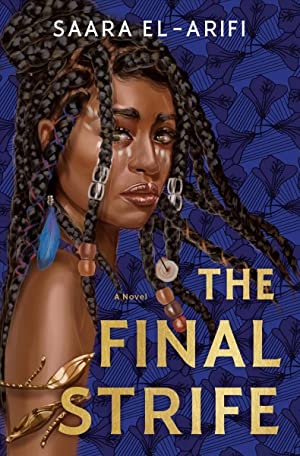

The Final Strife by Saara El-Arifi

The Final Strife by Saara El-Arifi

Hardcover: 608 pages

Publisher: Del Rey, 2022

Purchase @ Penguin Random House

Hardcover: 608 pages

Publisher: Del Rey, 2022

Purchase @ Penguin Random House

The blood, the power, the life: Review by Ashura Lewis

For those bibliophiles who have been waiting for a new twist on an old world, the wait is finally over. Saara El-Arifi’s debut novel, The Final Strife, lives up to the excitement and anticipation surrounding the six-figure, five-way auction that led to Harper Voyager acquiring the UK/Commonwealth publication rights. In much of Western literature, when novel plots venture into the realms of historical racism, slavery, and cultural oppression they risk becoming little more than historical fiction or, worse, it becomes bad historical fiction. Thankfully, El-Arifi avoids these pitfalls. All the inhabitants of her world are dark skinned along a color spectrum that aligns with African and Middle Eastern ethnicities. However, in the world of The Final Strife, the source of divisiveness does not rely on the color of one’s skin but instead the color of one’s blood.

Saara El-Arifi provides The Final Strife as the beginning of an African/Arabian fantasy trilogy. This culturally blended departure from mainstream Western fantasy adds a rich layer of realism to an otherwise alien and fantastic world. It is likely that El-Arifi was able to pull from her own experiences of walking between two or more cultures as a child of a Ghanaian/British mother and a Sudanese/Arab father. Her heritage has also been evident in the themes of her stories, and her debut novel is no different. Raised in the Middle East before a move to Sheffield, Yorkshire, El-Arifi is no stranger to navigating worlds where an “otherness” dominates all interactions. The references to both the American and Arab slave trade as well as themes based on navigating two worlds reflects El-Arifi’s unique background and provides readers with a fresh point of view for fantasy.

Set in an unknown world after the great “Ending Fire” that destroyed most of the world and its inhabitants, the Marion Sea surrounds the Warden’s Empire, the last bastion of civilization. Structured around a rigid caste system worthy of A Handmaid’s Tale, society separates into three classes/types of people: the Embers, the Dusters, and the Ghostings. Each group is defined by the color of their blood. Embers, the highest caste, bleed red. Dusters, the middle caste, bleed blue, and the lowest caste, the Ghostings, bleed clear. El-Arifi’s treatment of the caste system is recognizable as a reimagining of plantation life during the era of slavery. “If the Warden’s Empire were an orchard, the Embers would be the fruit at the top. Red and ripe, most revered… The Dusters, we’d be the fallen apples, bruised blue… The Ghostings, like their translucent blood, they cannot be seen, they are down below… but essential to the Empire” (p. 55). Embers are full citizens who control all aspects of life and culture including the justice, education, and political systems of the land. On the other end of the spectrum, Ghostings are barely recognized as people. They serve as silent servants within Ember households. The emphasis here is on “silent” as all Ghostings are mutilated as babies by having their tongues cut out and their hands cut off. The Dusters walk a narrow path between the two extreme states of living providing the economic labor force that allows for trade and stability within the Empire.

The Final Strife is a story of three women who discover who they are as they move through a system of casual violence and unthinking cruelty. Whether facing the Aktibar, an official proving ground and series of tests that liken to the Tangata manu or Birdman Races of Easter Island in terms of difficulty, or the underground fighting rings of the Warden of Crime run by a man called Loot who definitely gives off Don Corleone and King Pin vibes, attempts to improve one’s station or finance requires both violence and blood, no matter the color. Even the magic of the world requires the liquid life sacrifice. Embers are known for their ability to perform magical works through blood rune writing and manipulation. As the name implies, blood work requires blood to make it work and only red blood is known to be up to the task. Indeed, everything in the Warden Empire comes down to “the blood, the power, the life” (p. 138).

The depth of degradation and oppression permeates every aspect of the cultures found within the Empire, from the secret sign language of the Ghostings to the colloquial greeting of “how’s it hurting?” used in Duster and Ghosting interactions. Each chapter begins with a quote or excerpt from poetry, prayers, or other sacred text. Each entry is laden with propaganda differing only in the source and ambition of the statements. Readers learn early that “severing the hands and tongues of Ghostings benefits their well-being. Those whose wounds fester are weeded out young, their frail countenance discarded before they become a nuisance to their masters” (p. 26). That such proclamations are reminiscent of statements made by slave holders in defense of slavery is no coincidence. El-Arifi does not pull her punches in establishing exactly how the Embers view those they, in all but name, enslave. And it is within this restrictive society that readers are introduced to the three women driving the book’s plot.

