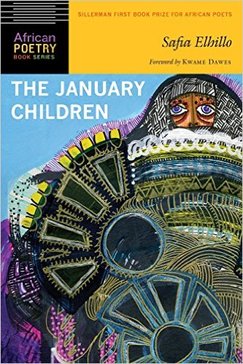

The January Children by Safia Elhillo

Paperback: 63 pages

Publisher: University of Nebraska Press

Purchase: @ University of Nebraska Press

Reviewed by Margaret Stawowy.

I first heard about The January Children in a Bustle article “15 of the Most Anticipated Poetry Collections of 2017” by C. E. Miller. Sudanese-American poet Safia Elhillo was also featured on one of my favorite poetry websites: Split this Rock where she is a Teaching Artist.

In addition, I have developed a fascination with Sudan after reading the Dave Eggers book What Is the What, though Elhillo presents another view of Sudan than the one presented in that autobiographical novel: northern instead of southern (Southern Sudan became a separate nation in 2011), female, not male, and Islamic, not Christian/indigenous.

What remains the same are tumultuous historical events that forced a generation of “January children” to leave their country on both sides of the nation. The title January Children derives from a practice of British occupiers, (and later, U.S. immigration officials), who assigned a birth date of January 1, and a birth year according to height, in a country where birthdays had not been recorded.

I had to read this book.

Elhillo has created a collection of poetry that straddles the many divisions of her life: English/Arabic, African/North American, and past/present, but also, the politics of gender, race, and geography.

Throughout she explores the linguistic influence of Arabic, a language that is not fully hers due to her emigration, though it deeply permeates her thought. Some poems are difficult to quote due to embedded Arabic writing that nonetheless create a pleasing contrast to the lines in which they appear.

A further comment regarding Arabic is found in the erasure poem (the title of the poem is the same as the textbook from which it was extracted) “Sudan Today. Nairobi: University of Africa, 1971. Print.”

Note on Arabic

It is difficult.

The publishers do not pretend

to have solved this problem.

In this and other poems, the reader feels her longing for a language that lives within her, yet often eludes her recall. Her neurology is wired to an Arabic experience, but the words sometimes (frustratingly!) go missing. This book is a kind of solution to her problem of expressing just what has vaporized.

There is great variety in the form that these poems assume upon the page from left-justified stanzas, to blocks of words, to solid paragraphs with spaces in lieu of the kind of stops that are signified through punctuation. There is lack of capitalization and liberal use of ampersands, italics and indentations. There is even an Arabic/romanized glossary presented in a tabular format. The lack of composition and grammar “rules” suits the narrative of the book, which embodies the shiftless position in which a woman between cultures experiences.

Elhillo is an engaging storyteller. In a series of poems partly based in her imagination, she chronicles her relationship with the iconic (now deceased) Egyptian Arabic musician Abdelhalim Hafez. This handsome, passionate singer known as the Dark-Skinned Nightingale confers a kind of cultural and emotional acceptance that Elhillo so desires: to be recognized for the uniqueness of her ethnic experience, to be recognized as Arabic, and furthermore, to not be diminished because of her gender, dark skin, or lively hair. Hafez sings of a brown-skinned girl with whom he is enamored, in a culture that prizes fair skin. Elhillo very much wants to be that woman. She attends a series of interviews to be Hafez’s girl, is seemingly accepted, then rejected. But as the series continues interspersed with other autobiographical poems, the Hafez poems act as a vehicle for Elhillo to explore identity, events, and observations from her own life—even when the title of the poem suggests otherwise. From “watching arab idol with abdelhalim hafez”:

i open my mouth a man in a cairo shop

tells me I look too clean to be from sudan

waits for me to thank him lebanese singer ragheb alama

is my least favorite judge on arab idol

i watch every week as the brownest

are first to leave. . .

and

when ragheb alama says sudanese women

are the ugliest in the world i am afraid

that i believe him. . .

