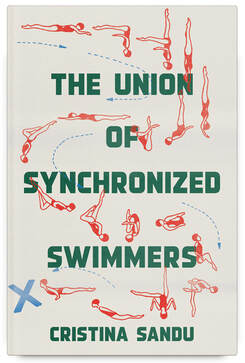

The Union of Synchronized Swimmers by Cristina Sandu

Review by Alina Stefanescu.

I.

In 1878, Ivan Turgenev published "Threshold," a short lyric dialogue between a god-like voice and a young girl choosing to stand apart from her family in the world. Leaving the village, choosing to reject inherited wisdom and origins, is a dangerous threshold, Turgenev suggests, there will be no family or community support. In this gamble, the question is whether the gain - the knowledge of beyond - is worth the loss of belonging, the end of specificity of a point on a map, the blurring of origins that defines the future and sets limit on expectation.

This threshold of choice for women is crossed repeatedly in Cristina Sandu's writing. Sandu, who identifies as Finnish-Romanian, was born in Helsinki in 1989, the year when the Berlin wall crumbled. The Union of Synchronized Swimmers, her second novel, won the 2020 Toisinkoinen Literary Prize for its original publication in Finnish. The English translation of this novel, recently published by Book*Hug Press, was translated entirely by the author. It is Sandu, herself, who brings her work over the border of language. And it is Sandu whose narratives complicate globalizations that make these motions possible.

The novel follows six ordinary girls who live in an Eastern European village that seems abandoned by the world. In the epigraph, the crane, porpoise, flamingo, and dolphin are linked as beings that live in relation to water, but these names also describe positions in synchronized swimming, a sport that Sandu locates "on the threshold between floating and sinking." One gets the sense that there are few choices: the characters invest in the logic of markets, for lack of a functioning alternative. They hope for a good outcome in the lottery of consumer preference.

Sandu highlights language's murky borders, and how this reflects on the alienated migrant labor behind globalization. Words which indicate belonging to a group are altered by the position one assumes in the water, and Sandu represents these divisions structurally by beginning with italicized ur-text, a story of origins, that gives us the development of the girls as a group. This ur-text is divided and continued in the novel, between chapters that name each of the six girls and where they have ended up.

"The girls started to play, though they were too old; their movements were aimless at first..." The land where they live doesn't "belong to any country," though its name means "Near Side of the River." This place, the point of origin, is overseen by the shadows of the metal and cigarette factories where the mothers work while the fathers seek temporary jobs abroad. There is a hilltop with a "blue-roofed monastery, and the remains of stone Lenins, the remnants of war memorials that survived the end of communism. Dogs and pigeons roam the streets.”

The six girls are not named in the italicized story: they are simply "the girls" meet at the river. A tv documentary introduces the girls to synchronized swimming, a "new sport involving women" who float separately, each mimicking the other in their movements. The girls begin to explore synchronized movement in the river - it becomes summer, the black swimsuits and meetings, the repetition of movements glimpsed on a screen, and the image of the swimsuits draped from tree branches "like crows - like fateful omens, people would say, but only afterwards."

To exist is to belong, to be named, to be recognized. The Far Side of the River is the neighboring town, and the Near Side was once close to the Far Side but the Near Side "refuses to belong to anyone to this day, and hence does not really exist." The Near Side is run by the Captain who owns the cigarette plant. Neoliberalism anoints the Captain a local king, for economic reasons. It's the Captain's largesse and self-promotion that creates local sports arenas. The power of men in this novel is economic: they determine freedom of movement, material well-being, and opportunity for the girls. For example, a nameless fiance who lives on the rich side of the river comes to visit; he brings the gift of a "first-rate deodorant," the currency of affection in under-privileged nations. The fiancee mocks her wet hair, but the girl doesn't care; belonging to the group of girls inoculates her against the local, or gives her a dream outside the hope of marrying a richer fellow from across the river.