Sylah lives among the Dusters in the Dredge, but we soon learn she has a secret that connects her with the Sandstorm, a group working to bring down the Wardens and end the systemic oppression of Dusters and Ghostings. Sylah was raised in the teachings and trainings of the Sandstorm and had become a powerful fighter, but after her family is killed in front of her, she loses her will to continue the resistance. To make matters worse, Sylah is dependent on joba seeds, an addictive opioid type drug whose frequent use leads to brain damage and death. Though obviously functioning as the novel’s main protagonist, Sylah’s addiction is a Holmesian struggle against the press of the outside world. Sylah uses the joba seeds as her escape from a cruel reality, but even the most potent drug can only provide a temporary solace as Sylah soon learns.

Anoor is the daughter of the Warden of Strength and, as such, has led a privileged life high in Ember society. It is expected that she will follow in her incomparable mother’s footsteps, but Anoor lacks more than just the will to succeed as her future too is caught up in and dependent upon the machinations of the Sandstorm. As an Ember, Anoor is trained in the Blood Magic, but her blood holds a secret that could destroy her and everything around her. This secret is also a constant source of shame and ammunition for the emotional abuse inflicted by her mother.

And then there’s Hassa, the Ghosting friend of Sylah. Hassa is the shadow that follows all the characters, sometimes to support them, sometimes to acquire information on them. As a Ghosting, she has access to Ember society and into their intimate spaces. Much like the house slave on the plantation, her presence is often forgotten, and her abilities are always underestimated especially when considering her disabilities. Despite being effectively hobbled as an infant, Hassa becomes the foundational protagonist upon which the other women rely. But El-Arifi does not fall into tropes of the “super crip.” Instead, she functionally ignores the perceived impairment among Ghostings, treating their disfigurement as simply another manifestation of what the human form can look like. Tools, clothing, and other modifications enable Ghostings, like Hassa, to operate physically in society with the ease of an Ember or Duster.

And then there is the fourth and final major player in the Empire, the Tidewind. Each day a brutal wind roars through the entire settlement/city, its razor-sharp blue dust scoring stone, stripping paint, and flaying any flesh it touches. It is in this environmentally and politically hostile landscape that The Final Strife takes place. Then again, is it really the final strife?

El-Arifi creates a fantasy world that deals with emotionally abusive mothers, disability and impairments, and drug addiction in ways that are fresh and full of potential energy. While more subtle in character opposition than the full throttle rebellion of the Hunger Games, through Sylah, Anoor, and Hassa, El-Arifi immerses readers in her trilogy’s first steps toward revolution. Though entitled The Final Strife it is all too clear that there is far more to come as readers become one of the Sandstorm and join El-Arifi’s trio in the resistance.

For those bibliophiles who have been waiting for a new twist on an old world, the wait is finally over. Saara El-Arifi’s debut novel, The Final Strife, lives up to the excitement and anticipation surrounding the six-figure, five-way auction that led to Harper Voyager acquiring the UK/Commonwealth publication rights. In much of Western literature, when novel plots venture into the realms of historical racism, slavery, and cultural oppression they risk becoming little more than historical fiction or, worse, it becomes bad historical fiction. Thankfully, El-Arifi avoids these pitfalls. All the inhabitants of her world are dark skinned along a color spectrum that aligns with African and Middle Eastern ethnicities. However, in the world of The Final Strife, the source of divisiveness does not rely on the color of one’s skin but instead the color of one’s blood.

Saara El-Arifi provides The Final Strife as the beginning of an African/Arabian fantasy trilogy. This culturally blended departure from mainstream Western fantasy adds a rich layer of realism to an otherwise alien and fantastic world. It is likely that El-Arifi was able to pull from her own experiences of walking between two or more cultures as a child of a Ghanaian/British mother and a Sudanese/Arab father. Her heritage has also been evident in the themes of her stories, and her debut novel is no different. Raised in the Middle East before a move to Sheffield, Yorkshire, El-Arifi is no stranger to navigating worlds where an “otherness” dominates all interactions. The references to both the American and Arab slave trade as well as themes based on navigating two worlds reflects El-Arifi’s unique background and provides readers with a fresh point of view for fantasy.

Set in an unknown world after the great “Ending Fire” that destroyed most of the world and its inhabitants, the Marion Sea surrounds the Warden’s Empire, the last bastion of civilization. Structured around a rigid caste system worthy of A Handmaid’s Tale, society separates into three classes/types of people: the Embers, the Dusters, and the Ghostings. Each group is defined by the color of their blood. Embers, the highest caste, bleed red. Dusters, the middle caste, bleed blue, and the lowest caste, the Ghostings, bleed clear. El-Arifi’s treatment of the caste system is recognizable as a reimagining of plantation life during the era of slavery. “If the Warden’s Empire were an orchard, the Embers would be the fruit at the top. Red and ripe, most revered… The Dusters, we’d be the fallen apples, bruised blue… The Ghostings, like their translucent blood, they cannot be seen, they are down below… but essential to the Empire” (p. 55). Embers are full citizens who control all aspects of life and culture including the justice, education, and political systems of the land. On the other end of the spectrum, Ghostings are barely recognized as people. They serve as silent servants within Ember households. The emphasis here is on “silent” as all Ghostings are mutilated as babies by having their tongues cut out and their hands cut off. The Dusters walk a narrow path between the two extreme states of living providing the economic labor force that allows for trade and stability within the Empire.

