staked claim for Oklahoma as a Southern space not only serves as a glaring reminder of its Jim Crow apartheid but also allows Smith to complicate how we think of this period and this space.

Reading like a blending of Toni Morrison’s lush prose with Langston Hughes’s jazz poems, this collection bears witness to the day-to-day heartaches and fortitude of those living under such oppression. It attends most directly to the lovers Beatrice and Jim who are separated as Jim heads to the industrialized North. From Chicago, Jim writes of their love in Boley, Oklahoma:

in your midst, how a man keen to forget

even the dirt floors of his place

belong to someone else.

(“Correspondence from Chicago, Illinois, to Boley, Oklahoma” 47)

Smith risks mobilizing the idea of The South to highlight the barbarity of Beatrice and Jim’s sociocultural surroundings, but aligning The South with racism is deftly tempered by the poems “For Phillis Wheatley at Water’s Edge,” inspired by an enslaved woman living in Massachusetts in the 18th century, and “Zouzou,” written to the French film’s star, and Missouri native, Josephine Baker:

I heard their trade isn’t much different

from what is done here at home. Only difference

is they prefer their Black rare and chilled over ice,

fine caviars knifed from the ovaries of the South.

(44)

And while Beatrice might end the collection with an imaginary conversation to Jim wherein she tells him “You was brave. Like that you flew away,” we know through Jim’s poems that it was not an easy transition (“Beatrice Makes Shadow Puppetry of Jim on a Sundown Billboard” 78). Likewise, through demonstrated resilience and imaginative space, we witness a strength and bravery in Beatrice for her remaining in Oklahoma—the space where she wishes to be reincarnated, sturdier “as an Old Cypress” (5). This 1920s Oklahoma South is a space both to wish to leave and to return to.

Effectively, any depiction of The South as the container for racial oppression is adroitly dispelled while maintaining focus on the region’s historical atrocities[2].

Overall, Smith enacts the work by Black Feminist Scholars of narrative theorizing, which encourages fleshing out—or building—an archive lost due to systematic oppression and silencing. The late 1910s and early 1920s are often, justifiably, depicted as particularly violent against Black bodies. But, as Smith’s collection demonstrates, the lived experiences for those in such a space as Tulsa, OK cannot be reduced to the bloodshed of systemic lynching.

[1] Never mind the state’s “plains-ness,” The South is not ecologically monolithic, Oklahoma as a Southern Space is historically sticky, too. A Native American territory at the time of the U.S. Civil War, Oklahoma’s so-called Five Civilized Tribes joined the Confederate army but the territory itself did not join the Union as a state until 1907—forty years after Confederate defeat.

[2] The South, as a construct, is also accepted as a container used by the U.S. nation state to hold all the country’s perceived backwardness. For example, affiliating segregation with a region stuck in the past enables the greater U.S. to espouse liberal ideology and fantasies of innocence even as white supremacy remains a national problem (see Leigh Anne Duck’s Our Region). Or, as Houston A. Baker Jr. and Dana D. Nelson succinctly put it in their preface to “Violence, the Body, and 'The South,'” “To have a nation of 'good,' liberal, and innocent white Americans, there must be an outland where 'we' know they live: all the guilty, white yahoos who just don’t like people of color.”

“All Us Wind Up Being Kindling for Someone Else’s Fire”:

A Review of Jasmine Elizabeth Smith’s South Flight

As a Southern Studies scholar, I spend a lot of time meditating on “what is The South?” But it is a question that I doubt many, especially those outside of The South (whatever that is), ever ask. It may even surprise you to know that which states or areas are designated “The South” is contestable. If you’ve never thought about it, ask yourself: Is the South only comprised of states that joined the Confederacy during the U.S. Civil War or is it comprised of all slave-holding territories circa 1861? Can The South be urban? A tech hub?

The U.S. Federal Government defines The South as comprising all of: Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, the District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia. The Ringer’s 2017 “Sorry, but Your State Is Not the South” (a typical representation of the types of debates you hear down here in Louisiana—indisputably Deep South), focuses on ousting from the region: Kentucky and Oklahoma[1] are both booted due to their “plains-ness,” “Modern Texas” and Atlanta are rejected for their urbaneness, Florida is described as “it’s complicated,” and Missouri—never once considered a Southern State by the federal government—is, by its inclusion on this exclusive list, aligned with The South even as it is simultaneously denied claim to the region.

I bring up this debate only to illuminate the malleability of The South and a commonly held belief in my field: The South is a construct—it is what we say it is—and what we decide is The South we decide to serve a particular purpose.

Enter Jasmine Elizabeth Smith’s South Flight into this fray. Smith’s opening poem, “Blacktown Blues of Oklahoma” ends:

I be first to admit this ain’t no gospel,

but might my song, simple

it may be, choir droves up yard,

quicken Oklahoman air prairie.

I pray my eyes wring witness,

twenty-one freshwater routes

against forgetting this home

I call South.

