The Evolution of Parasites by Emily Jaeger

Paperback: 48 pgs

Publisher: Sibling Rivalry Press (2016)

Purchase: @ Sibling Rivalry Press

Review by Travis Chi Wing Lau.

In 1980, Michel Serres published Le Parasite (The Parasite), which, as Steven D. Brown has noted, barely found an audience among British and North American scholars despite the text’s influence on thinkers like Deleuze and Guattari, who cite Serres repeatedly in their footnotes to A Thousand Plateaus (1988) and on Bruno Latour and the development of Actor-Network Theory.1 Serres’ text, which oscillates back and forth between theory and fable, science and literature, attempts to bridge the divide between the disciplines through an often uncomfortable, disorienting collision of discourses and ways of thinking. Yet, the thesis of The Parasite is deceptively simple: the central model for thinking about society and culture is the relationship between parasite and host. For Serres, such domains are defined by an intrinsic exploitation, a “primordial, one-way, and irreversible relation that is the base of human institutions and disciplines: society, economy, and work; human sciences and hard sciences; religion and history. All of these have the parasitic relation as their basic and fundamental component.”2 Serres plays with the multiple meanings of “parasite” in French: a biological microbe that consumes (and even kills) its host, a guest that exchanges his company for food and drink, and static or interference in a system. The figure of the parasite is polysemic, polymorphic.

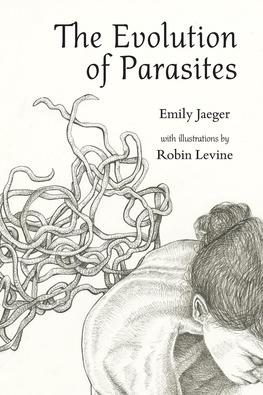

In my reading of Jaeger’s volume, I could not help but recall the unforgiving experience many years ago of engaging for the first time with Serres’ text, which “in a profound sense, struggles against clarity, which is to say that it struggles in a way, against language itself, (mis)understood as the more or less transparent and unproblematic transmission of conceptual and analytical content from writer to reader.”3 This frictional relationship to language and meaning seems to be precisely the project of poetry, and particularly of Jaeger’s work, which persistently puts into tension the visual and the textual through its inclusion of illustrations by Robin Levine. These surrealist images of bodies and objects penetrated by worms and larvae face the text of the poems on the opposite page. As readers, we are left to navigate these two forms that feed upon one another—neither one a means by which we can apprehend the other in any full or complete way. We cannot reduce any one of them to paratext, to mere supplement—they are symbiotic.

Parasites, as both Serres and Jaeger remind us, are seemingly minor actors whose acts engender profound effects on their hosts. The roundworm that opens the volume, while easily flushed away, “knows every part” of the speaker: “Born in your stomach, hiked the streets / of your veins, slept between the breaths in your lungs, coughed up then / swallowed down.” The dynamic between the speaker and the parasite is simultaneously one of power (the speaker “flush[es] the fucker down”) but also intimacy. In the case of the roundworm, it is simultaneously host and guest, as it traverses and becomes the landscape of the speaker’s body. We witness this same perverse intimacy in “The Sand Flea,” in which the speaker details the “tear[ing] / into life” of a flea “between the skin and meat / of my toes.” These gothic scenes, both disgusting and fascinating, between human and non-human burst with life despite their minimalism—an embodiment of the parasite in verse form further animated by Levine’s visceral drawing style.

The “evolution” in the collection’s title signals the shifting types of parasites that appear throughout the volume and the unique nature of their parasitism. Jaeger underscores throughout the volume how the parasite has access to the most intimate of spaces—a deep invasion that is unwarranted, unannounced, unexpected. In the title poem, vignettes accompany what read like textbook references to different parasitic sea snails and their methods of parasitism. These vignettes capture the experiences of the speaker and a number of other women, including a graphic scene of rape of a Muslim woman named Raya. Jaeger reveals in her notes that the italicized portions about sea snails are quoted directly from The Art of Being a Parasite by Claude Combes, who “analyzes the evolution of parasitic species from non-parasitic species, the perspective of the host, different examples of parasitic and/or symbiotic relationships and mating patterns.” She notes how Combes frequently employs a master to slave relationship to describe parasitic relation. This rhetoric and imagery directly parallel her vignettes about sexual predation and violence—yet again symbiotic.

Through her notes, Jaeger outlines a parasitic method of extracting and interjecting excerpts of found texts to create the bodies of her poems. She uses this to grapple with another violent form of parasitism: colonialism. “The Sand Flea” repurposes found text from Francisco López de Gómara’s Historia General de Las Indias, an “armchair” encyclopedia of botany and peoples encountered by Columbus and his men. Having never been to the Americas himself, Gómara relied, like many other colonial writers, on travel narratives and received oral accounts of voyages throughout the New World. Jaeger reveals how the colonial imaginary was as parasitic as its practices. In accord with Serres’ thesis, settler colonialism, still alive and well, is but another manifestation of the parasitic logics that define Western modernity and whose consequences have been dislocation and dispossession: only take, never give. Far from being able to “flush the fucker down” anymore, these later poems linger in the traumatic aftermath of a parasitic encounter that cannot be so easily purged, be it through faith or forgetting.

And what are we, as readers, but parasites ourselves? We come to the text to consume it, to take from it what we will and leave. Jaeger plants, with a reminder that we are not exempt from this parasitical relation writhing at the heart of who we are and the lives we live.

1See “Science, Translation, and the Logic of the Parasite.” Theory, Culture & Society. 19.3 (2002): 1—27.

2Michel Serres. The Parasite. Trans. Lawrence R. Schehr. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007. x.

3Cary Wolfe. “Bring the Noise: The Parasite and the Multiple Genealogies of Posthumanism.” Introduction to the 2007 edition of The Parasite. Trans. Lawrence R. Schehr. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007. xiii.

Emily Jaeger is a writer and editor living in the New York area. Emily previously served in the Peace Corps for two years as an agricultural extensionist in Paraguay, teaching local farmers sustainable growing practices and leading community development projects. Currently a matriculating MFA student at UMASS Boston, she is co-editor and co-founder of the Window Cat Press, a magazine for emerging writers, a features editor for Woven Tale Press, and a book reviewer and reader for Salamander Magazine.

Emily is the author of the chapbook, The Evolution of Parasites (Sibling Rivalry Press), illustrated by Robin Levine. Her work has been publishing in The Offing, Four Way Review, TriQuarterly, and Apt among others. Emily has received fellowships as a Literary Lambda Emerging Writer, a participant in TENT, and the New York State Summer Writers Institute. Her poem, "Palmyra's Arch of Triumph" won an Academy of American Poet's Prize.