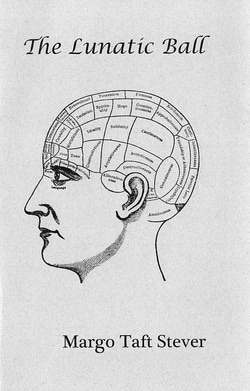

The Lunatic Ball by Margo Taft Stever

Chapbook: 26 pages

Publisher: Kattywompus Press (2015)

Purchase: @ Kattywompus Press

Review by Laura Madeline Wiseman

In Margo Taft Stever’s newest collection The Lunatic Ball, she explores madness in the 1900s and the ways in which we cared for mentally ill, by doctors, by asylums, and by throwing them lunatic balls. Part meditation of possible medically-induced madness and part exploration of misplaced family history, Stever’s collection turns on four found poems from letters sent by her great-grandfather to his father and letters sent from the superintendent home on the care received in the Cincinnati Sanitarium, a private hospital for the insane. In the found poem “Cracked Piano,” Peter Rawson Taft, who was William Howard Taft’s half-brother, writes home to his father, Alphonso Taft, who was attorney general in the Grant administration and secretary of war. Peter describes the other patients who laugh, remain silent, or grunt, and who all sit at a table where “The conversation is neither amusing/ nor instructive” (4). He also describes the conditions of the Cincinnati hospital, a place where,

Each patient has a separate

room with a carpet,

a bed, a table, a wash-stand,

a box, and one chair,

but no gas and no candles. (3)

Peter’s letter is preoccupied with the place in which he resides that he calls plain and hard, how lonely he is, and how he longs for visitors. In the other found poem, “No Occurrence of an Exciting Nature” from Peter’s letter, he writes of card games with other patients and of the lack of letters he’s received from friends or family, suggesting that he’s been forgotten during the time he’s been stowed away. What makes his letters provocative is the way Stever attends to the missed opportunity and wasted life of her ancestor, mostly forgotten by the historical record, but one The Lunatic Ball stands to correct. Her great-grandfather’s insanity may have been instigated by taking the prescribed medicine of the day. Peter studied classics at Yale, but a few months before graduation, he came down with Typhoid fever. He was given Calomel, a mercury containing drug. He survived the fever, but suffered from reoccurring headaches thereafter and was hospitalized, a placement that silenced family discourse about the unfortunate relative’s condition and eclipsed from the William Howard Taft Papers. It was only during Stever’s research for the book William Howard Taft and the 1905 U.S. Diplomatic Mission to Asia (Zhejiang University Press, 2012; English-language edition, 2015) that she uncovered the letters and her curiosity to explore such treatment of mental illness became the subject of her chapbook The Lunatic Ball.

The chapbook also contains poems that ruminate on representative treatment of the insane. The title poem explores the phenomena of lunatic balls, which were balls for those in such hospitals that allowed for “non-insane” people to watch, much like one might watch the proceedings of a trial or a congressional debate, but with music, food, dancing, and beverages being consumed. The poem opens with the evocative image of madmen cavorting,

Furious dancing gives way to screams;

five men stare, ghoulish, at the wall.

This is the lunatic ball. (6)

This exphrasis poem that responds to George Bellows’ painting “Dance in a Madhouse” presents both maddening displays of behavior while it simultaneously humanizes the individuals, pointing to the likely causes of mental illness like Calomel, women who were locked up when they sought separation from their husbands before divorce was a woman’s right, and fevers that brought on brain trauma. Stever also does something more. She gives us not just causation, but also intellectualizes the mad. She gives them smarts, self-awareness, and acuity about their situation, suggesting that such balls and hospitalizations did more to make women and men mad than any other explanatory experiences. She writes,

Behind a glass wall, well-dressed spectators, riveted,

sit amused. Looking at them looking, the patients

know they are through. (6)

Lunatic balls were considered humanitarian treatment even as they worked to reinscribe the separation between the mad and non-mad—the actors and voyeurs, dancers and watchers, sane and insane. Rather than viewing madness as a state of degradations along a vast line, the act of inviting some members of the society to see others as insane likely did more to make madness real than any dose of mercury.

Other poems in The Lunatic Ball meditate on variations of madness—the desire to be thin contrasted with the desire to eat comfort foods (“Animal Crackers”), women who dress as men to enable them to make art (“Horse Fair”), artists like Van Gogh who felt his phantom ear after it had been sliced off (“Van Gogh to His Mistress”), pickpockets, passerby of nunneries, animals who murder, the weirdness of the body. These are rich, evocative poems, poems that reflect on what madness meant in the late 1800s and what madness means today, nearly one hundred and fifty years later. In finely crafted poems, musical, lyric, and precise, Stever suggests inThe Lunatic Ball that we’re all spectators and dancers and the difficulty is knowing which side of viewing wall we’re on.

