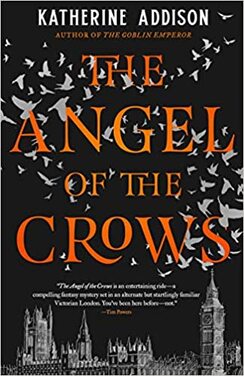

The Angel of the Crows by Katherine Addison

The Angel of the Crows by Katherine Addison

Hardcover: 448 pages

Publisher: Tor Books (2020)

Hardcover: 448 pages

Publisher: Tor Books (2020)

Review by Chey Wollner.

1888, London. A wounded army doctor returns home from Afghanistan and takes up with a brilliant but eccentric room-mate at 221 Baker Street. The promotional material for Katherine Addison’s The Angel of the Crows (2020) says it best from here: “This is not the story you think it is. These are not the characters you think they are.” This is a world populated with vampires and werewolves and angels, all living peacefully alongside humans. Enter Crow—our Sherlock figure—an angel—and Dr. J.H. Doyle—our Watson. The novel follows Crow and Doyle through a number of popular Sherlock Holmes mysteries, held together with the overarching plot to catch

Jack the Ripper. However, the truest part of Addison’s promotional material is this: “This is not the book you are expecting.” Fans of Addison’s The Goblin Emperor

(2014), will be sorely disappointed.

Addison is a master world builder. The Goblin Emperor is a rich fantasy with detailed histories of the monarchy, trade, and public works projects. Addison continues to rely on her strength of world building to craft the fantasy-scape London of The Angel of the Crows. There is an inherent logic to her worldbuilding, and she’s an expert at dispensing information without sounding expository. On the opening page of The Angel of the Crows, readers learn Doyle served in Afghanistan as part of Her Majesty’s Imperial Armed Forces Medical Corps—suggesting this is a world which readers are familiar with. But then, Doyle’s injury: “Two Afghani Fallen led the

charge [...] I should have died [...] and been torn apart by the Fallen’s monstrous claws” (11). These are Fallen angels, and this is Addison’s best use of fantasy, creating a living, breathable logic for her world. This is a world where the man who treats Doyle is famous for treating “spectral injuries” (11), a world where clairvoyance is taught to young girls. In this world, scientific forms of knowledge exist beyond our world’s rational sciences, in ways that are consistent, engaging, and surprising. However, The Angel of the Crows is poorly researched. Even accounting for some steam-punk and alternate history elements, the novel is clearly set in 1880s London. Addison is not able to balance the history of her novel’s era with a responsibility to her twenty-first century readers.

The most irresponsible parts of the novel are Addison’s treatment of Dr. Doyle’s gender, and the harmful narratives about gender and sexuality this novel perpetuates. Doyle can be read as a transgender man—a man assigned female at birth. Doyle dresses as a man, appears socially as a man, and is comfortable throughout the novel being referred to as a gentleman and with he/him pronouns. But Addison makes his gender purposefully ambiguous. In a write-up posted on The Book Smugglers, Addison writes:

You can read Doyle as a trans man, although that term is completely unavailable to the

characters, or you can read Doyle as a transvestite lesbian. Or you can read Doyle as

profoundly genderqueer (also a term not available to the characters) [...] I don’t want to

invalidate any of those readings.[...] I truthfully do not know how Doyle gender-

identifies. (“Queering Dr. Watson: Sexual Identity in The Angel of the Crows”)

Doyle is the first-person narrator of the novel and Addison does not know his gender. And while she is cognizant of the language gap between 1888 and today, she uses outdated language to describe him (if Doyle were a lesbian, perhaps she could find less offensive language to use in an article published in 2020?). In writing this novel, Addison did not do any research on gender or sexuality of the era, at least no research she shared publicly. In her Acknowledgements, Addison’s references are

The Annotated Sherlock Holmes, a list of books on Jack the Ripper, and a few additional sources on murders of the era. Due to her lack of research, Addison’s portrayal

of Doyle’s gender perpetuates a number of harmful narratives.

