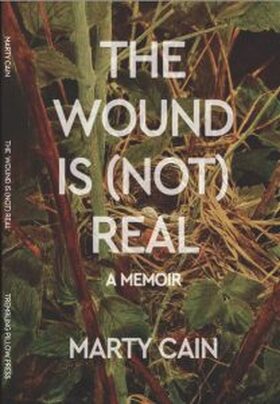

The Wound is (Not) Real: A Memoir by Marty Cain

The Wound is (Not) Real: A Memoir by Marty Cain

Publisher: Trembling Pillow Press, 2022

Purchase @ Trembling Pillow Press

Publisher: Trembling Pillow Press, 2022

Purchase @ Trembling Pillow Press

Review by J.B. Stone.

Although I’ve only met Marty Cain once, after reading his new Hybrid-Prose Poetry collection, The Wound is (Not) Real: A Memoir, I feel like I’ve met him on a thousand more occasions. Starting with the prologue; there is a volatile mixture of visceral imagery, anaphoric rhythm, and stark personal narrative that encompasses so many different feelings. Don’t be fooled in the titling: the wound here is real, and it lingers throughout the landscapes of this collection.

In the prologue which doubles as a dedication to Cain’s brother Alex, there is no hesitation, no pause, no moment to breathe; just a chaotic purge of imagery and narrative belted throughout this introductory piece. The experiences of seizures, the ultraviolent sensory of watching a loved one convulse, growing up in a household of routines revolved around the mass of empathy, routines built from the foundations of caring for a loved one. In one of the most striking passages, Cain speaks through his own brother’s hardship,

“I remember a time.

I remember my parents would call 911. It was my job to watch for the ambulance, running in my socks across waxed floors, and then squatting in the corner by the kitchen window. I remember the blue skin, the men wearing blue pants and blue jackets with bags that were blue, and carrying oxygen tanks, then sticking a syringe in my brother’s ass while I’d look away.

I remember thinking. He could die.

I remember not crying, thinking, Why is this normal.”

There are a lot of moments in literature, where disabled folks and their struggle is used to either be exploited as some burden to a family, or as the catalyst for some self-satisfied “savior” narrative. Neither of this is true here. Cain’s love for his brother is one of informed authenticity, a love that carefully understands this sort of language and makes it clear that the story here is not retold on behalf of his brother, but alongside him. Cain not only invites readers into his past, into the confines of his own childhood home, but invites the most meaningful characters in his life to be a forefront in his work, rather than a mere background. In those last lines, on the question of normality, readers may also see that difficult, yet necessary bridge between the personal and political coming to fruition. Why in the richest country in the world, Disabled lives still feel the brunt of a nation consumed by the campaigns against social programs.

This prologue also leads into the second prose piece, Goodbye Arcadia, a heartbreaking account on Cain’s experiences as the survivor of sexual assault. There is obviously a courage and strength that comes with this confessional. Yet Cain reminds readers why no one should have to be courageous and strong in the first place, especially in the face of traumas no one should have to bare. Goodbye Arcadia, like many of the accounts here, is written from a place of processing, and from a quarter life of bottled silence, Cain once again uncorks,

“O don’t tell me you don’t know the finger of god, don’t say you were asleep when we walked into the room, you float like a gator, you play like a possum. You smell like a wound. You fingered the red. I sank into your soul from the ceiling supports. I was scared of sleepovers”

In the next piece, Cain bleeds his past into the atlas of Upstate NY through Wordsworth Poem, using Wordsworth’s ecopoetic lore about walking to the edge of a river and seeing a pile of garments, and the next day, he learns that they belonged to a man that drowned. In a 21st century reboot, Cain knows the person who drowned in those garments,

“And form is a feeling.

And form is a garment.

And in my mind, I return to the clothes. I return to the discarded excess, to the pile that signifies death before we know its name; I return to seeing my brother emptied and seizing on the living room floor.”

Reflecting on Wordsworth’s work and comparing that return to his own, not only signifies the callback to the prologue, but signifies the return to tragedy, the return to watching it unfold, the return to scrambling and loathing in the aftermath of watching a loved one die over and over again. Death is perhaps the most infamous archetype in all of literature, whether that is poetry, fiction, or non-fiction, and death is surely no stranger to this collection.