Sandu's narrative tone is unsentimental, displaced, shorn of attachment. By withholding mention of the girls' families, Sandu makes it seem as if they do not exist. The girls are set apart by their swimming union. They roam the streets in tracksuits, and they belong to each other: they belong to motions they perfect in the river. The Captain notices the synchronized swimmers. He invites them to his Sports Complex, where they can be on his team.

"Since nothing is as beneficial for both financial profit and national pride as sports, the Near Side of the River has a sports complex the likes of which the neighboring countries can only dream," Sandu writes.

As the Tokyo Olympics scroll across my screen, I can't help noticing how astronomically lucrative sports has become--and how much extraordinary wealth in the United States is linked to it. Sports creates an arena of symbolic national competition where wealthy men can pit their purchased sports team against another sports team, thus winning symbolic points for their gladiatorial dreams.

Who are these girls in the newspaper photo titled: "TEAM OF SYNCHRONIZED SWIMMERS FORMED BY GIRLS FROM CIGARETTE FACTORY"? They are wearing so much make-up in the photo that they look identical, but looking closely one can see each girl is "terrified in her own way". The news photo frames the book, creating a context for the capitalist realist lie of self-actualization. The girls don't come from a town or a place: they belong to the Cigarette Factory and the Captain. They belong to neoliberalism's highest bidder.

When The Far Side of the River notices the girls, they have become ideal, a marketable commodity. Suddenly, they are visible, and given visas to join the sports club on the Far Side. "Sports is important on both sides of the river: a fragile link between two countries looking away from each other," and sport also erases them, as we are told of international competitions where "the athletes of one side carry the flag of the other and even sing their national anthem." Their black swimsuits turn yellow on the other side of the border; their bodies market by the commodification.

In the evenings, when they fell on their beds like lumbered trees, the girls felt the movement of water inside their bodies. It rocked them to a place that belonged neither to this nor to that side of the river. The beauty of the threshold: on the other side of it, everything was still possible. Perhaps they were happier then, more complete and satisfied, then they ever had been or would be.

Sandu credits Peter Handke's Slow Homecoming with this idea of "the beauty of the threshold," and I couldn't help reading a deep sadness and displacement in it, the longing of migrant labor, the loss of community and language - and Turgenev's threshold. Modern individualism posits ambition, hard work, and bootstraps as a recipe for self-fulfillment through personal dreams. But dreams aren't operative in Sandu's lands: what matters is opportunity. The characters aren't driven by chances to become what they have seen on television. Men and romance serve as transactional frames for the next economic possibility. For the girls, there is no personal intimacy that provides lasting meaning outside the financial consideration. And there is no "dream" that is not a commodity presented by media.

II.

The lotteries of neoliberalism run like a seam through the girls' stories, setting the tone for the unpredictable, mundane efforts at survival. We get to know the girls as individuals in the chapters that describe where the girls go after leaving the village. It is in these lonely, alienated coordinates that we finally meet the self-actualizing versions of Anita, Paulina, Sandra, Betty, Nina, Lidia.

Anita is studying in Helsinki. She describes her life in the room without Finnish decor, without paraphernalia from her "own country" which remains nameless. (This country itself is a secret throughout the book, as if danger comes from association.) Anita's affair with a superhero named Blue Flame also reveals how much is unspoken between migrants - they converse in English, even though Blue Flame lets his native tongue slip, and Anita recognizes this tongue as her own, though neither claims it or relates at the origin. Blue Flame tells her about "the migrating olive trees," a silvery species summoned into the US by the longing of "homesick Eastern European settlers" who carried the seeds over oceans.

Paulina is in San Luis Obispo, a port town where she starts a business taking care of the elderly, getting paid $3,000 a month to do what would never happen in her own country where "old people die at home". To support herself abroad, Paulina becomes part of the care economy which is often staffed by migrants.

Sandra is hitchhiking through the Pyrenees to get to Paris when she hops into a car with a fairly creepy Frenchman, and it's interesting how the concern with creepiness, the me-too-moment of that power dynamic, tastes like a bourgeois melodrama in the context of lack of agency, of needing to get from one place to another. As the man moves in a direction which may be Paris, he describes the scar that divides his face, the result of a childhood accident when he got too close to a blind lion. In the back seat, under magazines, there is a scythe, a constant sense of danger. We are left not knowing what happens to Sandra.

