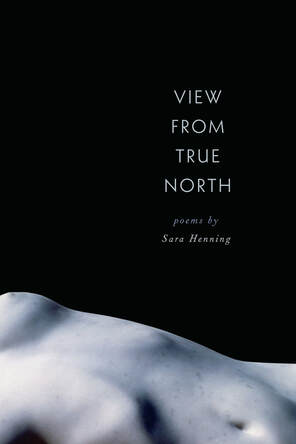

View from True North by Sara Henning

Paperback: 88 pages

Publisher: Southern Illinois University Press (Crab Orchard Series in Poetry), 2018

Purchase: @ SIU Press

Review by Jennifer Martelli.

The violence and tragedy in Sarah Henning’s masterful poetry collection View From True North is hereditary; it transforms bodies; it forces a new language. In her poem, “Song,” Henning defines and re-defines the sounds of this trauma:

Can you hear it? / the song acutest at its vanishing? / Her father’s heart?

~

Her body’s brute arpeggio? / Is it a song of erasure gone wrong? / Do you call it

~

Bone of my bones / Flesh of my flesh / A fist-shaped longing chiseled out of light?

We are confronted, poem after achingly beautiful poem, with a legacy born from poverty, alcoholism, sexual assault, and suicide; but Henning also pays homage to a legacy of poetry and its music. The collection, in which bodies are crushed into starlight, or transformed into birds, or burnt to ash, is anchored by the poet’s vision—her words and her poetic lineage. The sonnet sequences in the collection remind us of the strength of naming things, of containing emotion within the line and the form.

The poems revel in and rely on transformation. As in classical mythology, the gods’ way of saving or punishing is by metamorphosis. The birds, the stars, the ashes are what remain after the violence. The opening poem, “First Murmuration,” introduces us to a family’s brutality and to transformation as survival:

When I say a son

is broken open by his father

is becoming a starling,

I mean feathers are unfurling

from his skin . . . .

. . . .When I say a son broken

open, I mean

a son shape-shifting

past the velvet scrim

a son who learns

to leave his body

at the first slow pierce

of his father’s song.

The grandfather, a character who tortures and who is tortured by his own sexuality, is the progenitor—the Adam—of the lineage. In a section of Henning's sonnet sequence, “The End of the Unified Field,” the grandfather is dessicated:

“Hail, when I meant I’ve clutched my inheritance until

it has flown . . . .

I watch him ease back into atomic

ordering. Sutures of bone interlacing wind.

His body confabulating like stars . . . .

After his death (or even in death), he is still capable of sadism. In “Mandoline,” the mother “must/witness his cremation,” but “she’ll laugh/her way past the funeral home/director. . .trusting she’s finally mastered her father.” But are words and sounds capable of truly overcoming decades of pain, or are they “. . .another illusive/dialectic . . . ?” Trauma distorts words, renders them untrustworthy and slippery, at times, it stifles them. Henning writes,

I have no words for the guilt that falls with this body,

the animal, serpentine, that rises with his breath.

No words for why he’s trusted with girls--

sisters, nieces, the next ripe surge of daughters--

why my aunt won’t leave him alone with her son.

Henning reaches back to her poetic predecessors for her true north. Referencing masters such as Jorie Graham, Marie Howe, Lynda Hull, Yeats, Rilke, Mark Doty, she places her story in the tide of linguistic transformations; one that is ancient, yet looks to the future. Henning’s poem, “How to Pray,” is a conversation with Marie Howe:

Write the word

brother over and over until it means

love, until it means save yourself, until it means

beautiful enough to disappear.

If there is survival in this story, it is gotten through poetry; if there is a center in this disintegration, it is the starlings, which “bred mercilessly, roosting in hordes.” The pain as well as the ability to transform is inherited, earned through violence, which forces a different form of communication. In “Drunk Again, He Pushes Her,” Henning states

if the alibi she learns to mouth is quilled

into her blood like a siren song, I’ll say this

is how I’m falling this is how I fell—gravity

my heirloom, my bluntly conjured flare.

View From True North is vast in its scope, its horror, its beauty. I would read a poem, put the book down, and then think deeply about the entwined natures of grief, trauma, family, and language. Sarah Henning has placed us in a linguistic lineage that laments an old pain. It is from this place, though, that we are given a new language, a new way to continue:

When hope

no longer consoles us,

we unhinge, we crash

-land, we sing in our sleep.

How else, after all, will we

master our mating song?

Sara Henning is the author of two volumes of poetry, most recently View from True North (Southern Illinois University Press, 2018), which won the 2017 Crab Orchard Poetry Open Prize, selected by Adrian Matejka. Her other collections include A Sweeter Water (2013), as well as two chapbooks, Garden Effigies (dancing girl press, 2015) and To Speak of Dahlias (Finishing Line Press, 2012). In 2015, she won the Crazyhorse Lynda Hull Memorial Poetry Prize, judged by Alberto Ríos. She has published poems in many journals and anthologies, most notably Quarterly West, Crab Orchard Review, Witness, Passages North, RHINO, Meridian, and the Cincinnati Review. She also has a record of publication in fiction and nonfiction, with flash fiction and lyrical essays published in journals such as Connotation Press, where she appeared as featured author for the September 2016 issue, and 4 PM Count, a journal associated with the Arts Endowment’s interagency initiative with Department of Justice’s Federal Bureau of Prisons in Yankton, South Dakota. She has received fellowships and grants from the Vermont Studio Center and the Sundress Academy for the Arts, and she has presented on contemporary women’s writing at national and regional conferences, including AWP and MMLA.

She teaches writing at Stephen F. Austin State University, where she also serves as poetry editor for Stephen F. Austin State University Press.

She teaches writing at Stephen F. Austin State University, where she also serves as poetry editor for Stephen F. Austin State University Press.