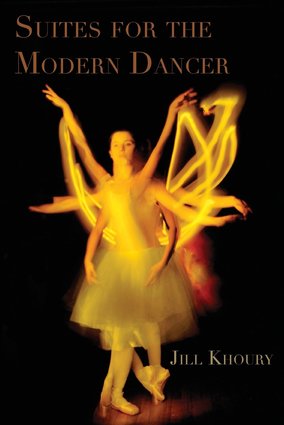

Paperback: 102 pgs

Publisher: Sundress Publications (2016)

Purchase: @ Sundress Publications

Review by Travis Chi Wing Lau

In an interview with Sundress Publications, Jill Khoury describes her personal investment in thinking through the practices of “normalization,” specifically of children’s bodies. “To be like the other kids, and be quiet while I was at it” describes not only how external acts of discipline by figures of authority (in the case of Khoury’s volume, they take the shape of doctors, parents, teachers, peers, and even lovers) enforce certain behaviors but also how they lead to an internalized self-policing that exhaustingly demands unlearning over time. Khoury’s Suites for the Modern Dancer powerfully reveals the violences of discipline on young disabled bodies in a world that continues to espouse ableist notions of normative embodiment.

“Residual Blindness / A Feast for Young Corvids,” revealed in the volume’s notes to be a description of “an exercise given to a child with functional blindness to teach her how to use her remaining eyesight to locate objects,” dramatizes the encounter between teacher and student through a sensory exercise involving beads tossed about the room. The teacher’s refusal to say how many he has just tossed despite the student asking for help is coupled with the child’s (mis)perception that the glass beads are watching and judging her performance. Education seems hardly innocuous – the exercise, otherwise meant to help encourage visually impaired children to make better use of their residual sight and hearing, becomes an alienating ordeal far beyond the simple imperative to “pick them up.” Implied in the exercise’s purpose of deliberately putting disabled children in problem-solving situations is that they, themselves, are problems of development that need correction. Tragically, the speaker self-consciously knows that her body is like her peers’ “but not.”

Khoury builds on this sense of isolation and struggle through her poetic vignettes about a set of young girls: Emma, Annie, Lisa, and Nixi. Particularly haunting is how Khoury represents their gendered experience within spaces ostensibly meant to be safe like the institution, the hospital, the school, or the bedroom. In scenes like Emma’s hospitalization and her subsequent admission into Rose Valley for “24 hour observation” or Lisa’s washing of her charcoal-stained shirt in the Mood Disorders Laundry, Khoury underscores the necessity of thinking about disability from an intersectional standpoint. These disabled women, compelled to “make their bed” as a sign of their “improvement,” are doubly affected by these attempts to diagnose, delimit, and define them as lesser. Rose Valley’s rehabilitative promise seems less about enabling these women to live more fully but about regulating their actions and desires through “security guards, Thorazine, restraints” – all aspects of what we might call the “tyranny of the cure.”

Yet in these visceral “suites”, we see a disability community emerging out of mutual experience. Instead of submission, there is a courageous resistance and consciousness made possible by disability. As opposed to “being quiet,” Khoury’s verses refuse these enduring stigmas against “brittle lives” in favor of new modes of being that enable bodies to be “barely staying within the lines, noisy, curious.”

Publisher: Sundress Publications (2016)

Purchase: @ Sundress Publications

Review by Travis Chi Wing Lau

In an interview with Sundress Publications, Jill Khoury describes her personal investment in thinking through the practices of “normalization,” specifically of children’s bodies. “To be like the other kids, and be quiet while I was at it” describes not only how external acts of discipline by figures of authority (in the case of Khoury’s volume, they take the shape of doctors, parents, teachers, peers, and even lovers) enforce certain behaviors but also how they lead to an internalized self-policing that exhaustingly demands unlearning over time. Khoury’s Suites for the Modern Dancer powerfully reveals the violences of discipline on young disabled bodies in a world that continues to espouse ableist notions of normative embodiment.

“Residual Blindness / A Feast for Young Corvids,” revealed in the volume’s notes to be a description of “an exercise given to a child with functional blindness to teach her how to use her remaining eyesight to locate objects,” dramatizes the encounter between teacher and student through a sensory exercise involving beads tossed about the room. The teacher’s refusal to say how many he has just tossed despite the student asking for help is coupled with the child’s (mis)perception that the glass beads are watching and judging her performance. Education seems hardly innocuous – the exercise, otherwise meant to help encourage visually impaired children to make better use of their residual sight and hearing, becomes an alienating ordeal far beyond the simple imperative to “pick them up.” Implied in the exercise’s purpose of deliberately putting disabled children in problem-solving situations is that they, themselves, are problems of development that need correction. Tragically, the speaker self-consciously knows that her body is like her peers’ “but not.”

Khoury builds on this sense of isolation and struggle through her poetic vignettes about a set of young girls: Emma, Annie, Lisa, and Nixi. Particularly haunting is how Khoury represents their gendered experience within spaces ostensibly meant to be safe like the institution, the hospital, the school, or the bedroom. In scenes like Emma’s hospitalization and her subsequent admission into Rose Valley for “24 hour observation” or Lisa’s washing of her charcoal-stained shirt in the Mood Disorders Laundry, Khoury underscores the necessity of thinking about disability from an intersectional standpoint. These disabled women, compelled to “make their bed” as a sign of their “improvement,” are doubly affected by these attempts to diagnose, delimit, and define them as lesser. Rose Valley’s rehabilitative promise seems less about enabling these women to live more fully but about regulating their actions and desires through “security guards, Thorazine, restraints” – all aspects of what we might call the “tyranny of the cure.”

Yet in these visceral “suites”, we see a disability community emerging out of mutual experience. Instead of submission, there is a courageous resistance and consciousness made possible by disability. As opposed to “being quiet,” Khoury’s verses refuse these enduring stigmas against “brittle lives” in favor of new modes of being that enable bodies to be “barely staying within the lines, noisy, curious.”

Jill Khoury is interested in the intersection of poetry, visual art, representations of gender, and disability. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in numerous journals, including Arsenic Lobster, Copper Nickel, Inter|rupture, and Portland Review. She edits Rogue Agent, a journal of embodied poetry and art. Her chapbook Borrowed Bodies was released from Pudding House Press (2009). Her first full-length collection, Suites for the Modern Dancer, is available from Sundress Publications (2016).