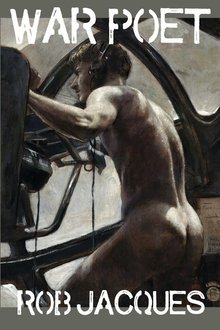

War Poet by Rob Jacques

Paperback: 122 pgs.

Publisher: Sibling Rivalry Press (2017)

Purchase: @ Sibling Rivalry Press

Review by Travis Chi Wing Lau.

In the spring semester of 2017, I co-taught with my mentor, Lance Wahlert, a course on the social and cultural histories of sex and sexuality. One of our later units addressed the forms of LGBT discrimination that underpin American institutions, such as blood donation and the military. Much of the reservations about LGBT individuals participating in public culture, specifically cultures of service like the armed forces, revolve around assumptions of not only “distraction” or “corruption” (i.e. the idea that LGBT service members are inadequate for military duty or impede the proper conduct and performance of fellow heterosexual servicemen) but also “parasitism” (i.e. the belief that LGBT individuals are merely freeloading on institutional benefits without truly giving back). Since the repeal of “don’t ask, don’t tell” (DADT) in 2010, which prevented LGBT service members from serving openly in the military, LGBT individuals have reclaimed a sense of legitimacy and pride in their sacrifices in the name of their country. Yet, as the recent Trump administrations’ attempt to bar military service by transgender troops has shown, LGBT discrimination persists despite these legal shifts toward greater equality. Jacques’ War Poet explores the stakes of this political landscape—its erotic and affective contours in the face of violence and trauma, the demands (and costs) of “serving sexless, focused on abstractions for egos, not libidos” (22).

Resisting the very sexlessness of duty, Jacques’ verses are unabashedly erotic in their representation of a soldier’s desire, how his “own body wants to make love / still sending signals to other bodies to share me, / couple with me, and in spite of dogma, survive” (22-3). Survival, Jacques makes clear, is not simply self-preservation but interdependency: fragile intimacies created between men under the difficult conditions of service. As military training deindividualizes servicemen in favor of order-based hierarchy, desire finds itself ghosted into “love-knots plaited half unaware” within the panoptic space of the ship, where

…Whispers

are overheard by invisible ears,

and a delicate, tender touch is felt

by the ship’s steel skin. Senses

aroused by endorphins are caught

by stealth electronics that detect sin (31).

Jacques’ experience as an anti-submarine warfare and cryptography specialist makes him acutely aware and familiar with ambivalences of surveillance. Watchfulness is not just for the enemy but turned inward in the naval space as a kind of policing among soldiers themselves and by the very ship itself framed in these verses as a sensate body. Soldiers are forced to inhabit the paradox of the ship itself: a space “where love has potential / to thrive in proximity to propensities that kill" (55). Sexual encounters thus become furtive endeavors that risk breaching these protocols of proper conduct, but this is what makes these acts of resistance against a “world [that] conspires against us…the U.S. Navy frowning down / (although all flesh finds it absurd) / on fraternization between enlisted / and those who have command” (33). Desiring flesh exceeds the absurdities of a repressive military culture that prefers its men “[keep] his eroticism under wraps” (48). “Encased inside all this steel, flesh exists. It breathes. It feels,” Jacques writes (50). Jacques celebrates an unspoken military heroism: a resilience, even flourishing in spite of limitation.

Jacques’ memorial poems remind me of the work of Wilfred Owen who wrote with a sentimentality that powerfully witnessed wartime loss and the fleshly consequences of pro patria mori. Like Homer’s red poppies, the bodies of fallen men, both friend and foe, scatter the volume. In the perverse circumstances of war in which soldiers are forced to ask “who will live, die,” there exists a queer solidarity between forces on different sides whose “soft bodies / don’t want to die” (86-7). Despite war’s imposition of a necessary antagonism between men, this division is ultimately artificial. At the end, there remains flesh that exists, that seeks to live. In “Washing My Enemy’s Feet,” Jacques details a tender scene of care shared between the speaker and a man he is meant to kill and is meant to kill him. The poem reveals the kinds of unexpected intimacies that emerge in the midst of war:

I hold his foot gently. I know it hurts. I try

to soak sore places of abraded skin, soothe

oozing wounds with my fingers, cleanse

his broken toes, bleeding heel and arch

as each of us peers at war through a different lens.

My hands’ touch, as close to love’s caress,

as it could be, is a soft physical submission

upon which real communication depends. (92)

Particularly tragic is the speaker’s powerful awareness of the fact that he is tending to “flesh that wants me dead” (92). For a brief moment, there is a substitution of enmity with mercy, perhaps the closest form of connection they can share in the face of “cruelties of war and worship” (93). In contrast to the more explicitly sexual charge of much of the poems in the volume, the muted eroticism here modulates the hypersexuality that too often tends to dominate narratives by and about gay men. Instead, poems like “Washing My Enemy’s Feet” affirm the belief that “steel and explosives can be softened by lusty humanity” (25).

I also read this volume as an educator, something I’m sure Jacques would appreciate as an officer-instructor at the United States Naval Academy. I have been lingering on Jacques’ injunction: “Don’t turn away! Give violent work respect!” (58). Given the ongoing debates about trigger warnings in academia and the dangers of including uncomfortable, traumatic works in our syllabi, I share Jacques’ privileging of poetry’s pedagogical value for what it may offer us in this turbulent political climate. “Poetry shows you how,” Jacques tells us, in “Teaching Poetry to Midshipmen,” a beautiful self-reflection on the act of pedagogy itself (18). Not only placing himself within the longer tradition of queer poets like Whitman and Cavafy, Jacques reminds us how poetry enfleshes experiences that may not be accessible to those who “can’t imagine bliss that doesn’t involve strife” (17). For this, I have the utmost respect.