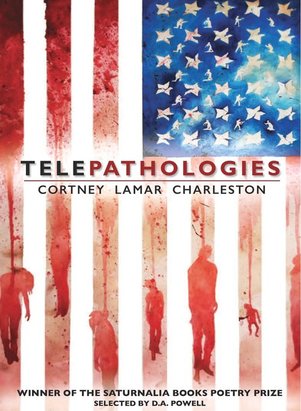

Telepathologies by Cortney Lamar Charleston

Paperback: 136 pages

Publisher: Saturnalia Books (2017)

Purchase @ Amazon

Review by Len Lawson.

Cortney Lamar Charleston testifies to the black experience with all its beauty and tragedy. His poems chronicle contemporary blackness from Miley Cyrus's appropriation of black hip-hop culture, to the household recognition of black individuals murdered in police shootings. Charleston does not shy away from the tough conversations on race in America. He forces more conversation so that readers will continue a pursuit for justice and truth through his art.

In the opening poem “How Do You Raise a Black Child?”, he answers with a thud to the soul in the first line, “From the dead…” If readers have not lived in America over the past five years—let alone four centuries—this would appear to be the punchline of a sick joke. However in reality, black children and adults have been murdered at alarming rates in America. The poem details the places where and how a black child should be cultivated and nurtured: “…With a mama. With a grandmama/ if mama ain’t around…In a house…In the hood…In the suburbs…On a basketball court…” The poem takes almost every possible avenue a black child could be raised and ones outside of him raising himself: “…With hip hop or without. At least with a little Curtis Mayfield, some Motown,/ sounds by Sam Cooke...” The title is like a question in response to a Jeopardy answer, and the poem is the statement before the question. The title and the poem will be the response to many poems in the collection after discussing how the lives of so many black boys, girls, men, and women have been destroyed.

In “State of the Union”, Charleston offers commentary on such events from the seat of President Barack Obama. Amid a tone of fear, disgust, and rage, Charleston invokes the imagery of Obama singing at the memorial for the Emmanuel 9 killed at a church in Charleston, SC.

“…you know nothing of gloom/until you’re mourning strangers with regularity,//going to their televised funerals, watching the first/President of the United States of your kind of citizen sing//a spiritual penned by slave-trading hands, the whole scene/a sum up: our American sins can never be paid for in full.”

Charleston shows the plight and powerlessness of the Commander-in-Chief witnessing police shootings and hate crimes without the ability to affect federal change in cities where they occur. “I would not trade my face for Barack’s black face…I’d suffocate//between the walls of power because power wants me dead”, noting that he survives by the same systems of oppression that kill black people in America: “I joke that it’s his other half that spares him our fate…but I know it’s actually the Secret Service…” Essentially, Charleston reminds readers that no one is above the reproach or the grief that killing black bodies breeds.

With “I’m Not a Racist”, Charleston weaves through the thought process of this title statement from many white Americans. The reasons to be cautious or deliberately vicious toward black people includes “a pack of hoods approaching, loitering,/ acting a littering of public sidewalks” or “to balance a city budget out of wack”. He illustrates the infamous statement “I don’t SEE color” to translate literally not seeing black people in American culture, an avoidance of issues of race. Therefore, as the repeated line “I’m a realist” suggests, to be black in America is to be marginalized and invisible, whereas to be white, especially in a position of power, means to ignore race for the greater good.

In the title poem, Charleston questions the disease of America asking, “How does the body host its sickness?” With plays on the words host and sickness, he depicts various conditions on society that may or may not appear sick to the audience. “…I downloaded a sick tape off DatPiff not even two days ago,/but what was sick about it?” He also plays on the biology of viruses and hosts to attack what is considered normal behavior in society. “…How is that sickness/hosted? Is it anything like a website/is, the Internet just a cancer spread of/ones and zeroes?...” If the human body can be a host for a disease, it can also be eliminated for the cure to take effect, and if this cure takes effect, Charleston asks, “…will you be bedridden with/sickness, or will you step outside healthy?” A thirst for death in media as well as reality has caused Charleston to trace the pathology of such a disease only to find no real cure. If the human host is destroyed which destroys the disease, then death still remains, and the disease mutates all over again.

Cortney Lamar Charleston reports current events in today’s society with a distinct voice for this generation. He writes to take his audience from knowledge to understanding to wisdom. He navigates the boundaries of the page with the skill of a surgeon operating on society’s most challenging maladies. The bill for readers to undergo such procedures is worth consideration.

Publisher: Saturnalia Books (2017)

Purchase @ Amazon

Review by Len Lawson.