Betty sits at a casino table in San Martin playing Texas Hold 'Em with the last of her money. When a man in Bucharest says there is "work for everyone" in San Martin - "You leave poor but you come back... wealthier"- she and her boyfriend, Lux, use money from his black-market cell phone business to plan her voyage to San Martin. She hitches a ride with a trucker to Paris, and flies to San Martin, only to discover the only available work is pimped prostitution. Eventually, Betty finds herself in the casino, trying to make enough money to go back. And she makes enough money to get to Paris, where word-of-mouth says that flights to Bucharest are cheap. In the airport, Betty discovers that word-of-mouth was wrong, and she can't get to Bucharest. When a stranger offers to pay her fare if she will fly "candy" back to Romania for him, Betty agrees. In this casual, transactional exchange, she becomes a drug mule. Betty uses the language of gambling to describe the scenario: "I will return, after all, a winner." The reader is left without knowing whether Betty arrives, gets busted, or survives. One is left with the feeling that the unnamed male pimps are the winners.

Nina is in Rome, at a cafe. She reads an Italian book and discovers her own thoughts in a language that's not her own: "sentences move through her." She speaks to the waiter, who is surprised that she isn't Italian, and Nina laughs when he asks where she learned to speak Italian. "Nothing stays inside one language" for Nina; "each thought begets its double." As Nina studies this new language, she notices that:

The endings of words, which are forever changing in her mother tongue, straighten. Diminutives, usually everywhere, fade.

New words or verbs appear (she mentions "to be," as one of those absent from her mother tongue). Nina contrasts the Russian word, solnyshka, which means "little sun", with the average sun that doesn't absorb its diminutives in Italian. The solnyshka implies a child's sun, a little sun, an innocent sun, which whispers while inking behind the river. Sandu includes both the Cyrillic and the transliterated form of this word. This particular intimacy is also true of Romanian, which follows Russian in giving us "little suns." I miss those little suns and little soups so much in English, where the world is starker, more demanding, more accumulative rather than internally-modified at the level of the word.

The novel ends with Lidia, who returns to the Near Side of the River, to the grotesque curiosity of the village women, their jokes rimmed in fatalism, to the plum wine filling ceramic mugs, to the same ruins and ways of speaking. The Bird Feeder who used to raise and train doves for competitions that no longer exist describes the new temporality. He hopes to make money from solar panels and energy, the latest lottery afforded by businessmen who are coming to survey his property from the Far Side of the River -- "all new things come from there," he says. No one swims in the river anymore. Poison has been found in the groundwater, the river, the gardens, the fish and birds. A new pesticide billed as "an improvement" caused the fish kills and featherless birds. Although it’s been years since the pesticide was used, "things don't disappear just like that," the Bird Feeder tells Lidia.

III.

At the village tavern, the men drink and spit sunflower shells on the floor, their eyes on the television, waiting to see "their girls" compete. They are joined in excitement over this team that "belongs to them, like berries and fruits growing on their soil". The claimed origin is more real than the fact of another country's economic claim to the team.

When the girls don't appear on the screen, the tavern keeper is furious, he realizes they fled. The men console themselves with the hope of reporters coming to see the land that made the girls - but I wonder if these reporters can (or will) present a humane picture of a place that doesn't exist. The girls are in different places all over the world, disoriented, lacking a sense of direction. The town looks the same, except for "the mute swimming pool". The river is the character, it continues to ramble through the land, indifference to borders. No one comes to the river anymore. The river of ruins gape open, and what is there to say? Who belongs to this unspoken place?

It is television that inspires the girls to start swimming, to fashion themselves differently from the village, and it is this fashioning that becomes marketable, that is a commodity which enables them to escape. I watch the nearest screen, a slight nausea rising as medals claim bodies, countries, borders, and nations.

I.