To start, Doyle’s sex assigned at birth comes as a mid-point plot device. Just before a major section break, Addison gives readers the titillating chapter title; “The Christian Names of Dr. Doyle”, as what the J.H. stood for in Doyle’s name was one of the biggest unsolved mysteries thus far (226). In this chapter, Doyle reveals to his love-interest, Miss Mary Morstan, that he cannot ask to marry her because “‘I am my father’s only daughter”’ (227). Doyle’s gender becomes a plot twist, the final piece of The Sign of the Four reimagining to be unraveled. His gender is not a meaningful exploration of this character’s struggles (or triumphs) with gender

and sexuality in the 1880s because Addison has not considered that line of research.

One of the most insidious problems of using transness as a plot device is that such a notion creates a narrative of trans suffering. When Doyle confesses that he was assigned female at birth to Miss Morstan, he apologizes to her. ‘“I’m sorry,’ I said, knowing full well it was inadequate” (228), suggesting his gender is a fault in his character, a hurt he has caused someone he loves. Miss Morstan then rejects him. “She turned sharply away from me [...] she said, in a voice that could not quite hold steady, ‘I think you had best leave”’ (228). Addison leaves no chance Doyle could be happy in love. In fact, his coming out (and subsequent rejection) becomes

a larger plot point to further the friendship between Crow and Doyle. For, if Doyle and Miss Morstan were to marry, Doyle would not be going on adventures with Crow. And so, rejected, Doyle returns to Baker street, gets drunk and confesses to Crow what happened. This scene works to solidify Crow as an ally to Doyle—the most important relationship either of them have. Yet, Doyle has no human allies who know about him being trans. The only person who doesn’t judge him for his sex assigned at birth is not a person at all. In bringing Crow and Doyle together as the principal relationship of the novel, Addison separates Doyle from loving

human relationships, further othering his gender and experience.

Addison is interested in masculinity as performance, and her novels are typically dominated by cisgender men, who explore masculinity outside of dominant narratives of violence. Yet, she presents Doyle’s gender as quite literal dress-up. After Miss Morstan rejects him, Doyle tells Crow about his struggles ‘“pretending

to be a man”’ (italics added 229). Then, towards the end of the novel, Doyle explains to another angel, ‘“I’ve masqueraded as a man far longer than I wore long skirts and corsets, and I don’t think I could go back. I certainly couldn’t go back to the gossip and embroidery that are a woman’s lot”’ (italics added 435). Pretend; masquerade. GLAAD (Gay and Lesbian Association Against Defamation), groups these words among a list of defamatory language to be avoided when discussing trans people (“Glossary of Terms – Transgender”). And yet Addison presents Doyle as a person who dresses up as a man to escape the difficulties of womanhood. Though Addison acknowledges that not all women amount solely to gossip and embroidery, Doyle still speaks with sexism against women: to be a woman is to have nothing in one’s life except small talk and small tasks. This narrative—that trans men are really women who only wants to escape sexism for male privilege—is a transphobic conversation happening right now with real consequences.

Addison isn’t the only fantasy writer to make uninformed comments about transgender people through her writing. In J.K. Rowling’s essay “J.K. Rowling Writes about Her Reasons for Speaking out on Sex and Gender Issues”—published the same month and year as The Angel of the Crows—Rowling is deeply concerned about “the huge explosion in young women wishing to transition [...] Some say they decided to transition after realising they were same-sex attracted, and that transitioning was partly driven by homophobia.” She goes on to say, “if I’d been born 30 years later, I too might have tried to transition. The allure of escaping womanhood would

have been huge.” (Rowling). Rowling’s fears—that trans men (in particular young trans men) are actually women wishing to escape sexism or homophobia—is paralleled in Addison’s portrayal of Doyle. To be clear, Addison’s treatment of Doyle is not a direct equivalent to the open transphobia of Rowling. However, Addison has a responsibility to be aware of what narratives her writing is pushing forwards.

Addison too, stumbles in her portrayal of sexuality. Crow’s sexuality is poorly researched and contributes to further misinformation for her audiences. Angels, as readers learn, are all female and only take on traditional gender presentations when humans give them a name and a habitation—dominion over a public building (Addison 240). Knowing Crow is also assigned female at birth (though we never really know how or if angels are technically born) provides a new layer of connection between him and Doyle, and does in fact add to Addison’s overarching argument that “Both Doyle and Crow are performing Victorian normative masculinity, but

neither one of them fits it” (“Queering Dr. Watson”). However, angels are also asexual— individuals who do not experience sexual attraction—and Addison makes false claims conflating sexuality and gender. When Crow explains to Doyle that all angels are female, he adds, ‘“Insofar as it makes sense to apply gender to asexual beings”’ (Addison 240). Except, asexuality is like any other sexual orientation: a person can be asexual and be any gender. This moment between Crow and Doyle is important because it shows the development of their friendship: Crow is sharing information about himself. But this information misrepresents a real sexual identity and draws inaccurate parallels between one’s sexuality and one’s gender.