The Final Strife is a story of three women who discover who they are as they move through a system of casual violence and unthinking cruelty. Whether facing the Aktibar, an official proving ground and series of tests that liken to the Tangata manu or Birdman Races of Easter Island in terms of difficulty, or the underground fighting rings of the Warden of Crime run by a man called Loot who definitely gives off Don Corleone and King Pin vibes, attempts to improve one’s station or finance requires both violence and blood, no matter the color. Even the magic of the world requires the liquid life sacrifice. Embers are known for their ability to perform magical works through blood rune writing and manipulation. As the name implies, blood work requires blood to make it work and only red blood is known to be up to the task. Indeed, everything in the Warden Empire comes down to “the blood, the power, the life” (p. 138).

The depth of degradation and oppression permeates every aspect of the cultures found within the Empire, from the secret sign language of the Ghostings to the colloquial greeting of “how’s it hurting?” used in Duster and Ghosting interactions. Each chapter begins with a quote or excerpt from poetry, prayers, or other sacred text. Each entry is laden with propaganda differing only in the source and ambition of the statements. Readers learn early that “severing the hands and tongues of Ghostings benefits their well-being. Those whose wounds fester are weeded out young, their frail countenance discarded before they become a nuisance to their masters” (p. 26). That such proclamations are reminiscent of statements made by slave holders in defense of slavery is no coincidence. El-Arifi does not pull her punches in establishing exactly how the Embers view those they, in all but name, enslave. And it is within this restrictive society that readers are introduced to the three women driving the book’s plot.

Sylah lives among the Dusters in the Dredge, but we soon learn she has a secret that connects her with the Sandstorm, a group working to bring down the Wardens and end the systemic oppression of Dusters and Ghostings. Sylah was raised in the teachings and trainings of the Sandstorm and had become a powerful fighter, but after her family is killed in front of her, she loses her will to continue the resistance. To make matters worse, Sylah is dependent on joba seeds, an addictive opioid type drug whose frequent use leads to brain damage and death. Though obviously functioning as the novel’s main protagonist, Sylah’s addiction is a Holmesian struggle against the press of the outside world. Sylah uses the joba seeds as her escape from a cruel reality, but even the most potent drug can only provide a temporary solace as Sylah soon learns.

Anoor is the daughter of the Warden of Strength and, as such, has led a privileged life high in Ember society. It is expected that she will follow in her incomparable mother’s footsteps, but Anoor lacks more than just the will to succeed as her future too is caught up in and dependent upon the machinations of the Sandstorm. As an Ember, Anoor is trained in the Blood Magic, but her blood holds a secret that could destroy her and everything around her. This secret is also a constant source of shame and ammunition for the emotional abuse inflicted by her mother.

And then there’s Hassa, the Ghosting friend of Sylah. Hassa is the shadow that follows all the characters, sometimes to support them, sometimes to acquire information on them. As a Ghosting, she has access to Ember society and into their intimate spaces. Much like the house slave on the plantation, her presence is often forgotten, and her abilities are always underestimated especially when considering her disabilities. Despite being effectively hobbled as an infant, Hassa becomes the foundational protagonist upon which the other women rely. But El-Arifi does not fall into tropes of the “super crip.” Instead, she functionally ignores the perceived impairment among Ghostings, treating their disfigurement as simply another manifestation of what the human form can look like. Tools, clothing, and other modifications enable Ghostings, like Hassa, to operate physically in society with the ease of an Ember or Duster.

And then there is the fourth and final major player in the Empire, the Tidewind. Each day a brutal wind roars through the entire settlement/city, its razor-sharp blue dust scoring stone, stripping paint, and flaying any flesh it touches. It is in this environmentally and politically hostile landscape that The Final Strife takes place. Then again, is it really the final strife?

El-Arifi creates a fantasy world that deals with emotionally abusive mothers, disability and impairments, and drug addiction in ways that are fresh and full of potential energy. While more subtle in character opposition than the full throttle rebellion of the Hunger Games, through Sylah, Anoor, and Hassa, El-Arifi immerses readers in her trilogy’s first steps toward revolution. Though entitled The Final Strife it is all too clear that there is far more to come as readers become one of the Sandstorm and join El-Arifi’s trio in the resistance.

Ashura Lewis is a PhD student at the University of Southern Mississippi. A native of Jackson, Mississippi, Ashura taught high school English and Creative Writing in both Louisiana and Mississippi public school districts for nearly a decade. In recent years, she has worked with social justice non-profits as both a grant writer and communications specialist. Ashura earned her B.S degree in Psychology from Jackson State University, her J.D. degree from Mississippi College School of Law, and her M.A. degree in English Literature from Jackson State University. She is also a published author and editor of fiction and nonfiction works.