In 1878, Ivan Turgenev published "Threshold," a short lyric dialogue between a god-like voice and a young girl choosing to stand apart from her family in the world. Leaving the village, choosing to reject inherited wisdom and origins, is a dangerous threshold, Turgenev suggests, there will be no family or community support. In this gamble, the question is whether the gain - the knowledge of beyond - is worth the loss of belonging, the end of specificity of a point on a map, the blurring of origins that defines the future and sets limit on expectation.

This threshold of choice for women is crossed repeatedly in Cristina Sandu's writing. Sandu, who identifies as Finnish-Romanian, was born in Helsinki in 1989, the year when the Berlin wall crumbled. The Union of Synchronized Swimmers, her second novel, won the 2020 Toisinkoinen Literary Prize for its original publication in Finnish. The English translation of this novel, recently published by Book*Hug Press, was translated entirely by the author. It is Sandu, herself, who brings her work over the border of language. And it is Sandu whose narratives complicate globalizations that make these motions possible.

The novel follows six ordinary girls who live in an Eastern European village that seems abandoned by the world. In the epigraph, the crane, porpoise, flamingo, and dolphin are linked as beings that live in relation to water, but these names also describe positions in synchronized swimming, a sport that Sandu locates "on the threshold between floating and sinking." One gets the sense that there are few choices: the characters invest in the logic of markets, for lack of a functioning alternative. They hope for a good outcome in the lottery of consumer preference.

Sandu highlights language's murky borders, and how this reflects on the alienated migrant labor behind globalization. Words which indicate belonging to a group are altered by the position one assumes in the water, and Sandu represents these divisions structurally by beginning with italicized ur-text, a story of origins, that gives us the development of the girls as a group. This ur-text is divided and continued in the novel, between chapters that name each of the six girls and where they have ended up.

"The girls started to play, though they were too old; their movements were aimless at first..." The land where they live doesn't "belong to any country," though its name means "Near Side of the River." This place, the point of origin, is overseen by the shadows of the metal and cigarette factories where the mothers work while the fathers seek temporary jobs abroad. There is a hilltop with a "blue-roofed monastery, and the remains of stone Lenins, the remnants of war memorials that survived the end of communism. Dogs and pigeons roam the streets.”

The six girls are not named in the italicized story: they are simply "the girls" meet at the river. A tv documentary introduces the girls to synchronized swimming, a "new sport involving women" who float separately, each mimicking the other in their movements. The girls begin to explore synchronized movement in the river - it becomes summer, the black swimsuits and meetings, the repetition of movements glimpsed on a screen, and the image of the swimsuits draped from tree branches "like crows - like fateful omens, people would say, but only afterwards."

To exist is to belong, to be named, to be recognized. The Far Side of the River is the neighboring town, and the Near Side was once close to the Far Side but the Near Side "refuses to belong to anyone to this day, and hence does not really exist." The Near Side is run by the Captain who owns the cigarette plant. Neoliberalism anoints the Captain a local king, for economic reasons. It's the Captain's largesse and self-promotion that creates local sports arenas. The power of men in this novel is economic: they determine freedom of movement, material well-being, and opportunity for the girls. For example, a nameless fiance who lives on the rich side of the river comes to visit; he brings the gift of a "first-rate deodorant," the currency of affection in under-privileged nations. The fiancee mocks her wet hair, but the girl doesn't care; belonging to the group of girls inoculates her against the local, or gives her a dream outside the hope of marrying a richer fellow from across the river.

Sandu's narrative tone is unsentimental, displaced, shorn of attachment. By withholding mention of the girls' families, Sandu makes it seem as if they do not exist. The girls are set apart by their swimming union. They roam the streets in tracksuits, and they belong to each other: they belong to motions they perfect in the river. The Captain notices the synchronized swimmers. He invites them to his Sports Complex, where they can be on his team.

"Since nothing is as beneficial for both financial profit and national pride as sports, the Near Side of the River has a sports complex the likes of which the neighboring countries can only dream," Sandu writes.