Elhillo’s extended family, well-meaning and loving, are firmly rooted in traditional Sudan, and can’t understand her Western ways. They can only offer her half-acceptance. “self portrait with dirty hair” strikingly spells out this predicament:

trying to flatten the jagged curl i hear my great-grandmother she’s a

pretty girl but why do you let her go outside like that people will

think she does not have a name i hear my grandmother trying to

explain away all my knots her mother took her to America it is

different she does not know anymore how to look done. . .”

In Sudan, she is considered too black; in America, not black enough to be truly “black.” In Sudan, she speaks accented Arabic; in America, accented English. She longs for Sudan, but a pre-war Sudan that no longer exists. Then there is the reality of America embedded with violence and racism where she will never quite feel like an insider. She longs for a country in which she is recognized as fully herself. She “breaks up” with Abdelhalim only to be left with American boys at parties who are attracted to her exotic beauty, not understanding her cultural complexity:

. . .what if I do not want to go home at all let alone with you

let alone [i got a girl from the land of milk & honey] [you’re so beautiful may I ask]

[okay but mixed with what] [but if you’re from africa how come] . . .

Yet Elhillo accepts, even embraces her situation with insight and comedy. When discussing her parents, particularly her father (whom her mother left) she creates a universe in which her parents’ love could blossom and thrive. So she describes an invented romantic and vibrant evening in which her parents did not meet. She speaks of a father who loved his wife so much that for every stick of gum chewed, he saved half for his beloved, who put it in a jar as a kind of quirky romantic momento. The reader, like Elhillo, feels a protective kinship with this unknown man “. . .so lively and handsome/that only bad magic could have emptied/& filled him with smoke.” She recognizes that before her parents were parents, they were just two young people, untried and innocent.

Together, Elhillo, her extended family, Hafez, the Sudanese, and Americans all become citizens in an imagined, off-kilter, sometimes violent, yet comic, and resonant world. Elhillo writes with mastery and unapologetic honesty, tempered with compassion and sagacity.

Publisher: University of Nebraska Press

Purchase: @ University of Nebraska Press

Reviewed by Margaret Stawowy.

I first heard about The January Children in a Bustle article “15 of the Most Anticipated Poetry Collections of 2017” by C. E. Miller. Sudanese-American poet Safia Elhillo was also featured on one of my favorite poetry websites: Split this Rock where she is a Teaching Artist.

In addition, I have developed a fascination with Sudan after reading the Dave Eggers book What Is the What, though Elhillo presents another view of Sudan than the one presented in that autobiographical novel: northern instead of southern (Southern Sudan became a separate nation in 2011), female, not male, and Islamic, not Christian/indigenous.

What remains the same are tumultuous historical events that forced a generation of “January children” to leave their country on both sides of the nation. The title January Children derives from a practice of British occupiers, (and later, U.S. immigration officials), who assigned a birth date of January 1, and a birth year according to height, in a country where birthdays had not been recorded.

I had to read this book.

Elhillo has created a collection of poetry that straddles the many divisions of her life: English/Arabic, African/North American, and past/present, but also, the politics of gender, race, and geography.

Throughout she explores the linguistic influence of Arabic, a language that is not fully hers due to her emigration, though it deeply permeates her thought. Some poems are difficult to quote due to embedded Arabic writing that nonetheless create a pleasing contrast to the lines in which they appear.

A further comment regarding Arabic is found in the erasure poem (the title of the poem is the same as the textbook from which it was extracted) “Sudan Today. Nairobi: University of Africa, 1971. Print.”

Note on Arabic

It is difficult.

The publishers do not pretend

to have solved this problem.

In this and other poems, the reader feels her longing for a language that lives within her, yet often eludes her recall. Her neurology is wired to an Arabic experience, but the words sometimes (frustratingly!) go missing. This book is a kind of solution to her problem of expressing just what has vaporized.

There is great variety in the form that these poems assume upon the page from left-justified stanzas, to blocks of words, to solid paragraphs with spaces in lieu of the kind of stops that are signified through punctuation. There is lack of capitalization and liberal use of ampersands, italics and indentations. There is even an Arabic/romanized glossary presented in a tabular format. The lack of composition and grammar “rules” suits the narrative of the book, which embodies the shiftless position in which a woman between cultures experiences.

