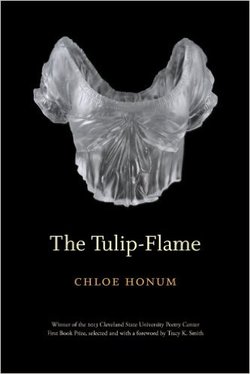

Paperback: 72 Pages

Publisher: Cleveland State University Poetry Center (2014)

Purchase: @ Amazon.com

Review by Jackson Holbert

I first stumbled upon Chloe Honum's work while flipping through a back issue of Poetry magazine. The poem I read first, “Spring,” happens to open Honum's first book, The Tulip Flame. “Spring,” a poem about a mother's suicide and the formlessness of sorrow—echoing Dickinson if not in language then in sentiment—serves as a good introduction to Honum's astounding use of language and image. The poem begins with the lines “Mother tried to take her life. / The icicles thawed”, and then describes how the speaker and the speaker's sister cope with the loss of their mother. The poem, in an incredible jump that relies on the very subtle instilling of the poem with images of lightness such as “birds flow from the woods' / fingertips” and “chained daises, prayed,” manages to find the lines:

All that falls is caught. Unless

it doesn't stop, like moonlight,

which has no pace to speak of,

falling through the cedar limbs,

falling through the rock.

With these lines gravity is infused back into the world of poem. The avoidance of grief present in both the language of the poem and the images can hold no longer. Or, perhaps even the poet finds deeper grief in the avoidance of language, of the moonlight that permeates everything.

One of Honum's most awe-inspiring skills is her ability to maintain a congruence with similes and metaphors throughout a poem and, at the same time, make meaning by quietly disrupting or modifying the congruity she has already established. Take the poem “Thirteen”:

The trees wrote their last scarlet notes.

Silence grew inside me. By winter

my voice felt like a bowl

of very still water;

for hours at a time nothing moved in it.

Here is the house: a table

beneath a golden light,

Mother's closed bedroom door,

a window. Here is the garden.

She wanted to move away

from us, I know,

and I'd hate to let her. Go,

I whispered, but alone,

while watching a sparrow

splash in a basin:

emerald water, spindly leaves, feathers.

The image of a “bowl of very still water” is established and inextricably connected with the poet's voice in the first stanza. In the last stanza, when the poet's voice is given a small sound, the water begins to move. This works, mostly, because one's expectations are overturned by the continuity of the metaphor that was originally established in a simile. One might not be surprised, or be surprised less, if Honum had simply presented the image of a bowl in the first stanza, rather than presenting the still water within a simile—inherently outside of the world—and followed it up with and related it to something inextricably part of the world of the poem but also signifying the abstract inside the imagined world of the poem.

Honum, a ballet dancer for most of her life, is always conscious of the poem as an extension of the body and the poem as a body unto itself. In an interview with the Poetry Society of America Honum states, “I remember my teacher yelling 'sloppy hands!' as I danced. What she meant was that I had forgotten my fingertips, that I wasn't dancing with every millimeter of my body.” This awareness of the whole body manifests itself, in part, in Honum's awareness of what we touch and what we see. Many of the poems are set—or seem to be set—in West Texas. They echo the calming, but at times, ominous openness such a landscape engenders in other work from or about the area such as Cormac McCarthy's Border Trilogy and The Mountain Goats' All Hail West Texas. Honum's landscapes—and one is attempted to chalk this up to Louise Gluck's influence on Honum—are nearly always extensions of the self rather than a thing outside of the self, as in the opening lines of “Spring II”: “Sister, it is a beautiful afternoon / and I am stuck in an evening / of soundless lightning.”

While there are a few slight weak spots in the book—one might be tempted to say the weakest poems are the villanelles—Honum, overall, provides us with a scintillating and regenerative look at grief and loss and love.

Publisher: Cleveland State University Poetry Center (2014)

Purchase: @ Amazon.com

Review by Jackson Holbert

I first stumbled upon Chloe Honum's work while flipping through a back issue of Poetry magazine. The poem I read first, “Spring,” happens to open Honum's first book, The Tulip Flame. “Spring,” a poem about a mother's suicide and the formlessness of sorrow—echoing Dickinson if not in language then in sentiment—serves as a good introduction to Honum's astounding use of language and image. The poem begins with the lines “Mother tried to take her life. / The icicles thawed”, and then describes how the speaker and the speaker's sister cope with the loss of their mother. The poem, in an incredible jump that relies on the very subtle instilling of the poem with images of lightness such as “birds flow from the woods' / fingertips” and “chained daises, prayed,” manages to find the lines:

All that falls is caught. Unless

it doesn't stop, like moonlight,

which has no pace to speak of,

falling through the cedar limbs,

falling through the rock.

With these lines gravity is infused back into the world of poem. The avoidance of grief present in both the language of the poem and the images can hold no longer. Or, perhaps even the poet finds deeper grief in the avoidance of language, of the moonlight that permeates everything.

One of Honum's most awe-inspiring skills is her ability to maintain a congruence with similes and metaphors throughout a poem and, at the same time, make meaning by quietly disrupting or modifying the congruity she has already established. Take the poem “Thirteen”:

The trees wrote their last scarlet notes.

Silence grew inside me. By winter

my voice felt like a bowl

of very still water;

for hours at a time nothing moved in it.

Here is the house: a table

beneath a golden light,

Mother's closed bedroom door,

a window. Here is the garden.

She wanted to move away

from us, I know,

and I'd hate to let her. Go,

I whispered, but alone,

while watching a sparrow

splash in a basin:

emerald water, spindly leaves, feathers.

The image of a “bowl of very still water” is established and inextricably connected with the poet's voice in the first stanza. In the last stanza, when the poet's voice is given a small sound, the water begins to move. This works, mostly, because one's expectations are overturned by the continuity of the metaphor that was originally established in a simile. One might not be surprised, or be surprised less, if Honum had simply presented the image of a bowl in the first stanza, rather than presenting the still water within a simile—inherently outside of the world—and followed it up with and related it to something inextricably part of the world of the poem but also signifying the abstract inside the imagined world of the poem.

Honum, a ballet dancer for most of her life, is always conscious of the poem as an extension of the body and the poem as a body unto itself. In an interview with the Poetry Society of America Honum states, “I remember my teacher yelling 'sloppy hands!' as I danced. What she meant was that I had forgotten my fingertips, that I wasn't dancing with every millimeter of my body.” This awareness of the whole body manifests itself, in part, in Honum's awareness of what we touch and what we see. Many of the poems are set—or seem to be set—in West Texas. They echo the calming, but at times, ominous openness such a landscape engenders in other work from or about the area such as Cormac McCarthy's Border Trilogy and The Mountain Goats' All Hail West Texas. Honum's landscapes—and one is attempted to chalk this up to Louise Gluck's influence on Honum—are nearly always extensions of the self rather than a thing outside of the self, as in the opening lines of “Spring II”: “Sister, it is a beautiful afternoon / and I am stuck in an evening / of soundless lightning.”

While there are a few slight weak spots in the book—one might be tempted to say the weakest poems are the villanelles—Honum, overall, provides us with a scintillating and regenerative look at grief and loss and love.

Jackson Holbert's work has appeared or is forthcoming in Radar Poetry, BOAAT, Minnesota Review, Tupelo Quarterly, and Thrush Poetry Journal, among others.