Another poet, one who Cain regularly credits as a major influence in his own work, a person whose bled their own past into the countrysides they know all too well: Frank Stanford. Stanford not only made death a recurring theme in his work, but a recurring character. Death has a form here, and it’s prevalent in this Frank Stanford-inspired poem, Rural Thrash, Vol. 3., especially in the last two lines,

“THERE’S A BODY IN THE BACK OF THE FIELD YOU OWN

THERE’S AN UNWHITE BODY IN THE FIELD YOU OWN”

This interpretation can take so many forms, and I think in these lasting lines it’s part of what makes this free-verse poem so beautiful. Is the “unwhite” the body of someone who has faced so much shadow, their presence feels they’ve been buried in a tomb, unseen by anyone else’s light? Is it a commentary on the unmarked gravestones of working class Black folks, many of whom even here in NY State remain sort of entombed without a proper memorial (Central Park was built over the grounds of NY’s Black Wall Street, and no one speaks of that as much as they should)? Or is this person not buried at all, but just a spirit or a living soul wandering this field? Is this a moment of pastoral existentialism? The territorial pissings our oppressive system leaves on the land it claims to protect? It could be all of this, and it’s a welcomed vagueness, well-placed in a landscape shaped by the complete opposite.

Self Portrait with Go Fuck Yourself, another powerful piece, acts as the alternative final text in a work that pulls from so many places many might not want to venture. Cain tells and shows at the same time. Repeatedly throughout much of the collection, the wound is explained as a site of trauma, but Cain tells us, “When I write I crawl angrily out from myself.” However, in this poem, Cain also shows us the self he is crawling out from,

“I pull a ribbon from my innards and call it virtue

I call it a mother fox rooting through piles of leaves

I call it a dying planet I knew as a child”

Each detail depicts something more carnal, more disruptive, more lascivious. Cain doesn’t force-feed his trauma down everyone’s brain, yet he doesn’t wrap it in a sugared coat of subtleties and false affectations either. The wound is one of many trench-deep cuts encircled in the cutthroat autopsy of memories, memories of toxic patriarchy, toxic masculinity, depression, PTSD, SA, and ableism. Although Cain’s writing shows an undeterred love for family, for childhood friends, for the people in one’s life that keep them moving, Cain isn’t writing for the flowers coming to bloom, he is writing for the withering buds that long to be pollinated. Not all writing is supposed to leave its reader with a sense of hope. Cain realizes that his truths are not ready to provide that either. This isn’t to say that the final text, Holy Valence, isn’t a work that ends things on a lighter note. Rather, it’s a context of unrelenting ethos and bitter pills, continuing to stay with readers even after they’ve turned the last page.

Although I’ve only met Marty Cain once, after reading his new Hybrid-Prose Poetry collection, The Wound is (Not) Real: A Memoir, I feel like I’ve met him on a thousand more occasions. Starting with the prologue; there is a volatile mixture of visceral imagery, anaphoric rhythm, and stark personal narrative that encompasses so many different feelings. Don’t be fooled in the titling: the wound here is real, and it lingers throughout the landscapes of this collection.

In the prologue which doubles as a dedication to Cain’s brother Alex, there is no hesitation, no pause, no moment to breathe; just a chaotic purge of imagery and narrative belted throughout this introductory piece. The experiences of seizures, the ultraviolent sensory of watching a loved one convulse, growing up in a household of routines revolved around the mass of empathy, routines built from the foundations of caring for a loved one. In one of the most striking passages, Cain speaks through his own brother’s hardship,

“I remember a time.

I remember my parents would call 911. It was my job to watch for the ambulance, running in my socks across waxed floors, and then squatting in the corner by the kitchen window. I remember the blue skin, the men wearing blue pants and blue jackets with bags that were blue, and carrying oxygen tanks, then sticking a syringe in my brother’s ass while I’d look away.

I remember thinking. He could die.

I remember not crying, thinking, Why is this normal.”

There are a lot of moments in literature, where disabled folks and their struggle is used to either be exploited as some burden to a family, or as the catalyst for some self-satisfied “savior” narrative. Neither of this is true here. Cain’s love for his brother is one of informed authenticity, a love that carefully understands this sort of language and makes it clear that the story here is not retold on behalf of his brother, but alongside him. Cain not only invites readers into his past, into the confines of his own childhood home, but invites the most meaningful characters in his life to be a forefront in his work, rather than a mere background. In those last lines, on the question of normality, readers may also see that difficult, yet necessary bridge between the personal and political coming to fruition. Why in the richest country in the world, Disabled lives still feel the brunt of a nation consumed by the campaigns against social programs.