Cortney Lamar Charleston testifies to the black experience with all its beauty and tragedy. His poems chronicle contemporary blackness from Miley Cyrus's appropriation of black hip-hop culture, to the household recognition of black individuals murdered in police shootings. Charleston does not shy away from the tough conversations on race in America. He forces more conversation so that readers will continue a pursuit for justice and truth through his art.

In the opening poem “How Do You Raise a Black Child?”, he answers with a thud to the soul in the first line, “From the dead…” If readers have not lived in America over the past five years—let alone four centuries—this would appear to be the punchline of a sick joke. However in reality, black children and adults have been murdered at alarming rates in America. The poem details the places where and how a black child should be cultivated and nurtured: “…With a mama. With a grandmama/ if mama ain’t around…In a house…In the hood…In the suburbs…On a basketball court…” The poem takes almost every possible avenue a black child could be raised and ones outside of him raising himself: “…With hip hop or without. At least with a little Curtis Mayfield, some Motown,/ sounds by Sam Cooke...” The title is like a question in response to a Jeopardy answer, and the poem is the statement before the question. The title and the poem will be the response to many poems in the collection after discussing how the lives of so many black boys, girls, men, and women have been destroyed.

In “State of the Union”, Charleston offers commentary on such events from the seat of President Barack Obama. Amid a tone of fear, disgust, and rage, Charleston invokes the imagery of Obama singing at the memorial for the Emmanuel 9 killed at a church in Charleston, SC.

“…you know nothing of gloom/until you’re mourning strangers with regularity,//going to their televised funerals, watching the first/President of the United States of your kind of citizen sing//a spiritual penned by slave-trading hands, the whole scene/a sum up: our American sins can never be paid for in full.”

Charleston shows the plight and powerlessness of the Commander-in-Chief witnessing police shootings and hate crimes without the ability to affect federal change in cities where they occur. “I would not trade my face for Barack’s black face…I’d suffocate//between the walls of power because power wants me dead”, noting that he survives by the same systems of oppression that kill black people in America: “I joke that it’s his other half that spares him our fate…but I know it’s actually the Secret Service…” Essentially, Charleston reminds readers that no one is above the reproach or the grief that killing black bodies breeds.

With “I’m Not a Racist”, Charleston weaves through the thought process of this title statement from many white Americans. The reasons to be cautious or deliberately vicious toward black people includes “a pack of hoods approaching, loitering,/ acting a littering of public sidewalks” or “to balance a city budget out of wack”. He illustrates the infamous statement “I don’t SEE color” to translate literally not seeing black people in American culture, an avoidance of issues of race. Therefore, as the repeated line “I’m a realist” suggests, to be black in America is to be marginalized and invisible, whereas to be white, especially in a position of power, means to ignore race for the greater good.

In the title poem, Charleston questions the disease of America asking, “How does the body host its sickness?” With plays on the words host and sickness, he depicts various conditions on society that may or may not appear sick to the audience. “…I downloaded a sick tape off DatPiff not even two days ago,/but what was sick about it?” He also plays on the biology of viruses and hosts to attack what is considered normal behavior in society. “…How is that sickness/hosted? Is it anything like a website/is, the Internet just a cancer spread of/ones and zeroes?...” If the human body can be a host for a disease, it can also be eliminated for the cure to take effect, and if this cure takes effect, Charleston asks, “…will you be bedridden with/sickness, or will you step outside healthy?” A thirst for death in media as well as reality has caused Charleston to trace the pathology of such a disease only to find no real cure. If the human host is destroyed which destroys the disease, then death still remains, and the disease mutates all over again.

Cortney Lamar Charleston reports current events in today’s society with a distinct voice for this generation. He writes to take his audience from knowledge to understanding to wisdom. He navigates the boundaries of the page with the skill of a surgeon operating on society’s most challenging maladies. The bill for readers to undergo such procedures is worth consideration.

Cortney Lamar Charleston is originally from the Chicago suburbs. He completed his undergraduate education at the University of Pennsylvania as a member of the Class of 2012, earning a BS in Economics from the Wharton School and BA in Urban Studies from the College of Arts & Sciences; as a student, he focused on the intersection of business and government and the physical and sociological construction of cities. Additionally, it was during this time he began writing and performing poetry as a member of The Excelano Project. His academic background, coupled with his upbringing spent bouncing between Chicago’s South Side and its South and West suburbs undoubtedly influence his written work. Charleston’s poems grapple with matters of race, masculinity, class, heteronormativity, family, body, spirit and how identity is, functionally, a transition zone between all of these competing markers. Said differently, his poetry is a marriage between art and activism, a call for a more involved and empathetic understanding of the diversity of the human experience.