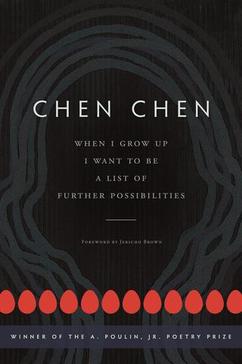

When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities by Chen Chen

Publisher: BOA Editions (2017)

Pre-order: @ BOA Editions

Review by Travis Chi Wing Lau

Chen Chen, in his interview with BOA Editions, insists that his new volume “does not promise any cathartic ‘answer’ to its many questions.” As a first-time reader of Chen’s work, I admittedly came to the volume in search of “answers,” whatever shape they might take, especially in the terrifying wake of Trump’s inauguration. I, like many other queer people of color, are left full of questions, fearful and tearful questions. And in our singular and collective askings, we struggle to grapple with traumas, old and new. But Chen forgoes the pleasure of any easy answers. What then does his work offer us?

When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities is exactly as he describes it: “a book full of love, an active, restless, ferocious love.” If, as thinkers like Patricia Hill Collins have insisted, love is indeed a political act, Chen’s book is deeply political and precisely for the reason that his “writer friend” chides him: “All you write about is being gay or Chinese.” As opposed to evacuating his poetry of identity and its discontents, Chen insists on it with a timely intensity and honesty. “I am not the heterosexual neat freak my mother raised me to be,” he writes powerfully in the opening poem of the collection. Throughout the volume, we find that identity is not neatly sorted out but an ongoing process of working through different forms of love with family members, lovers, colleagues, selves. Love, for Chen, is verbal, active.

In a series of difficult encounters between Chen and his parents, we see how selfhood, in all its “violent impossibility,” can be damaged and transformed (sometimes simultaneously) by acts of love:

I didn’t tell him I spent all night in a tree

because my mother slapped me

after I told her I might be gay.

I didn’t tell him that I hit her back

(“Race to the Tree”)

Chen is unsparing in his account of not only the violence of his parents’ rejection in both literal and metaphorical terms, but how cultural difference intersects with and shapes his queerness: “With the white boy / I liked. With him calling me ugly. With my knees on the floor. With my hands / begging for straighter teeth, lighter skin, blue eyes, green eyes, any eyes brighter than mine.” Painfully, Chen asks if it is possible to love what harms you. What Chen models for us in this volume is how to productively revisit certain pasts, however traumatic, with a tenderness, a loving that willingly suspends the convenient judgment of hindsight. As opposed to erasure or reparation of these traumas, Chen meditates on possibility of living with them: “Do I have to forgive in order to love? Or do I have to love / for forgiveness to even be possible? What do you think?” In the very refusal to give an answer in favor of lingering upon the power of an open question, Chen argues for this openness as a “form of work I’d rather not do alone.” As his readers and his witnesses, we share in this vulnerable work that is never truly finalized.

As I continue to revisit this volume, I still find myself repeating these lines from “Spell to Find Family”: “My job is to trick / myself into believing / there are new ways / to find impossible honey.” This, in so many ways, captures what is perhaps most provocative about Chen’s work. The collection, as the title itself suggests, is about “further possibilities,” about revising, reinventing, and reimagining the relational modes we currently have. If we are all tasked with being “someone ‘for’ someone else—a son, a friend, a partner, a student, a dear love,” we cannot afford to be complacent or static in the ways that we inhabit and think about those relations. Interdependence is at the heart of Chen’s writing, and if we are to survive in these troubled times, we must continue to believe that there really are new ways to find the impossible honey.

Pre-order: @ BOA Editions

Review by Travis Chi Wing Lau

Chen Chen, in his interview with BOA Editions, insists that his new volume “does not promise any cathartic ‘answer’ to its many questions.” As a first-time reader of Chen’s work, I admittedly came to the volume in search of “answers,” whatever shape they might take, especially in the terrifying wake of Trump’s inauguration. I, like many other queer people of color, are left full of questions, fearful and tearful questions. And in our singular and collective askings, we struggle to grapple with traumas, old and new. But Chen forgoes the pleasure of any easy answers. What then does his work offer us?

When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities is exactly as he describes it: “a book full of love, an active, restless, ferocious love.” If, as thinkers like Patricia Hill Collins have insisted, love is indeed a political act, Chen’s book is deeply political and precisely for the reason that his “writer friend” chides him: “All you write about is being gay or Chinese.” As opposed to evacuating his poetry of identity and its discontents, Chen insists on it with a timely intensity and honesty. “I am not the heterosexual neat freak my mother raised me to be,” he writes powerfully in the opening poem of the collection. Throughout the volume, we find that identity is not neatly sorted out but an ongoing process of working through different forms of love with family members, lovers, colleagues, selves. Love, for Chen, is verbal, active.

In a series of difficult encounters between Chen and his parents, we see how selfhood, in all its “violent impossibility,” can be damaged and transformed (sometimes simultaneously) by acts of love:

I didn’t tell him I spent all night in a tree

because my mother slapped me

after I told her I might be gay.

I didn’t tell him that I hit her back

(“Race to the Tree”)

Chen is unsparing in his account of not only the violence of his parents’ rejection in both literal and metaphorical terms, but how cultural difference intersects with and shapes his queerness: “With the white boy / I liked. With him calling me ugly. With my knees on the floor. With my hands / begging for straighter teeth, lighter skin, blue eyes, green eyes, any eyes brighter than mine.” Painfully, Chen asks if it is possible to love what harms you. What Chen models for us in this volume is how to productively revisit certain pasts, however traumatic, with a tenderness, a loving that willingly suspends the convenient judgment of hindsight. As opposed to erasure or reparation of these traumas, Chen meditates on possibility of living with them: “Do I have to forgive in order to love? Or do I have to love / for forgiveness to even be possible? What do you think?” In the very refusal to give an answer in favor of lingering upon the power of an open question, Chen argues for this openness as a “form of work I’d rather not do alone.” As his readers and his witnesses, we share in this vulnerable work that is never truly finalized.

As I continue to revisit this volume, I still find myself repeating these lines from “Spell to Find Family”: “My job is to trick / myself into believing / there are new ways / to find impossible honey.” This, in so many ways, captures what is perhaps most provocative about Chen’s work. The collection, as the title itself suggests, is about “further possibilities,” about revising, reinventing, and reimagining the relational modes we currently have. If we are all tasked with being “someone ‘for’ someone else—a son, a friend, a partner, a student, a dear love,” we cannot afford to be complacent or static in the ways that we inhabit and think about those relations. Interdependence is at the heart of Chen’s writing, and if we are to survive in these troubled times, we must continue to believe that there really are new ways to find the impossible honey.

Chen Chen was born in Xiamen, China, and grew up in Massachusetts. His debut poetry collection, When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities, won the A. Poulin, Jr. Poetry Prize. His work has appeared in two chapbooks and in such publications as Poetry, Gulf Coast, Indiana Review, Best of the Net, and The Best American Poetry. He is the recipient of fellowships from Kundiman, the Saltonstall Foundation, and Lambda Literary. He earned his BA at Hampshire College and his MFA at Syracuse University. He lives in Lubbock, Texas, where he is pursuing a PhD in English and Creative Writing at Texas Tech University. For more about Chen Chen, visit www.chenchenwrites.com.