This prologue also leads into the second prose piece, Goodbye Arcadia, a heartbreaking account on Cain’s experiences as the survivor of sexual assault. There is obviously a courage and strength that comes with this confessional. Yet Cain reminds readers why no one should have to be courageous and strong in the first place, especially in the face of traumas no one should have to bare. Goodbye Arcadia, like many of the accounts here, is written from a place of processing, and from a quarter life of bottled silence, Cain once again uncorks,

“O don’t tell me you don’t know the finger of god, don’t say you were asleep when we walked into the room, you float like a gator, you play like a possum. You smell like a wound. You fingered the red. I sank into your soul from the ceiling supports. I was scared of sleepovers”

In the next piece, Cain bleeds his past into the atlas of Upstate NY through Wordsworth Poem, using Wordsworth’s ecopoetic lore about walking to the edge of a river and seeing a pile of garments, and the next day, he learns that they belonged to a man that drowned. In a 21st century reboot, Cain knows the person who drowned in those garments,

“And form is a feeling.

And form is a garment.

And in my mind, I return to the clothes. I return to the discarded excess, to the pile that signifies death before we know its name; I return to seeing my brother emptied and seizing on the living room floor.”

Reflecting on Wordsworth’s work and comparing that return to his own, not only signifies the callback to the prologue, but signifies the return to tragedy, the return to watching it unfold, the return to scrambling and loathing in the aftermath of watching a loved one die over and over again. Death is perhaps the most infamous archetype in all of literature, whether that is poetry, fiction, or non-fiction, and death is surely no stranger to this collection.

Another poet, one who Cain regularly credits as a major influence in his own work, a person whose bled their own past into the countrysides they know all too well: Frank Stanford. Stanford not only made death a recurring theme in his work, but a recurring character. Death has a form here, and it’s prevalent in this Frank Stanford-inspired poem, Rural Thrash, Vol. 3., especially in the last two lines,

“THERE’S A BODY IN THE BACK OF THE FIELD YOU OWN

THERE’S AN UNWHITE BODY IN THE FIELD YOU OWN”

This interpretation can take so many forms, and I think in these lasting lines it’s part of what makes this free-verse poem so beautiful. Is the “unwhite” the body of someone who has faced so much shadow, their presence feels they’ve been buried in a tomb, unseen by anyone else’s light? Is it a commentary on the unmarked gravestones of working class Black folks, many of whom even here in NY State remain sort of entombed without a proper memorial (Central Park was built over the grounds of NY’s Black Wall Street, and no one speaks of that as much as they should)? Or is this person not buried at all, but just a spirit or a living soul wandering this field? Is this a moment of pastoral existentialism? The territorial pissings our oppressive system leaves on the land it claims to protect? It could be all of this, and it’s a welcomed vagueness, well-placed in a landscape shaped by the complete opposite.

Self Portrait with Go Fuck Yourself, another powerful piece, acts as the alternative final text in a work that pulls from so many places many might not want to venture. Cain tells and shows at the same time. Repeatedly throughout much of the collection, the wound is explained as a site of trauma, but Cain tells us, “When I write I crawl angrily out from myself.” However, in this poem, Cain also shows us the self he is crawling out from,

“I pull a ribbon from my innards and call it virtue

I call it a mother fox rooting through piles of leaves

I call it a dying planet I knew as a child”

Each detail depicts something more carnal, more disruptive, more lascivious. Cain doesn’t force-feed his trauma down everyone’s brain, yet he doesn’t wrap it in a sugared coat of subtleties and false affectations either. The wound is one of many trench-deep cuts encircled in the cutthroat autopsy of memories, memories of toxic patriarchy, toxic masculinity, depression, PTSD, SA, and ableism. Although Cain’s writing shows an undeterred love for family, for childhood friends, for the people in one’s life that keep them moving, Cain isn’t writing for the flowers coming to bloom, he is writing for the withering buds that long to be pollinated. Not all writing is supposed to leave its reader with a sense of hope. Cain realizes that his truths are not ready to provide that either. This isn’t to say that the final text, Holy Valence, isn’t a work that ends things on a lighter note. Rather, it’s a context of unrelenting ethos and bitter pills, continuing to stay with readers even after they’ve turned the last page.

J.B. Stone (he/they) is a Neurodivergent/Autistic slam poet, writer, editor, and critic from Brooklyn, NY now residing in Buffalo, NY. They’re the EIC/reviews Editor at Variety Pack, and are a flash fiction reader for Split Lip Magazine. Nominated for the Best of the Net and Best Small Fictions, his work is forthcoming or has appeared in The Citron Review, Atticus Review, Peach Mag, Chicago Review of Books, among other spaces.