The Angel of the Crows is not a novel about the main characters’ genders and sexualities. It’s a novel about the main characters’ friendship. And their friendship is genuinely delightful, in large part because Crow is not the misanthropic Holmes, but a character who giggles and is largely enjoyable to read. The friendship makes the novel, especially as the famous Sherlock Holmes mysteries may move the novel forward, but the mysteries themselves are not particularly interesting or engaging. A reader knows Crow and Doyle will find the culprit, just as a reader may know the outcome simply by familiarity with Conan Doyle’s original text. As with Addison’s previous novels, the world building and character relationships are the real story. It matters that Doyle tells Crow his birth name, the same way it matters that Crow tells Doyle he’s female: these are moments of vulnerability between the characters. I’ve focused on critiques of Addison’s treatment of gender and sexuality because, for all her world building, she did not do the necessary research. She is not able to speak responsibly to her audience, relying instead on misinformation and harmful narratives.

Works Cited

Addison, Katherine The Angel of the Crows. New York, Tor, 2020.

--“Queering Doctor Watson: Sexual Identity in The Angel of the Crows.” The Book Smuggler, 29 June 2020,

https://www.thebooksmugglers.com/2020/06/queering-dr-watson-sexual-identity-in-the-angel-of-the-crows.html

“Glossary of Terms – Transgender.” GLAAD, n.d. https://www.glaad.org/reference/transgender

Rowling, J.K. “J.K. Rowling Writes about Her Reasons for Speaking out on Sex and Gender Issues.” JKRowling.com, 10 June 2020,

https://www.jkrowling.com/opinions/j-k-rowling-writes-about-her-reasons-for-speaking-out-on-sex-and-gender-issues/

1888, London. A wounded army doctor returns home from Afghanistan and takes up with a brilliant but eccentric room-mate at 221 Baker Street. The promotional material for Katherine Addison’s The Angel of the Crows (2020) says it best from here: “This is not the story you think it is. These are not the characters you think they are.” This is a world populated with vampires and werewolves and angels, all living peacefully alongside humans. Enter Crow—our Sherlock figure—an angel—and Dr. J.H. Doyle—our Watson. The novel follows Crow and Doyle through a number of popular Sherlock Holmes mysteries, held together with the overarching plot to catch

Jack the Ripper. However, the truest part of Addison’s promotional material is this: “This is not the book you are expecting.” Fans of Addison’s The Goblin Emperor

(2014), will be sorely disappointed.

Addison is a master world builder. The Goblin Emperor is a rich fantasy with detailed histories of the monarchy, trade, and public works projects. Addison continues to rely on her strength of world building to craft the fantasy-scape London of The Angel of the Crows. There is an inherent logic to her worldbuilding, and she’s an expert at dispensing information without sounding expository. On the opening page of The Angel of the Crows, readers learn Doyle served in Afghanistan as part of Her Majesty’s Imperial Armed Forces Medical Corps—suggesting this is a world which readers are familiar with. But then, Doyle’s injury: “Two Afghani Fallen led the

charge [...] I should have died [...] and been torn apart by the Fallen’s monstrous claws” (11). These are Fallen angels, and this is Addison’s best use of fantasy, creating a living, breathable logic for her world. This is a world where the man who treats Doyle is famous for treating “spectral injuries” (11), a world where clairvoyance is taught to young girls. In this world, scientific forms of knowledge exist beyond our world’s rational sciences, in ways that are consistent, engaging, and surprising. However, The Angel of the Crows is poorly researched. Even accounting for some steam-punk and alternate history elements, the novel is clearly set in 1880s London. Addison is not able to balance the history of her novel’s era with a responsibility to her twenty-first century readers.