Elhillo is an engaging storyteller. In a series of poems partly based in her imagination, she chronicles her relationship with the iconic (now deceased) Egyptian Arabic musician Abdelhalim Hafez. This handsome, passionate singer known as the Dark-Skinned Nightingale confers a kind of cultural and emotional acceptance that Elhillo so desires: to be recognized for the uniqueness of her ethnic experience, to be recognized as Arabic, and furthermore, to not be diminished because of her gender, dark skin, or lively hair. Hafez sings of a brown-skinned girl with whom he is enamored, in a culture that prizes fair skin. Elhillo very much wants to be that woman. She attends a series of interviews to be Hafez’s girl, is seemingly accepted, then rejected. But as the series continues interspersed with other autobiographical poems, the Hafez poems act as a vehicle for Elhillo to explore identity, events, and observations from her own life—even when the title of the poem suggests otherwise. From “watching arab idol with abdelhalim hafez”:

i open my mouth a man in a cairo shop

tells me I look too clean to be from sudan

waits for me to thank him lebanese singer ragheb alama

is my least favorite judge on arab idol

i watch every week as the brownest

are first to leave. . .

and

when ragheb alama says sudanese women

are the ugliest in the world i am afraid

that i believe him. . .

Elhillo’s extended family, well-meaning and loving, are firmly rooted in traditional Sudan, and can’t understand her Western ways. They can only offer her half-acceptance. “self portrait with dirty hair” strikingly spells out this predicament:

trying to flatten the jagged curl i hear my great-grandmother she’s a

pretty girl but why do you let her go outside like that people will

think she does not have a name i hear my grandmother trying to

explain away all my knots her mother took her to America it is

different she does not know anymore how to look done. . .”

In Sudan, she is considered too black; in America, not black enough to be truly “black.” In Sudan, she speaks accented Arabic; in America, accented English. She longs for Sudan, but a pre-war Sudan that no longer exists. Then there is the reality of America embedded with violence and racism where she will never quite feel like an insider. She longs for a country in which she is recognized as fully herself. She “breaks up” with Abdelhalim only to be left with American boys at parties who are attracted to her exotic beauty, not understanding her cultural complexity:

. . .what if I do not want to go home at all let alone with you

let alone [i got a girl from the land of milk & honey] [you’re so beautiful may I ask]

[okay but mixed with what] [but if you’re from africa how come] . . .

Yet Elhillo accepts, even embraces her situation with insight and comedy. When discussing her parents, particularly her father (whom her mother left) she creates a universe in which her parents’ love could blossom and thrive. So she describes an invented romantic and vibrant evening in which her parents did not meet. She speaks of a father who loved his wife so much that for every stick of gum chewed, he saved half for his beloved, who put it in a jar as a kind of quirky romantic momento. The reader, like Elhillo, feels a protective kinship with this unknown man “. . .so lively and handsome/that only bad magic could have emptied/& filled him with smoke.” She recognizes that before her parents were parents, they were just two young people, untried and innocent.

Together, Elhillo, her extended family, Hafez, the Sudanese, and Americans all become citizens in an imagined, off-kilter, sometimes violent, yet comic, and resonant world. Elhillo writes with mastery and unapologetic honesty, tempered with compassion and sagacity.

Safia Elhillo is the author of The January Children (University of Nebraska Press, 2017).

Sudanese by way of Washington, DC, she received a BA from NYU’s Gallatin School of Individualized Study and an MFA in poetry at the New School. Safia is a Pushcart Prize nominee, co-winner of the 2015 Brunel University African Poetry Prize, and winner of the 2016 Sillerman First Book Prize for African Poets. She has received fellowships from Cave Canem, The Conversation, and Crescendo Literary and The Poetry Foundation’s Poetry Incubator. In addition to appearing in several journals and anthologies including “The BreakBeat Poets: New American Poetry in the Age of Hip-Hop,” her work has been translated into Arabic, Japanese, Estonian, and Greek. With Fatimah Asghar, she is co-editor of the anthology “Halal If You Hear Me.”