As the Tokyo Olympics scroll across my screen, I can't help noticing how astronomically lucrative sports has become--and how much extraordinary wealth in the United States is linked to it. Sports creates an arena of symbolic national competition where wealthy men can pit their purchased sports team against another sports team, thus winning symbolic points for their gladiatorial dreams.

Who are these girls in the newspaper photo titled: "TEAM OF SYNCHRONIZED SWIMMERS FORMED BY GIRLS FROM CIGARETTE FACTORY"? They are wearing so much make-up in the photo that they look identical, but looking closely one can see each girl is "terrified in her own way". The news photo frames the book, creating a context for the capitalist realist lie of self-actualization. The girls don't come from a town or a place: they belong to the Cigarette Factory and the Captain. They belong to neoliberalism's highest bidder.

When The Far Side of the River notices the girls, they have become ideal, a marketable commodity. Suddenly, they are visible, and given visas to join the sports club on the Far Side. "Sports is important on both sides of the river: a fragile link between two countries looking away from each other," and sport also erases them, as we are told of international competitions where "the athletes of one side carry the flag of the other and even sing their national anthem." Their black swimsuits turn yellow on the other side of the border; their bodies market by the commodification.

In the evenings, when they fell on their beds like lumbered trees, the girls felt the movement of water inside their bodies. It rocked them to a place that belonged neither to this nor to that side of the river. The beauty of the threshold: on the other side of it, everything was still possible. Perhaps they were happier then, more complete and satisfied, then they ever had been or would be.

Sandu credits Peter Handke's Slow Homecoming with this idea of "the beauty of the threshold," and I couldn't help reading a deep sadness and displacement in it, the longing of migrant labor, the loss of community and language - and Turgenev's threshold. Modern individualism posits ambition, hard work, and bootstraps as a recipe for self-fulfillment through personal dreams. But dreams aren't operative in Sandu's lands: what matters is opportunity. The characters aren't driven by chances to become what they have seen on television. Men and romance serve as transactional frames for the next economic possibility. For the girls, there is no personal intimacy that provides lasting meaning outside the financial consideration. And there is no "dream" that is not a commodity presented by media.

II.

The lotteries of neoliberalism run like a seam through the girls' stories, setting the tone for the unpredictable, mundane efforts at survival. We get to know the girls as individuals in the chapters that describe where the girls go after leaving the village. It is in these lonely, alienated coordinates that we finally meet the self-actualizing versions of Anita, Paulina, Sandra, Betty, Nina, Lidia.

Anita is studying in Helsinki. She describes her life in the room without Finnish decor, without paraphernalia from her "own country" which remains nameless. (This country itself is a secret throughout the book, as if danger comes from association.) Anita's affair with a superhero named Blue Flame also reveals how much is unspoken between migrants - they converse in English, even though Blue Flame lets his native tongue slip, and Anita recognizes this tongue as her own, though neither claims it or relates at the origin. Blue Flame tells her about "the migrating olive trees," a silvery species summoned into the US by the longing of "homesick Eastern European settlers" who carried the seeds over oceans.

Paulina is in San Luis Obispo, a port town where she starts a business taking care of the elderly, getting paid $3,000 a month to do what would never happen in her own country where "old people die at home". To support herself abroad, Paulina becomes part of the care economy which is often staffed by migrants.

Sandra is hitchhiking through the Pyrenees to get to Paris when she hops into a car with a fairly creepy Frenchman, and it's interesting how the concern with creepiness, the me-too-moment of that power dynamic, tastes like a bourgeois melodrama in the context of lack of agency, of needing to get from one place to another. As the man moves in a direction which may be Paris, he describes the scar that divides his face, the result of a childhood accident when he got too close to a blind lion. In the back seat, under magazines, there is a scythe, a constant sense of danger. We are left not knowing what happens to Sandra.