The most irresponsible parts of the novel are Addison’s treatment of Dr. Doyle’s gender, and the harmful narratives about gender and sexuality this novel perpetuates. Doyle can be read as a transgender man—a man assigned female at birth. Doyle dresses as a man, appears socially as a man, and is comfortable throughout the novel being referred to as a gentleman and with he/him pronouns. But Addison makes his gender purposefully ambiguous. In a write-up posted on The Book Smugglers, Addison writes:

You can read Doyle as a trans man, although that term is completely unavailable to the

characters, or you can read Doyle as a transvestite lesbian. Or you can read Doyle as

profoundly genderqueer (also a term not available to the characters) [...] I don’t want to

invalidate any of those readings.[...] I truthfully do not know how Doyle gender-

identifies. (“Queering Dr. Watson: Sexual Identity in The Angel of the Crows”)

Doyle is the first-person narrator of the novel and Addison does not know his gender. And while she is cognizant of the language gap between 1888 and today, she uses outdated language to describe him (if Doyle were a lesbian, perhaps she could find less offensive language to use in an article published in 2020?). In writing this novel, Addison did not do any research on gender or sexuality of the era, at least no research she shared publicly. In her Acknowledgements, Addison’s references are

The Annotated Sherlock Holmes, a list of books on Jack the Ripper, and a few additional sources on murders of the era. Due to her lack of research, Addison’s portrayal

of Doyle’s gender perpetuates a number of harmful narratives.

To start, Doyle’s sex assigned at birth comes as a mid-point plot device. Just before a major section break, Addison gives readers the titillating chapter title; “The Christian Names of Dr. Doyle”, as what the J.H. stood for in Doyle’s name was one of the biggest unsolved mysteries thus far (226). In this chapter, Doyle reveals to his love-interest, Miss Mary Morstan, that he cannot ask to marry her because “‘I am my father’s only daughter”’ (227). Doyle’s gender becomes a plot twist, the final piece of The Sign of the Four reimagining to be unraveled. His gender is not a meaningful exploration of this character’s struggles (or triumphs) with gender

and sexuality in the 1880s because Addison has not considered that line of research.

One of the most insidious problems of using transness as a plot device is that such a notion creates a narrative of trans suffering. When Doyle confesses that he was assigned female at birth to Miss Morstan, he apologizes to her. ‘“I’m sorry,’ I said, knowing full well it was inadequate” (228), suggesting his gender is a fault in his character, a hurt he has caused someone he loves. Miss Morstan then rejects him. “She turned sharply away from me [...] she said, in a voice that could not quite hold steady, ‘I think you had best leave”’ (228). Addison leaves no chance Doyle could be happy in love. In fact, his coming out (and subsequent rejection) becomes

a larger plot point to further the friendship between Crow and Doyle. For, if Doyle and Miss Morstan were to marry, Doyle would not be going on adventures with Crow. And so, rejected, Doyle returns to Baker street, gets drunk and confesses to Crow what happened. This scene works to solidify Crow as an ally to Doyle—the most important relationship either of them have. Yet, Doyle has no human allies who know about him being trans. The only person who doesn’t judge him for his sex assigned at birth is not a person at all. In bringing Crow and Doyle together as the principal relationship of the novel, Addison separates Doyle from loving

human relationships, further othering his gender and experience.

Addison is interested in masculinity as performance, and her novels are typically dominated by cisgender men, who explore masculinity outside of dominant narratives of violence. Yet, she presents Doyle’s gender as quite literal dress-up. After Miss Morstan rejects him, Doyle tells Crow about his struggles ‘“pretending

to be a man”’ (italics added 229). Then, towards the end of the novel, Doyle explains to another angel, ‘“I’ve masqueraded as a man far longer than I wore long skirts and corsets, and I don’t think I could go back. I certainly couldn’t go back to the gossip and embroidery that are a woman’s lot”’ (italics added 435). Pretend; masquerade. GLAAD (Gay and Lesbian Association Against Defamation), groups these words among a list of defamatory language to be avoided when discussing trans people (“Glossary of Terms – Transgender”). And yet Addison presents Doyle as a person who dresses up as a man to escape the difficulties of womanhood. Though Addison acknowledges that not all women amount solely to gossip and embroidery, Doyle still speaks with sexism against women: to be a woman is to have nothing in one’s life except small talk and small tasks. This narrative—that trans men are really women who only wants to escape sexism for male privilege—is a transphobic conversation happening right now with real consequences.