Chapbook: 26 pages

Publisher: Kattywompus Press (2015)

Purchase: @ Kattywompus Press

Review by Laura Madeline Wiseman

In Margo Taft Stever’s newest collection The Lunatic Ball, she explores madness in the 1900s and the ways in which we cared for mentally ill, by doctors, by asylums, and by throwing them lunatic balls. Part meditation of possible medically-induced madness and part exploration of misplaced family history, Stever’s collection turns on four found poems from letters sent by her great-grandfather to his father and letters sent from the superintendent home on the care received in the Cincinnati Sanitarium, a private hospital for the insane. In the found poem “Cracked Piano,” Peter Rawson Taft, who was William Howard Taft’s half-brother, writes home to his father, Alphonso Taft, who was attorney general in the Grant administration and secretary of war. Peter describes the other patients who laugh, remain silent, or grunt, and who all sit at a table where “The conversation is neither amusing/ nor instructive” (4). He also describes the conditions of the Cincinnati hospital, a place where,

Each patient has a separate

room with a carpet,

a bed, a table, a wash-stand,

a box, and one chair,

but no gas and no candles. (3)

Peter’s letter is preoccupied with the place in which he resides that he calls plain and hard, how lonely he is, and how he longs for visitors. In the other found poem, “No Occurrence of an Exciting Nature” from Peter’s letter, he writes of card games with other patients and of the lack of letters he’s received from friends or family, suggesting that he’s been forgotten during the time he’s been stowed away. What makes his letters provocative is the way Stever attends to the missed opportunity and wasted life of her ancestor, mostly forgotten by the historical record, but one The Lunatic Ball stands to correct. Her great-grandfather’s insanity may have been instigated by taking the prescribed medicine of the day. Peter studied classics at Yale, but a few months before graduation, he came down with Typhoid fever. He was given Calomel, a mercury containing drug. He survived the fever, but suffered from reoccurring headaches thereafter and was hospitalized, a placement that silenced family discourse about the unfortunate relative’s condition and eclipsed from the William Howard Taft Papers. It was only during Stever’s research for the book William Howard Taft and the 1905 U.S. Diplomatic Mission to Asia (Zhejiang University Press, 2012; English-language edition, 2015) that she uncovered the letters and her curiosity to explore such treatment of mental illness became the subject of her chapbook The Lunatic Ball.

The chapbook also contains poems that ruminate on representative treatment of the insane. The title poem explores the phenomena of lunatic balls, which were balls for those in such hospitals that allowed for “non-insane” people to watch, much like one might watch the proceedings of a trial or a congressional debate, but with music, food, dancing, and beverages being consumed. The poem opens with the evocative image of madmen cavorting,

Furious dancing gives way to screams;

five men stare, ghoulish, at the wall.

This is the lunatic ball. (6)

This exphrasis poem that responds to George Bellows’ painting “Dance in a Madhouse” presents both maddening displays of behavior while it simultaneously humanizes the individuals, pointing to the likely causes of mental illness like Calomel, women who were locked up when they sought separation from their husbands before divorce was a woman’s right, and fevers that brought on brain trauma. Stever also does something more. She gives us not just causation, but also intellectualizes the mad. She gives them smarts, self-awareness, and acuity about their situation, suggesting that such balls and hospitalizations did more to make women and men mad than any other explanatory experiences. She writes,

Behind a glass wall, well-dressed spectators, riveted,

sit amused. Looking at them looking, the patients

know they are through. (6)

Lunatic balls were considered humanitarian treatment even as they worked to reinscribe the separation between the mad and non-mad—the actors and voyeurs, dancers and watchers, sane and insane. Rather than viewing madness as a state of degradations along a vast line, the act of inviting some members of the society to see others as insane likely did more to make madness real than any dose of mercury.

Other poems in The Lunatic Ball meditate on variations of madness—the desire to be thin contrasted with the desire to eat comfort foods (“Animal Crackers”), women who dress as men to enable them to make art (“Horse Fair”), artists like Van Gogh who felt his phantom ear after it had been sliced off (“Van Gogh to His Mistress”), pickpockets, passerby of nunneries, animals who murder, the weirdness of the body. These are rich, evocative poems, poems that reflect on what madness meant in the late 1800s and what madness means today, nearly one hundred and fifty years later. In finely crafted poems, musical, lyric, and precise, Stever suggests inThe Lunatic Ball that we’re all spectators and dancers and the difficulty is knowing which side of viewing wall we’re on.

Laura Madeline Wiseman is the author of twenty books and chapbooks and the editor of Women Write Resistance: Poets Resist Gender Violence (Hyacinth Girl Press). Her recent books are Drink (BlazeVOX Books), Wake (Aldrich Press), Some Fatal Effects of Curiosity and Disobedience (Lavender Ink), The Bottle Opener (Red Dashboard), and the collaborative book The Hunger of the Cheeky Sisters (Les Femmes Folles) with artist Lauren Rinaldi. Her work has appeared in Prairie Schooner, Margie, Mid-American Review,Ploughshares, and Calyx.