Betty sits at a casino table in San Martin playing Texas Hold 'Em with the last of her money. When a man in Bucharest says there is "work for everyone" in San Martin - "You leave poor but you come back... wealthier"- she and her boyfriend, Lux, use money from his black-market cell phone business to plan her voyage to San Martin. She hitches a ride with a trucker to Paris, and flies to San Martin, only to discover the only available work is pimped prostitution. Eventually, Betty finds herself in the casino, trying to make enough money to go back. And she makes enough money to get to Paris, where word-of-mouth says that flights to Bucharest are cheap. In the airport, Betty discovers that word-of-mouth was wrong, and she can't get to Bucharest. When a stranger offers to pay her fare if she will fly "candy" back to Romania for him, Betty agrees. In this casual, transactional exchange, she becomes a drug mule. Betty uses the language of gambling to describe the scenario: "I will return, after all, a winner." The reader is left without knowing whether Betty arrives, gets busted, or survives. One is left with the feeling that the unnamed male pimps are the winners.

Nina is in Rome, at a cafe. She reads an Italian book and discovers her own thoughts in a language that's not her own: "sentences move through her." She speaks to the waiter, who is surprised that she isn't Italian, and Nina laughs when he asks where she learned to speak Italian. "Nothing stays inside one language" for Nina; "each thought begets its double." As Nina studies this new language, she notices that:

The endings of words, which are forever changing in her mother tongue, straighten. Diminutives, usually everywhere, fade.

New words or verbs appear (she mentions "to be," as one of those absent from her mother tongue). Nina contrasts the Russian word, solnyshka, which means "little sun", with the average sun that doesn't absorb its diminutives in Italian. The solnyshka implies a child's sun, a little sun, an innocent sun, which whispers while inking behind the river. Sandu includes both the Cyrillic and the transliterated form of this word. This particular intimacy is also true of Romanian, which follows Russian in giving us "little suns." I miss those little suns and little soups so much in English, where the world is starker, more demanding, more accumulative rather than internally-modified at the level of the word.

The novel ends with Lidia, who returns to the Near Side of the River, to the grotesque curiosity of the village women, their jokes rimmed in fatalism, to the plum wine filling ceramic mugs, to the same ruins and ways of speaking. The Bird Feeder who used to raise and train doves for competitions that no longer exist describes the new temporality. He hopes to make money from solar panels and energy, the latest lottery afforded by businessmen who are coming to survey his property from the Far Side of the River -- "all new things come from there," he says. No one swims in the river anymore. Poison has been found in the groundwater, the river, the gardens, the fish and birds. A new pesticide billed as "an improvement" caused the fish kills and featherless birds. Although it’s been years since the pesticide was used, "things don't disappear just like that," the Bird Feeder tells Lidia.

III.

At the village tavern, the men drink and spit sunflower shells on the floor, their eyes on the television, waiting to see "their girls" compete. They are joined in excitement over this team that "belongs to them, like berries and fruits growing on their soil". The claimed origin is more real than the fact of another country's economic claim to the team.

When the girls don't appear on the screen, the tavern keeper is furious, he realizes they fled. The men console themselves with the hope of reporters coming to see the land that made the girls - but I wonder if these reporters can (or will) present a humane picture of a place that doesn't exist. The girls are in different places all over the world, disoriented, lacking a sense of direction. The town looks the same, except for "the mute swimming pool". The river is the character, it continues to ramble through the land, indifference to borders. No one comes to the river anymore. The river of ruins gape open, and what is there to say? Who belongs to this unspoken place?

It is television that inspires the girls to start swimming, to fashion themselves differently from the village, and it is this fashioning that becomes marketable, that is a commodity which enables them to escape. I watch the nearest screen, a slight nausea rising as medals claim bodies, countries, borders, and nations.

Cristina Sandu was born in 1989 in Helsinki to a Finnish-Romanian family who loved books. She studied literature at the University of Helsinki and the University of Edinburgh and speaks six languages. She currently lives in the UK and works as a full-time writer. Her debut novel, The Whale Called Goliath (2017), was nominated for the Finlandia Prize, the most prestigious literary prize in Finland. The Union of Synchronized Swimmers, which won the 2020 Toisinkoinen Literary Prize, is her first book to be published in English.