Addison isn’t the only fantasy writer to make uninformed comments about transgender people through her writing. In J.K. Rowling’s essay “J.K. Rowling Writes about Her Reasons for Speaking out on Sex and Gender Issues”—published the same month and year as The Angel of the Crows—Rowling is deeply concerned about “the huge explosion in young women wishing to transition [...] Some say they decided to transition after realising they were same-sex attracted, and that transitioning was partly driven by homophobia.” She goes on to say, “if I’d been born 30 years later, I too might have tried to transition. The allure of escaping womanhood would

have been huge.” (Rowling). Rowling’s fears—that trans men (in particular young trans men) are actually women wishing to escape sexism or homophobia—is paralleled in Addison’s portrayal of Doyle. To be clear, Addison’s treatment of Doyle is not a direct equivalent to the open transphobia of Rowling. However, Addison has a responsibility to be aware of what narratives her writing is pushing forwards.

Addison too, stumbles in her portrayal of sexuality. Crow’s sexuality is poorly researched and contributes to further misinformation for her audiences. Angels, as readers learn, are all female and only take on traditional gender presentations when humans give them a name and a habitation—dominion over a public building (Addison 240). Knowing Crow is also assigned female at birth (though we never really know how or if angels are technically born) provides a new layer of connection between him and Doyle, and does in fact add to Addison’s overarching argument that “Both Doyle and Crow are performing Victorian normative masculinity, but

neither one of them fits it” (“Queering Dr. Watson”). However, angels are also asexual— individuals who do not experience sexual attraction—and Addison makes false claims conflating sexuality and gender. When Crow explains to Doyle that all angels are female, he adds, ‘“Insofar as it makes sense to apply gender to asexual beings”’ (Addison 240). Except, asexuality is like any other sexual orientation: a person can be asexual and be any gender. This moment between Crow and Doyle is important because it shows the development of their friendship: Crow is sharing information about himself. But this information misrepresents a real sexual identity and draws inaccurate parallels between one’s sexuality and one’s gender.

The Angel of the Crows is not a novel about the main characters’ genders and sexualities. It’s a novel about the main characters’ friendship. And their friendship is genuinely delightful, in large part because Crow is not the misanthropic Holmes, but a character who giggles and is largely enjoyable to read. The friendship makes the novel, especially as the famous Sherlock Holmes mysteries may move the novel forward, but the mysteries themselves are not particularly interesting or engaging. A reader knows Crow and Doyle will find the culprit, just as a reader may know the outcome simply by familiarity with Conan Doyle’s original text. As with Addison’s previous novels, the world building and character relationships are the real story. It matters that Doyle tells Crow his birth name, the same way it matters that Crow tells Doyle he’s female: these are moments of vulnerability between the characters. I’ve focused on critiques of Addison’s treatment of gender and sexuality because, for all her world building, she did not do the necessary research. She is not able to speak responsibly to her audience, relying instead on misinformation and harmful narratives.

Works Cited

Addison, Katherine The Angel of the Crows. New York, Tor, 2020.

--“Queering Doctor Watson: Sexual Identity in The Angel of the Crows.” The Book Smuggler, 29 June 2020,

https://www.thebooksmugglers.com/2020/06/queering-dr-watson-sexual-identity-in-the-angel-of-the-crows.html

“Glossary of Terms – Transgender.” GLAAD, n.d. https://www.glaad.org/reference/transgender

Rowling, J.K. “J.K. Rowling Writes about Her Reasons for Speaking out on Sex and Gender Issues.” JKRowling.com, 10 June 2020,

https://www.jkrowling.com/opinions/j-k-rowling-writes-about-her-reasons-for-speaking-out-on-sex-and-gender-issues/

Chey Wollner's fiction and nonfiction appear in the anthologies Today, Tomorrow, Always; Hashtag Queer Vol. 3; and The Best of Loose Change Anthology, as well as additional print and online venues. Their short story "Girls Who Dance in the Flames" won Pulp Literature's 2018 Raven Short Story contest. They are pursuing their MFA in fiction at Florida Atlantic University where they are the managing editor of Swamp Ape Review. They are currently writing an alternate history novel about Bess and Harry Houdini.