(3)

What follows is a collection deeply invested in Oklahoma as The South. From attention to foodways and land to blues and the undead, these poems trade on staple Southern Literature tropes and I am here for it. Set around the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921, South Flight’s staked claim for Oklahoma as a Southern space not only serves as a glaring reminder of its Jim Crow apartheid but also allows Smith to complicate how we think of this period and this space.

Reading like a blending of Toni Morrison’s lush prose with Langston Hughes’s jazz poems, this collection bears witness to the day-to-day heartaches and fortitude of those living under such oppression. It attends most directly to the lovers Beatrice and Jim who are separated as Jim heads to the industrialized North. From Chicago, Jim writes of their love in Boley, Oklahoma:

in your midst, how a man keen to forget

even the dirt floors of his place

belong to someone else.

(“Correspondence from Chicago, Illinois, to Boley, Oklahoma” 47)

Smith risks mobilizing the idea of The South to highlight the barbarity of Beatrice and Jim’s sociocultural surroundings, but aligning The South with racism is deftly tempered by the poems “For Phillis Wheatley at Water’s Edge,” inspired by an enslaved woman living in Massachusetts in the 18th century, and “Zouzou,” written to the French film’s star, and Missouri native, Josephine Baker:

I heard their trade isn’t much different

from what is done here at home. Only difference

is they prefer their Black rare and chilled over ice,

fine caviars knifed from the ovaries of the South.

(44)

And while Beatrice might end the collection with an imaginary conversation to Jim wherein she tells him “You was brave. Like that you flew away,” we know through Jim’s poems that it was not an easy transition (“Beatrice Makes Shadow Puppetry of Jim on a Sundown Billboard” 78). Likewise, through demonstrated resilience and imaginative space, we witness a strength and bravery in Beatrice for her remaining in Oklahoma—the space where she wishes to be reincarnated, sturdier “as an Old Cypress” (5). This 1920s Oklahoma South is a space both to wish to leave and to return to.

Effectively, any depiction of The South as the container for racial oppression is adroitly dispelled while maintaining focus on the region’s historical atrocities[2].

Overall, Smith enacts the work by Black Feminist Scholars of narrative theorizing, which encourages fleshing out—or building—an archive lost due to systematic oppression and silencing. The late 1910s and early 1920s are often, justifiably, depicted as particularly violent against Black bodies. But, as Smith’s collection demonstrates, the lived experiences for those in such a space as Tulsa, OK cannot be reduced to the bloodshed of systemic lynching.

[1] Never mind the state’s “plains-ness,” The South is not ecologically monolithic, Oklahoma as a Southern Space is historically sticky, too. A Native American territory at the time of the U.S. Civil War, Oklahoma’s so-called Five Civilized Tribes joined the Confederate army but the territory itself did not join the Union as a state until 1907—forty years after Confederate defeat.

[2] The South, as a construct, is also accepted as a container used by the U.S. nation state to hold all the country’s perceived backwardness. For example, affiliating segregation with a region stuck in the past enables the greater U.S. to espouse liberal ideology and fantasies of innocence even as white supremacy remains a national problem (see Leigh Anne Duck’s Our Region). Or, as Houston A. Baker Jr. and Dana D. Nelson succinctly put it in their preface to “Violence, the Body, and 'The South,'” “To have a nation of 'good,' liberal, and innocent white Americans, there must be an outland where 'we' know they live: all the guilty, white yahoos who just don’t like people of color.”

Jasmine Elizabeth Smith (she/her) is a Black poet from Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. She received her MFA in Poetry from the University of California in Riverside. She is a Cave Canem Fellow and a recipient of the Glucks Art Fellowship.

Jasmine Elizabeth’s poetic work is invested in the Diaspora of Black Americans in various historical contexts and eras. Her work has been featured in Black Renaissance Noir, POETRY, and LA Review of Books, and Kweli among others. Her debut collection South Flight was named a finalist for the 2020 National Poetry Series and is the winner of the Georgia Poetry Prize. South Flight is forthcoming with the University of Georgia Press in February of 2022.

Smith currently works as an associate guest editor for the Black Earth Institute’s About Place Journal and currently serves on the 25th Anniversary Cave Canem Fellows and Faculty Committee while teaching a variety of English courses in her recent home of South Seattle. In rest, you will find Jasmine trekking about by boot or snowshoe in nature.

Jasmine Elizabeth’s poetic work is invested in the Diaspora of Black Americans in various historical contexts and eras. Her work has been featured in Black Renaissance Noir, POETRY, and LA Review of Books, and Kweli among others. Her debut collection South Flight was named a finalist for the 2020 National Poetry Series and is the winner of the Georgia Poetry Prize. South Flight is forthcoming with the University of Georgia Press in February of 2022.

Smith currently works as an associate guest editor for the Black Earth Institute’s About Place Journal and currently serves on the 25th Anniversary Cave Canem Fellows and Faculty Committee while teaching a variety of English courses in her recent home of South Seattle. In rest, you will find Jasmine trekking about by boot or snowshoe in nature.